A Foolish Proposal

On the purpose of persuasion, Proclamation 95, and the difference between extreme and extremist.

Yesterday I made a proposal. It was probably very foolish. I admit as much.

Before I show it to you, I’d like to give you a couple scenarios.

The Reframe is supported financially by about 5% of readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor.

Click the buttons for details.

SCENARIO 1: Imagine we’re driving on a highway in a car, you and me. Let’s say we’re on a road trip to a concert. You’re at the wheel. We’re going 70 mph on a pleasant sunny spring day, and I have a suggestion for you. I want you to slam on the brakes and turn the wheel as hard as you can and drive us into the ditch.

My reasoning is that 70 mph is far too fast for a human being to go, and therefore you are being hugely irresponsible right now. You aren’t exactly persuaded by this. You point out that while, yes, under normal conditions, 70 mph would be an unsafe speed for humans, the fact that we are currently in a car actually changes the context significantly, and means that we can, provided we don’t do anything drastic, safely travel at 70 mph indefinitely. I am unpersuaded by you, and I tell you that I don’t believe there is any such thing as a “car,” and that you would never let for example your child ride their scooter at such speeds.

You are befuddled by this (in no small part because earlier in the day, when I drove, I was going 85 mph), but you don’t see much more point in arguing about whether or not cars exist. You refuse to enact my plan, because doing so would create a very strong possibility that we will flip the car and have a terrible accident, and you do not want to have a terrible accident. I really want to drive us into the ditch, though, so I try to wrest the wheel away from you.

Now, imagine there are two passengers in the back. Let’s call them Tab and Rhonda because those are their names according to me. Tab and Rhonda are understandably shocked and distressed by my actions, and also do whatever they can to prevent me from risking all our lives.

You and Tab and Rhonda are all fighting me, even though all of you would probably agree that fighting isn’t generally good, and you’d rather not do it, all things being equal.

But you all fight me anyway, because all things are not equal, and what I want to do is extreme, and I am an extremist, because I want to endanger us all for no good reason, and I am unpersuadable about obvious matters. So you are going to have to persuade me a different way—by fighting me—because otherwise catastrophe will be inevitable, and time is short.

OK, let’s reset the scenario.

SCENARIO 2: You’re at the wheel, it’s a pleasant day, 70 mph. Tab and Rhonda are in the back, playing cribbage. I don’t know why. They’re weird.

Now, let’s say that ahead we see a massive explosion. Five gas tankers have crashed into five toxic waste tankers. Ahead the air is an unbreathable inferno. The road is entirely blockaded by wreckage.

I want you to slam on the brakes, my point being that an unbreathable inferno is dangerous for human beings, who tend to need to breathe, and that cars that try to drive through fiery wreckage tend to turn into fiery wreckage. You are not persuaded, pointing out that 70 mph is a perfectly safe speed for a car, and that in the case of collision, you and I have the best of airbag technology to protect us. Rather urgently, I make the case that the car’s mechanical capacities have nothing to do with my point … but you refuse to be persuaded, and point out that stopping suddenly on a highway is hugely dangerous, not to mention in clear violation of the rules of the road.

You tell me you don’t believe that the crash that is rapidly drawing near is real, and even if it is, you don’t see any evidence that it was caused by us going toward it at 70 mph. I am befuddled by this (in no small part because crashing into another car is also in clear violation of the rules of the road), but I don’t see much more point in arguing about whether or not there is wreckage ahead. I demand an immediate stop.

From the back seat, Tab is shocked by my extreme suggestion. He agrees that the inferno is a problem, but insists we use the existing roads and existing traffic rules to solve that problem, and that breaking those rules would create dangerous precedents in case the next driver of our car is the sort of maniac who just slams on the brakes and drives into ditches for no reason.

Rhonda is concerned about the inferno, but she doesn’t want to be late for the concert, and she’s not really comfortable with arguments; she thinks we all stay safer when we’re unified.

We get nearer to the wreckage, so close that we can feel the flames, so close that there would be no way to stop the car in time to save us, so I try to grab the steering wheel and drive us into the ditch, and you and Tab fight to stop me, while Rhonda decides that it’s safer to stay neutral.

It’s the exact same scenario, except for the reality of the impending catastrophe.

I am still grabbing the wheel from the passenger seat to steer us into the ditch. My action is still just as extreme. But now I am the only person in the car who isn’t an extremist, because I recognize an extreme reality. And time is short, and getting shorter.

