A More Redeeming Violence

Enjoy this Very Fine Excerpt from Very Fine People - about the sort of violence that make so many of us feel safe, and the orienting spirit that such violence reveals about a society that enacts it.

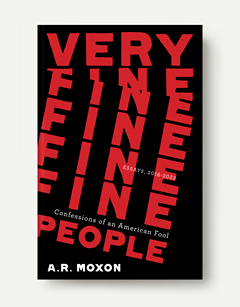

I'd like to publish an excerpt today from my upcoming book, Very Fine People: Confessions of an American Fool. Typically the savvy time to do this would be when I have pre-order links live so I could drive sales, but a) as you've probably figured out by now, I'm not very savvy; and b) the last essay I wrote was the one that used Spike Lee's masterpiece Do the Right Thing as an entry-point to the idea that fascism often expands by offering a violence that the fascists frame as safety, so if we are anti-fascist people we'd do well to explore what sorts of violence makes us feel safe, and why safety is what we feel when we hear about it, why fear is what we feel when we hear about the prospect of its cease. And it just so happens that this essay speaks very well to what I mean by that.

The essay is called "Redeems" and it is a part of a series called "Bubbles," which I wrote in the first half of 2017, and which some of you might have read back then, and which others of you haven't, and I love you very much either way.

The series posits the idea that all human beings are not products or objects, but living art carrying a worth that is intrinsic, indestructible, and unsurpassable. Then it posits the idea of spirit as the thing we need to change in my country (which is the United States)—"spirit" meaning not ghosts and woo-woo stuff, but just the way collective beliefs take on real-world effects and momentum, and set the stage for what is possible and what isn't. It then suggests that the reason we need to change our national spirit is because our current national spirit is the spirit that founded our country, a spirit founded on terrible foundational lies, a spirit that wants and enacts genocide and slavery.

And then I lay out the foundational lies.

The first foundational lie is that we aren't related to one another; that human society is marked not by connection but by separation.

The second foundational lie is that life must be earned; that some people have earned life and that others have not, and that because those who have not earned life have not earned it, they do not deserve life or the things that bring life.

The third foundational lie is about violence that makes you feel safe. No—not you. Me. Violence that makes me feel safe, when it does—because the idea of "Bubbles" is that a bubble is a mirror that doesn't let one see oneself; hides one's own motives and beliefs from oneself, which suggests that the way to pop a bubble is from within. So while you might find yourself here, in these cases I try to always remember to first say I.

So here's me, coming to you from the faraway and distant land of 2017:

Today's essay is from a collection called Very Fine People: Confessions of an American Fool. It's coming out in June, and my readership is helping me do that. If you want the details on how you can get in on that and get a signed copy and my thanks in the acknowledgements section of the book, click this link.

We’ve convinced our society that we aren’t related to one another.

We’ve convinced our society that life is something you have to earn.

We’re close to making genocide inevitable now.

What’s next?

Next, we must convince our society of the third foundational lie: that violence redeems.

This is not particularly hard to do. We humans are good at violence. It’s hardwired right into our amygdalae. It’s the distillation of the plot of many of our most popular movies. If you hit me, I hit you harder. If you hit back harder still, I hit you back hardest of all. Eventually I will hit you so hard you can’t hit anymore, and then the problem of you will be solved. If they bring a knife, you bring a gun. They send one of yours to the hospital, you send one of theirs to the morgue. That’s the Chicago way, and that’s how you get Capone, yipee ki yay, motherfucker. Roll credits.

This is order’s narrative: There are villains. You kill villains, and order is restored. You kill the boss villain at the end of video games after killing all the sub-villains. The hero kills the boss villain at the end of movies after killing all the sub-villains. Order is restored.

One important part of order’s narrative is that the hero doesn’t just show up and start violencing all over the place until the place is full of violence. The hero ends the violence that somebody else started, with redeeming violence of their own, which escalates until at last it has cleansed the narrative of all sources of bad violence. So we see that violence can’t merely be the solution in order’s narrative; it also has to be the problem. Violence can’t merely be very very good, it also must be very very bad. This is why we must first determine that we aren’t all related, and that life must be earned. You need only look at who is doing the violence to know if it is good violence or bad violence. People who haven’t earned life do bad violence that could never be good, and people who have earned life do good violence that could never be bad.