You are extremist, because you want to choose an inevitable catastrophe over a smaller risk, and are unpersuadable about obvious matters, and Tab and Rhonda are extremists, because they would rather drive into certain doom than break rules or take any immediate necessary action that would be unthinkable in calmer times.

So what’s my point?

Last week I told parables, and in honor of that art form, I stayed cagey about what my stories meant. This time, though, I think I’ll just give it to you straight.

What I’m saying is that, while the two often intersect, there is a difference between extreme and extremism, and the difference depends on circumstances, so knowing the difference depends on observing certain things about reality.

What I’m saying is that sometimes doing an extreme thing is extremist, and sometimes not doing an extreme thing is extremist, and the difference depends on circumstances, on recognizing whether or not an emergency is occurring, and what the immediacy of the emergency is, and who is at risk.

I’m also saying that there is a purpose to persuasion, or at least there should be, or perhaps that persuasion without purpose is pointless.

Sometimes stopping extremism requires persuasion, but sometimes it requires picking a fight, and recognizing which is needed in the moment depends on understanding the immediacy of the emergency, and the stakes of not acting.

Finally, I’m saying that the longer you delay in opposing extremist behavior and intention, the more extreme the reality of your danger becomes, and so the actions needed to avoid extremist catastrophe tend to become more extreme and more dangerous over time, not less—so it seems to me we’d do well to find an extreme response to catastrophe earlier rather than later.

Anyway, I’m thinking about extremism because the Republican-controlled House of Representatives is trying to strong-arm the president into giving it what it wants, which is to cut funds to people in desperate need, like unhoused veterans, for example, and people who are food insecure. And they want some other cartoonishly cruel cuts, as well. If they don’t get what they want, they promise to default on our national debt, which will crash the economy, which will create more suffering for more at-risk people, and they then promise to blame all this on the president. If they do get what they want, the observable history of Republican action and intention leaves us with little reason to hope they won’t just do all that, anyway, and there’s not much to be done about it, because they are the people in charge of making them pay any consequence for what they’re doing.

Also, the Supreme Court has been captured by a bunch of supremacist authoritarians whose conservative members all appear to be on the take from billionaires with supremacist agendas to which all the bribed judges appear to be entirely aligned. It’s not really provable that these judges are dismantling the legal framework upon which our nation’s attempt at a modern pluralistic society is based because they’re getting paid in luxury vacations for themselves and real estate deals for their family members, but it’s clear that they are for sure doing both of those things, and that there is no way to make them pay the slightest consequence, because the people in charge of doing that are the same supremacist Republicans who are threatening to crash the economy, and they find a corrupt supremacist court very useful in promoting supremacy, which is what they want to do.

And every day there’s a gun massacre or two, because our culture has been optimized for gun massacres, and you’ll never guess who the people are with the power to block any attempt at remedy. Yep! Same people! And they do indeed block any attempt at remedy, because for them a world of easy and plentiful massacres is the price society has to pay for freedom, by which they mean not the right of a person to live in a society without the constant threat of massacre, but the right of anybody to quickly and easily buy as many massacre weapons as they want.

And there’s an active attempt at genocide of trans people, and a real push to demolish things like democratic elections and the bodily autonomy of women and libraries and public schools, because all of these things suit the agenda of supremacist autocracy, just as much as corrupt judges and the ability of angry men to purchase massacre weapons do.

And the last President, who was a supremacist authoritarian, is running for president again, and is almost certainly going to be the candidate of his supremacist authoritarian Republican party next year, unless somebody else can manage to promise to be more authoritarian and more supremacist, but the last President is promising to be very authoritarian and supremacist, and it’s pretty clear that as long as one of our two parties is an authoritarian supremacist one, our democracy is going to play Russian roulette with at least half the chambers loaded every two years.

And hovering over all this is a climate catastrophe whose first effects are already here, whose endgame is growing closer and closer, and which threatens to make our only planet an unbreathable inferno for billions of people—and every remedy we might pursue is opposed by the same people who are making sure that massacres happen every day, and that our courts are captured and corrupt; the same people who are threatening to crash the economy in order to make the president harm people who are already suffering, and who insist that any attempt to avoid the unbreathable inferno would be far too extreme to pursue.

So all that is going on.

Seems like a lot of emergencies, and it seems like the urgency is growing.

Seems like the stakes are high.

Anyway, I was going to tell you about my foolish proposal.

But first, let’s talk about Abe.