“They” do bad violence to us. “We” do good violence to end it.

Certain conclusions present themselves.

If they keep doing bad violence after our good violence, it is because we didn’t do enough good violence previously. The solution becomes obvious: we must do more good violence at them—harder violence, or more-widely applied, or more brutal, or all three. The violence isn’t just good; it redeems. It is the perfected instrument for restoring bad things to goodness. We know our violence is good, because we do it. We revere it. We have parades and whatnot. Their violence is bad violence. We know it is bad, because they do it. We hate it. We will eradicate it from the face of the planet, like we did in World War I, which ended all war, and World War II, in which we stopped evil in its tracks forever, and the Cold War, in which we permanently stabilized the world through proxy violence in countries other than that of our primary adversary, and also the War on Drugs, which stopped the drug epidemic, and the War on Terror, which has stopped terrorism forever. . . .

Let me push back against myself on behalf of those of you who might imagine I am losing my marbles. What the hell am I suggesting, exactly? That we shouldn’t have fought Hitler in WWII? That violence is never appropriate? That we oughtn’t to revere those who served and suffered and even died in our armed conflicts? That we should just let terrorists go on with their heinous deeds, consequence-free? What if we were all speaking German right now, huh, what then? Or, how about this: What if there were some maniac in my house ready to kill my kids? What if my wife were attacked? What if I was being beheaded by terrorists? I’d feel a bit differently then, wouldn’t I?

Well . . . yes.

I suppose I would feel differently about violence, if that were happening. Those things sound horrific. So let me say, right here and now, that if some maniac were getting ready to murder my children, I would welcome a weapon for the chance to stop that maniac, or the sudden appearance of somebody armed with both a weapon and the intention to stop that maniac. That would be just the ticket in that situation. I would not turn it down. I would also like to take this opportunity to express my opinion that Hitler was bad. It is good that we stopped him, and it is to the credit of our country and our allies and those who bravely served that we did stop him. Glad to finally get that off my chest. I’ll say it again: Hitler was really bad. Good that we stopped him. Let me also say that people who put their physical well-being and their very lives at risk in service of others exhibit a bravery that I believe deserves our wonder and our respect.

I would also observe that bravery isn’t what receives our first respect, as a society.

We seem to be more into the redemptive power of violence.

It’s worth remembering that we rarely set ourselves in opposition to things that are evil in and of themselves; rather we find ourselves dealing with some good thing that has been elevated above its proper place. The key question, usually, is one of priority between good things. For example, order and prosperity and hard work are not bad, but they become corrupted when they are made more important than the unsurpassable worth inherent to human beings, who are art. Is it like this with violence? Can we imagine times when violence becomes necessary to prevent some terrible abuse from taking place?

I think we can. At least we might name something that can be good, within certain contexts where violence has been made inevitable by abusive intent.

Let’s talk about physical bravery.

Physical bravery can be very good.

It’s 2017 now. Recently in the news there was a story about a man, captured by our foundational lies, who boarded a train with a knife. There he saw a woman with whom he knew he shared no relation, because her outfit marked her as a Muslim. Because she was a Muslim, he believed she represented bad violence, and had therefore not earned life. He set about to make her understand, at the foundational level of terror, that she had not earned life. He made it clear to everyone nearby that he intended to relive her of the life he had decided she had not earned. The man with the knife had decided to make violence inevitable. Three brave men stepped in to stop him, and this act created a violent altercation between them and him, instead of between her and him. Ricky John Best, 53, died in the train car. Taliesin Myrddin Namkai Meche, 23, succumbed to his wounds in the hospital. A third man, Micah David-Cole Fletcher, 21, was injured and hospitalized but survived. I think it was good that those men acted to protect that woman. I think it was very good. I think it is appropriate to honor such acts of physical bravery, and the sacrifice that frequently accompanies them.

The question is not whether physical bravery is good. It very obviously can be very good, and even heroic. And certain acts of physical bravery will engage with violent intent, which will create an inevitable violent outcome, in order to try to change the nature of the violence, and the outcome. I don’t know a non-violent way to stop a hypothetical maniac from hypothetically killing my children once he’s in my house with murderous intent, and I very much do not want my children to be killed, hypothetically or otherwise. So it seems violence has a very specific appropriate scope when properly applied within an orientation aligned toward justice. It addresses a specific and immediate problem, which is frequently if not always unexpected. It has a temporary duration and a clear goal with a clear end point. It is most frequently done on the behalf of others. It is not instigated. And, crucially, it is done because without the application of violence, some other violence will inevitably occur, and no power better than violence is available in the immediate moment to counter it. But violence always strikes me as a tragedy or at least the result of a lack of imagination. Despite previous hypotheticals involving home-invasion maniacs, some other solution is almost always available.

Even to the extent that it is necessary, violence is only ever a fix. It is never a solution. It is the weakest power. If any other power is available to fix the immediate problem, that power is the better power. But the compass decides the navigation, and the navigation sets the course, the course decides the path, and the path determines the destination. And if our compass tells us that we are not related, it will also tell us that other people do not matter. If it tells us life is something that some people have not earned, it will also tell us it is their own fault that they do not matter. Little wonder, then, with such a compass, that our course becomes a preemptively violent one. Little wonder, then, that violence is so often our first solution, or even our only solution.

When violence is posited as a natural solution, it has been inappropriately elevated. When it becomes the preferred solution, then the society that prefers it has oriented itself to violence, a compass setting that states “we will use violence as a first choice to achieve our objectives.” It is an orientation toward violence that says that violence is the strongest power, not the weakest, the first resort, not the last. It’s an orientation toward violence that believes violence redeems, that creates a preference for violence as the prime mover of justice, or even a conflation of violence and justice as being interchangeable. It’s an orientation that can make a non-violent response seem fearfully foolish. It’s an orientation that makes violence not only likely, not only preferred, but inevitable.

As I mentioned earlier, those who demonstrate physical bravery on behalf of others deserve our wonder and our respect. I also think they deserve more: a deep examination, on our parts, prior to any decision that requires them to exhibit that bravery; and after, an interrogation of our motives and objectives behind decisions—such as the decision to go to war, such as the decision to create a world that permits people to live in abject poverty—that made this violence so apparently necessary; and a thorough inquiry after the fact, as to whether those motives were honored and those objectives achieved. Exactly why did we put brave people into a desperate risk? Did we honor their astounding selflessness by setting our goals to appropriate ends? Did we secure those ends? Are we willing now to sacrifice and pay the price to provide for those brave people who acted on our behalf, and ensure those ends are maintained? In what way was the violence they were compelled to enact, however admirably brave it might have been, a sign of some turn we missed on our road, some collective failure to select justice at some earlier point? What cost might we now have to bear, what changes might we make to our foundational beliefs and institutions, to honor their brave sacrifice by reorganizing our society in such a way as to make such sacrifices unnecessary in the future?

When violence is my orientation, I no longer have to ask those questions. I don’t have to worry about motive or objective—the violence itself represents purity of motive and objective in and of itself. And I no longer have to concern myself with the aftermath, because if I believe that violence redeems, then the aftermath to violence will always be more violence, until we at last come to the end of violence, an end we will only reach when those who have not earned life no longer exist. I think this, incidentally, is why so many who claim to revere the military also support policies that abandon veterans. If I am a violence-oriented person, then honor was never the point: violence was. When dealers of violence no longer can provide the violence I need them to enact in order to make me feel safe, they will have reached the end of my reverence for them, and can be discarded. I might point to their neglect as a rationale for not taking care of other neglected people who aren’t veterans when we haven’t yet taken care of the veterans, but I certainly won’t support actually caring for them. Taking care of our veterans isn’t profitable, after all, and life is something you must earn.

My orientation toward violence advises me that the way to stop the threat of maniacs entering my house to kill my children is to identify all the maniacs and kill them before they ever enter my house—or, failing that, to always be ready at a moment’s notice to kill any hypothetical maniac—to assume that it is my job to be constantly watchful for maniacs and ready to deal my perfected violence upon them at any sudden adrenalized moment. This is an orientation toward violence that puts my family in greater danger, not less, because the presence of firearms is strongly correlated with firearm-related death, and the person most likely to kill you is a family member, but I will still prepare myself for violence that endangers my family in the name of keeping my family safe, because I am oriented toward violence, which means that I believe violence is the only thing that could ever save my family from violence.