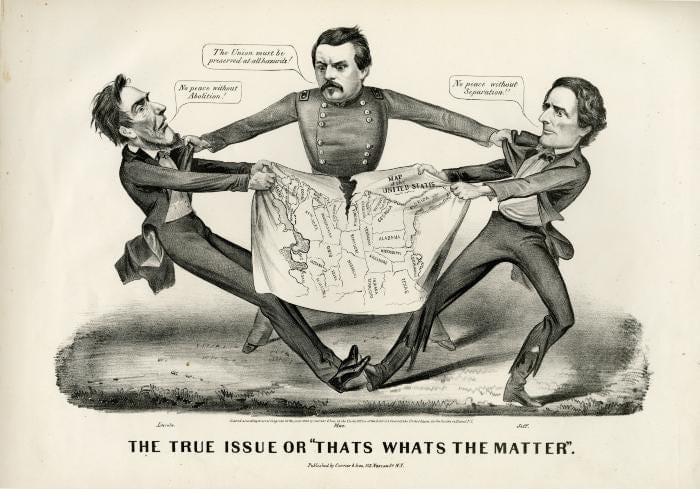

OK, so there was once this fellow named Abe, and he was a president of the United States, which is a country made up of a union of states you might have heard of, and he is largely credited with saving that union, because when extremist aggressors arose to destroy it in order to preserve their own supremacy, he fought them to prevent that destruction. The fight is known as The Civil War, though I prefer to call it The Failed War to Preserve Slavery. It just seems a more specific and honest name.

I don’t think the fight was good, by the way. I’m not pro-fight. But the fight had become necessary, and so I’m glad that Abe did the necessary thing, even as I wish that he hadn’t had to do it.

We should be careful about drawing direct parallels. Every age has its differences, and Abe faced a different set of emergencies than we have now. There were actual armies of supremacist extremists in the field, for one thing, and there had been actual declarations of secession. We should probably hope to avoid allowing our supremacist extremists from getting to that point, though I do notice that more and more supremacists these days are engaged in more and more freelance-type massacres against the sort of people that supremacist propagandists like Fox News tell them are problems to be solved, so maybe these days the militias are just less well-regulated, and today’s secessionists have simply decided that their predecessors’ mistake was announcing their secession, after which they could no longer work from the inside to sabotage the nation they intended to overthrow.

But anyway: I was talking about Abe. He saved the Union because he was willing to fight supremacist extremists for it. That’s the story. Maybe you saw one of the many movies. Maybe you read one of the many books. Maybe you visited the memorial with the statue. You should, if you get the chance. It’s quite a sight; grave and solemn and majestic.

Again, saving the Union meant being willing to fight the supremacist extremists who were willing to fight to destroy it. This just seems like a simple observation of something I think you have to implicitly believe, if you are also going to believe the received knowledge that Abe saved the Union—which I do believe, by the way.

Anyway, there’s something Abe did during The Failed War to Preserve Slavery, which was celebrated in his day as one of the greatest things any president has ever done with their power, and which is still celebrated in those terms today.

He issued a presidential proclamation—Proclamation 95, which emancipated all the enslaved people within the states that were (in the interests of their supremacy) fighting to destroy the union. Proclamation 95 was a tactical document in many ways, designed more to destabilize the traitors’ ability to wage war than to end the institution of human slavery. It was designed to weaken the opposing armies, and to give Abe and the armies he commanded space to win the literal fight before them—the thing that was immediate and urgent.

But it was also designed to give Abe leverage in passing an amendment to the Constitution that would abolish many forms of slavery permanently—something that would have been impossible to do if he were not fighting supremacists, and beating them, which is something that would have been far harder to do if he had not issued Proclamation 95.

Now here’s the thing about Proclamation 95: it was extreme. It wasn’t quite as extreme as sending armies into the field to meet the extremists who were trying to destroy the country, but it was extreme. It was extremely extreme.

It’s called The Emancipation Proclamation. You’ve heard of it.

It was considered a massive overreach of executive power. Lawyers questioned its legality. Critics pointed out that it would almost certainly be overturned by the courts. Opponents on both sides of the conflict considered it tyranny, and called Abe a despot for issuing it. Abe was eventually murdered at least in part because of it.

Another thing: the critics weren’t all wrong about Proclamation 95.

It had a very carefully prepared legal rationale, but it was most likely against the rules. It was a massive overreach of executive power. It probably would have been overturned by the courts. And all of the things that are true of Proclamation 95 would also be true of any sort of horrible and abusive extremist executive order or proclamation that any despotic and authoritarian tyrant might make, by the way, like targeting a marginalized community for genocidal harm.