The way to end crime is to lock up or kill all the criminals, by my definition of criminal.

And the way to end terrorism is to kill all the terrorists, by my definition of terrorist.

And the answer to those who have not earned life is that they have earned death.

And somebody ought to deliver that death.

And I am somebody.

So, hey, let’s kill all the Muslim extremist terrorists. Right? So we attack a place where some of the terrorists are. We also attack a place where the terrorists aren’t, but which seems like the sort of place terrorists might go. The terrorists see that we are now there. They meet us there and begin to attack. We attack back. We attack with the largest and most expensive and powerful military the world has ever seen. We dig in. They kill us. We kill back harder. Homes are reduced to rubble. Hundreds of thousands of unaffiliated people—spouses, children, parents, siblings, neighbors, friends—die in all this carnage.

They keep killing us.

We decide our mistake was not killing hard enough. We surge.

At some point, it becomes natural for us to be at war.

We start to praise our bombs on television for their beauty and size and sophistication. We build remote-controlled airplanes that can deliver death from heights undetectable to the naked eye, and they deliver death and destruction until normal people on the other side of the planet begin to live in terror of a clear blue sky, and the flag that is painted on those aircraft—red, white, and blue—becomes for them a symbol of terror.

There is not less violence now than when we started. There is more.

There are not fewer terrorists now than when we started. There are more.

We have eagerly joined with the terrorist in bringing terror to the innocent. And still we, captured in our belief of violence’s redeeming strength, think the answer is that we have not yet been fierce enough in our prosecution of good violence—obviously so, because bad violence still exists. Many of us think the problem is that we haven’t yet cast a wide enough net of violence. Perhaps we need to kill different people, in some new countries. Perhaps we need to suspect more people abroad to see if they need death. Perhaps we need to start suspecting more people here at home. Perhaps we need to start rounding those people up.

We begin to see suspicion of such people as common sense.

We begin to see the existence of such people as a grave danger.

We begin to think that something should be done about those people.

We begin to think that we should be the person to take those actions.

We begin to carry knives on trains.

You see?

We are no longer addressing a specific and immediate problem. We are no longer engaged in something of temporary duration with a clear goal and a clear end. We are no longer engaged on behalf of others. We are no longer checking to see if some other, stronger, braver, better power might be available to us. And we are instigating, using our fear of potential violence we imagine might come tomorrow as the only justification we need to deliver actual violence today. We are oriented toward violence. It is not a fix; it is a solution. Moreover, it is the solution—the only one. We think it will redeem the evil we see. And when the violence grows, we conclude violence has not yet redeemed the conflict only because there has not yet been violence enough.

The suggestion that we do something other than violence begins to seem dangerously weak. In fact, it seems like a moral failing, even a betrayal of the memory of physical bravery enacted on our behalf. It seems like siding with the enemy. I suppose you want to invite the terrorists over for tea, do you? Have you forgotten those who sacrificed for your freedom?

Rules preventing us from enacting any sort of “good” violence begin to seem ridiculously naïve. Suppose there’s a bomb set to go off in one hour and you have in your custody the only man who knows its location. . . .

If you found a society that had been captured by the idea that violence redeems, you would likely find a society that advocates torture. You’d probably find a society that spends an inordinate amount on weapons and armies—as much, perhaps, as the rest of the world combined. You’d probably discover a society that considers the unfettered ability to personally own weapons to be a more important human right than the right to health care or food or clean water or education. You’d probably find a society that believes strongly in the death penalty, and thinks brutality in prisons is a well-deserved and necessary part of any punishment, and thinks any victim of police brutality probably deserved it. You’d probably find a police force that looked more and more like a military, and you might discover that this force is oriented toward violence as a first response, particularly toward those people that this society has already decided represents presumed moral deficiency and theft and failure to earn life.

You might find that the concept of diplomacy is scoffed at in such a country. You might find a country that invades a country that has not attacked it, and frames this action as a defensive strategy. You might find presidential candidates in such a society suggesting that we murder the civilian populations of our enemies. You might find it’s an applause line. You might find presidents who boast, as evidence of their moral strength, that when they are hit, they hit back a hundred times as hard. You might find a country that believes any atrocity is allowable, provided only that some enemy might potentially do something that can be framed as similarly atrocious.

If you wanted to know which people such a society considered an enemy, you’d probably look for the people whose acts of aggression were never permitted, and for whom even the hint of potential aggression justified a hugely aggressive response—if response is the correct word to a hypothetical preemptive act. You might look for the people against whom acts of violence were rarely prosecuted. Or, to put it another way, you’d probably want to look for which people the police stood in front of to protect, and which people the police faced to oppose.

If this were a deeply ironic universe, you might even find that the people most aligned with all these violent ideas worshipped a deity who admonished his disciples to put their swords away lest they die on them, who presented an example of a God who would sacrifice Themself even to death rather than utilizing any of their infinite power to harmful purpose.

This is the conclusion: Other people not only do not matter, but it is their fault they do not matter, and it is good if, as a consequence for their failing, they are harmed. But it is even better if they are killed.

And, of course, every lie will levy a penalty upon those who believe it even as it endangers those who believe it and those who do not alike—because a lie fails to recognize reality, and reality will not be denied forever.

Here is the penalty for believing this lie: cowardice.

If the only best solution is violence, then I will be ready to enact it with less and less qualm from an ever-increasingly comfortable position. If I live in a world where violence redeems, then I will become more and more ready to allow it to be delivered to more and more people, even while the threat I perceive grows nearly as quickly as my fear of the world around me, grows nearly as quickly as the every-increasing proliferation of violence that I insist be enacted on my behalf to redeem my fear of that threat. And I will increasingly feel safer the more this violence is done on my behalf, by power structures who will make the violence happen automatically, without my even having to think about it, while I cower with my personal arsenal, hiding from everything that makes me afraid, which increasingly will be a list of everything that exists.

And here is the danger of believing it: harm.

The threat that I fear will inevitably grow, because, oriented toward violence, I am creating a world of violence to live in. If I insist on a world where violence redeems, eventually those I threaten will agree to meet me on the deadly battlefield upon which I have insisted, will attack me not from their strength but from their weakness, will try to redeem the problem of me using the very sword I have drawn.

A world in which violence redeems is a world that will inevitably kill me, maybe once, but more probably a thousand times.

So those are three foundational lies that any genocidal spirit seeks to establish: First, that we are not related; second, that life must be earned; and third, that violence redeems.

Once these lies are established, genocide becomes inevitable.

The tracks are laid. Now we can focus on efficiency.

You just need a little push. A little blame. An undue focus on crimes committed by a specific group. Build the largest industrialized prison system and the largest military ever known. Take police forces already trained to view specific neighborhoods as war zones, their residents as foreign hostiles, and themselves as an occupying force, and empower them to greater boldness.

Start testing certain concepts, speaking aloud ideas that have hidden for generations behind cover of euphemism.

Start saying we need law and order, by which you mean stopping people randomly on the streets and frisking them.

Start suggesting that our problem is an unbecoming timidity when it comes to violence.

Start saying that we need to bomb them until the sand glows.

Start saying we need to go after the women and children.

Start suggesting that an entire desperate population is a poisoned handful of candy.

Return to a policy of enforcing draconian drug laws in minority populations. Start praising dictators who murder suspected drug users in their own countries.

Propose a travel ban. Fight to enact it in court.

Start rounding people up. Split up some families. Get people used to that idea.

Conflate a vulnerable group with rape. Call them animals. Then go after the most productive and openly integrated and cooperative members of that vulnerable group, to make sure the totality of the dehumanization across the entire group is made clear.

When we feel threatened, suggest the answer is to kill all the people in a country.

All of these things are things I’ve heard in recent months from the White Christian president, accompanied by the cheers of some very fine people.

The Reframe is supported financially by about 5% of readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the upcoming essay collection Very Fine People, which you can learn about how to support right here. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He can clearly not choose the cup in front of you.

Comments ()