Yet we celebrate it today. I think this is because we recognize the difference between extreme and extremist. It would be easy to frame it as tyrannical, because it was exactly the same as a tyrant’s order, save one tiny exception, which is that it wasn’t abusive or harmful or tyrannical, but rather oppositional to abuse and harm and tyranny. It didn’t create a catastrophic situation, but rather fought to end one, and to prevent a worse one.

One other thing about Proclamation 95 and The Failed War To Preserve Slavery: the conflict it addressed wasn’t a new conflict when Abe showed up. It had been a hugely divisive issue for fourscore and seven years before that. Slavery had been an extremist thing all along, but it never faced significant enough opposition during those years to prevent it from reaching an inevitable violent catastrophe. The violent catastrophe was inevitable because, while supremacist human enslavement was an unsustainable extremist institution, the rules had been set up so that ending it without the permission of supremacist extremists would be against the rules, which meant that avoiding the catastrophe was going to require something extreme, and when it came to the sort of extreme act that would have been needed in order to avoid the extremist catastrophe, nobody was able or willing (or both) to do it.

It was an inevitable catastrophe that extremely wealthy and respectable supremacist extremists drove the nation toward, year after year, at a steady speed of 365 days per year, and nobody ever successfully grappled with them for the wheel. Everyone instead operated within what was realistic and practical and achievable, and not hitting the brakes too suddenly, and staying out of the ditch. By the time Abe showed up, the catastrophe had already become unavoidable. By the time Abe hit the scene, fighting the supremacists meant fighting pitched battles against armies in the field.

Sometimes I wonder what the story might have been, if somebody willing to fight supremacists for the union (which means fighting the supremacist extremists determined to destroy it) had showed up before it got to that point, and had been willing to take extreme and dangerous but necessary action to avoid an obviously impending catastrophe.

I think it would still have involved breaking the rules, just as Abe did. It would still have required something extreme yet not extremist. And maybe it would have been something less extreme than sending armies into the field. Maybe there would have been no pitched battles. Maybe hundreds of thousands of lives would have been saved.

Probably not. What do I know? Not much. Honestly, I really don’t. I’m a fool, mostly.

But I do wonder.

Wondering often results in me making foolish proposals about our inevitable impending catastrophes, and the supremacist extremists currently at our national wheel.

OK.

Enough throat-clearing.

Here is the foolish proposal I made yesterday.

Biden should issue an EO stating that the Supreme Court is illegitimate and name 9 appointees, including Sotomayor, Brown Jackson, Kagan, and 6 others.

Wow! A.R. Moxon, coming in hot!

This proposal was in response to new documents showing that Jane Roberts, the wife of Chief Justice John Roberts, has received $10.3 million in commissions from elite law firms with business before the Supreme Court, and this matters because Jane Roberts is the wife of the Chief Justice of that court, and he has recently declared his unwillingness to investigate similar conflicts of interest and cases of outright corruption that have come to light involving other conservative members of his court, and that’s a problem, because looking into those things is something that our rules leave largely up to him.

So, in recognition that our rules prevent any consequence for grotesque corruption of our courts, I made my proposal: recognized, the court has made itself illegitimate through corruption and supremacist capture; recognized, our rules provide no path to do anything about it; therefore, it is necessary to dissolve the court by executive order.

This proposal struck many people as foolish, and exasperated a lot of people for that reason—some of whom I talked to, and some of whom I blocked1, but anyway you can read the various bits of back-and-forth if you want to, by clicking the link up there at the top.

Look, I get it.

I know my proposal is foolish. I know it’s unrealistic and unachievable and impractical.

You may be a lawyer, which I am not. You may have a lot more awareness of the operative political procedures and protocol than me, which wouldn’t be a hard mark for you to hit. You may be a political tactician, in which case I am sorry for whoever has to sit by you at parties, but I believe you when you tell me that you know better than me about what is realistic and practical and achievable in the current political environment.

My foolish proposal is definitely extreme. It would be hugely disruptive and dangerous. It’s no doubt against the rules, though I imagine that one could probably make a carefully worded legal rationale for it. We’ve made carefully worded legal rationales before for extreme and extremist things that are against the rules, like our unlawful torture program—but that’s enough about Ron DeSantis for today.

I have good news, by the way, if my foolish proposal bothers you. There is no way it’s ever going to happen. Joseph Jumping Biden isn’t going to even consider such a thing for a moment. Steady-As-She-Goes Joe would take one look at my idea, flash his half moon of brilliant white choppers in incredulous amusement, and tell me that my idea is some real horse-pucky, Jack, nothing but a bunch of real shady possum bingo, and I’m not kidding.

He’s probably right, too. I’m not mad at him for not doing that specific thing.

My foolish proposal isn’t going to happen.

So why would I make such a foolish proposal?

Because I’m trying to persuade, while there’s still time to persuade.

I’m trying to convince people that there is a difference between extreme and extremist, and to understand why seeing the difference is crucial. I’m trying to convince people to choose a lesser danger and a smaller chance of violence, before autocratic supremacists pursuing inevitable catastrophe choose maximum danger and violence for us.

I’m not so much excited about creating energy for my specific (foolish) proposal, as I am about a general understanding that we are now in an extreme reality, and we don’t get to choose to not be in one, because the catastrophes are imminent. It’s not so much that I want my foolish proposal, but that I recognize that we are probably going to need a foolish proposal, and the longer we wait, the more extreme that foolish proposal is probably going to need to be. Since the methodology and power for deciding on the rules have been captured, we are now facing a range of impending catastrophes that are going to become more and more inevitable if we focus only on what is realistic and practical and achievable, or if we are only comfortable with the sorts of remedies that would be healthy in times of comfort.

I’ll go further. I’m quite certain that my foolish proposal would be the wrong one. I’d think we’d need somebody far smarter than me (not difficult) to figure out what the best foolish proposal is to pursue, and the best tactics by which to pursue it.

But first, we need to understand that extreme action is needed, and that is the thing I’m trying to put into the atmosphere.

I don’t really think that the best purpose of persuasion is to argue over points of observable reality with people who refuse to observe them, or to argue about the various remedies that are possible within our present situation, with people who refuse to observe the problems we presently face. I think the best purpose of persuasion is to imagine things that, given our present situation, are not possible but are necessary, and get other people to see the possibility and the necessity as well—to change the scope of what is possible.

Because look—our Supreme Court, which decides on the rules, has been captured by a supremacist authoritarian movement and corrupted by plutocrats aligned with that movement’s practical and rhetorical goals, and so has one of our two major political parties, which means the rules for doing something about a corrupt and captured illegitimate court are largely in the hands of the same people who want the court to be and stay captured, corrupt, and illegitimate. And I know not everyone agrees with me about that, but not everyone agrees that The War to Preserve Slavery was fought to preserve slavery, so at some point we have to understand that any persuasion with any purpose has to involve interacting with people willing to recognize reality.

I don’t think it’s sustainable for us to have a corrupted and illegitimate high court, captured by authoritarian supremacy, working to demolish the foundations of our attempt at a pluralistic modern society for much longer.

I don’t think it’s sustainable for us to ignore climate catastrophe, or to entertain an authoritarian supremacist party, or the ways they are pursuing sabotage and genocide and disenfranchisement and genocide of marginalized communities for much longer.

I think these catastrophes are in large part already here, especially for people already targeted by them, and are for the rest of us becoming increasingly inevitable, and I think we are going to need to shelve our comfort in favor of extreme (but not extremist) remedy, hopefully before the violence that supremacist extremists now threaten becomes too inevitable to avoid.

So I made my foolish proposal—the one that suggests that it would actually uphold the law and foster stability to dissolve a court made illegitimate by extremist capture and corruption, even while it recognizes that dissolving a court is extreme, and also impractical, and also dangerous, and also, at least for now, impossible.

What I’m trying to do in my foolish way is to get us to focus on things we already know about the difference between extreme and extremist, which means that we will need to acknowledge that extreme is not something we should avoid in times of impending catastrophes, but something we should seek, if we wish to avoid the sort of catastrophic fate that extremist supremacists seem determined to create.

For long years before Proclamation 95, there were proposals and demands and arguments to abolish slavery in a sweeping way. I don’t think that any abolitionists proposed the Emancipation Proclamation, because that document was situational to those exact times, but they did agitate for abolition of slavery, which was something that according to the rules required the permission of people who opposed abolition. This wasn’t a realistic, or practical, or achievable proposal—it was only a necessary one. Eventually, the catastrophe came so near that the necessity became inevitable, at a time when what had become necessary to avoid it had become as extreme and dangerous as possible.

But it was always necessary, and never achievable, or practical.

It was, in fact, impossible.

It was a foolish proposal.

Many necessary things start that way.

Today, I dare hope that we can make ourselves comfortable with foolish proposals.

Thank you for reading The Reframe. This post is public so feel free to share it.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. When he was seventeen, it was a very good year.

The blocking depended not so much on whether or not they may have had a point, but on whether or not they were being obstreperous dicks, because frankly there are enough smart people out there to keep me honest about my foolish proposals who aren’t obstreperous dicks, and I just don’t have any patience for obstreperous dicks anymore. ↩

Comments ()