Always Do The Right Thing

Art that critiques its critics, cowardly pacifisms, and the violence that makes so many of us feel safe.

Confession time: I like movies. As an art form, they are, in my opinion good.

One of my favorite subgenres are movies that are constructed in such a way as to get their audience to tell on themselves. Martin Scorsese is pretty good at this, to give a prominent example; he often presents selfish people doing vile things because doing vile things satisfies their selfishness, and satisfying your selfishness can bring a lot of easy rewards—albeit sometimes rewards that carry inevitable consequences. And Scorsese shows all this behavior and these rewards and these consequences without putting too heavy a hand on the scales as to how he personally feels about all of it, which allows a lot of people to show the ways they openly admire such behavior, and desire the rewards, and ignore the consequences, which is exactly what a lot of fans of Scorsese films do when they talk about those films. And a lot of people don't understand the difference between depiction and approval, which is another thing a lot of detractors of those same films reveal about themselves in their critiques.

People can comment on art; this is known. Less discussed are the ways that art can comment on people.

My favorite example of a movie that gets its audience to tell on itself is Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, which is in my opinion a masterpiece. If I were to craft a personal ranking of the best movies ever made (and maybe someday I will), it would very probably crack the top 10.

I’m going to spoil this 35-year-old movie now. Consider yourself duly warned.

Do the Right Thing takes place over a single extremely hot day in Brooklyn, in a predominately Black community. It follows various people who live and work and play within a few city blocks: There’s the local drunk, the local busybody, some nice young kids, some nice older kids, some parents, some raconteurs, some agitators, a radio DJ (Samuel L. Jackson) who narrates the happenings in the neighborhood as if it were a story outside his window, and a wandering DJ named Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) who carries a powerful boom box everywhere he goes. There are cops who drift in and out, present but separate, vaguely threatening but mostly dormant. There’s a pizza parlor called Sal’s Famous Pizzeria that’s owned by an Italian man named Sal (Danny Aiello), and run by Sal and his two sons and their one delivery man, who is named Mookie (Spike Lee). The people in the neighborhood love Sal’s pizzeria. Sal is very proud of this, and of feeding the community, but he’s troubled that his oldest son, Pino (John Turturro), hates the pizzeria because Pino hates the neighborhood it is in, because Pino despises the Black people who live there, because the people in Pino's mostly Italian neighborhood are mostly bigoted against Black people, as, to some degree (as we will learn) does Sal. There are pictures of Italian people on the wall at Sal’s Famous, because Sal is very proud of being Italian. These pictures become a source of attempted controversy when a local hothead named Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), agitates for Black faces on the wall of fame in a pizzeria in his predominately Black neighborhood, though for most of the day nobody else in the neighborhood seems to take his efforts or his complaints very seriously.

It’s a gorgeous picture of a vibrant and boisterous community full of characters who all bounce off each other, a portrait of a community of often very messy and complicated people who despite their flaws and rough edges and bigotries, the film seems to very much enjoy being around—and because of this, we very much enjoy being around them too. You like these people, and even though there’s a fair amount of strife that bubbles up in the heat, you don’t want this day to end.

But it ends.

In the movie's devastating finale there is an ugly and entirely avoidable confrontation that begins with Buggin’ Out’s continued advocation (which has until now largely been played for comic effect) yet again for "brothers on the wall," a confrontation which is escalated by Sal, and re-escalated by Radio Raheem, and which from there keeps escalating, and escalating, and escalating, until the police arrive and murder Radio Raheem. They choke him to death, then pile him into their cruiser and drive away.

Mookie, a part of the horrified and traumatized crowd, takes all this in, then walks to a nearby trash can, picks it up, and hurls it through the window of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria. That act begins a riot, and in the riot, Sal’s Famous Pizzeria is burned to the ground.

When the movie came out, this ending was controversial—very controversial.

Mostly white pundits and mostly white audiences started having conversations about it, and the conversations were mostly centered around this question: did Mookie “do the right thing?” Why did he throw the trash can? Was he wrong to throw it? People really wanted Spike Lee to say Mookie was wrong. Spike Lee wouldn’t say that. Instead he pointed to the Malcolm X quote that made up the film's coda, which was about how self-defense in the face of violence was not violence but intelligence.

The potential celebration or at least condoning of violence became a major issue that audiences had with the movie—and by violence, I mean the riot, and the destruction of Sal’s Pizzeria, and to a lesser extent the fight that preceded it.

The mostly white pundits and audiences decided that this was a movie about whether the destruction of property is justified by an act of police brutality. The burning of Sal’s Pizzeria was a tragedy, worth discussing at length.

The tragic destruction of Radio Raheem’s body didn’t come up quite so much.

And I'd ask: Was this a movie about the riots and the destruction of property, and whether or not it is justified? Mostly white pundits and audiences seemed to think so, and started to express concerns that Do the Right Thing might incite Black people to riot.

Few seemed to also worry that police brutality might cause Black people to riot.

Yet the movie rather pointedly ends with listing of many names of Black people who had been murdered by the police in recent years—a reminder that police brutality was very much a thing even back in 1989, just like it is now, when cell phone video makes it much harder to ignore. So I'd argue this isn’t a movie about the moral ramifications of the destruction of Sal’s Pizzeria, but rather a movie concerned with the horrific effects of policing on Black neighborhoods; about the ways that policing in America represent the ongoing persistent historical violence that was already and overwhelmingly and almost unthinkingly being condoned by the very audiences that were most concerned about how a film about that violence might be condoning a violent response.

I think the reaction to Do the Right Thing revealed that the burning of a white-owned pizzeria and a fight over inclusion¹ represented violence that scared white audiences, while a persistent police presence in a Black neighborhood that might at any moment turn into the murder of a resident of that neighborhood did not represent violence that made white people feel scared. It might have even been the sort of violence that made many white people feel safe. In fact, most of the talk by mostly white pundits and audiences didn’t even seem to acknowledge the act of policing on Black neighborhoods to be violence at all.

Like I said, sometimes when people talk about art, the art starts talking about them.

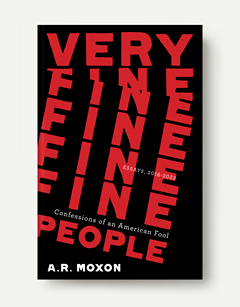

I’m publishing a book of essays called Very Fine People: Confessions of an American Fool, and my readership is helping me do that. If you want the details on how you can get in on that and get a signed copy and my thanks in the acknowledgements section of the book, click this link.

In 1989, everyone wanted Spike Lee to answer the question: Do you think Mookie did the right thing? What people missed was, Spike Lee had already answered the question, in the movie, for anyone who wanted to pay attention. He did this in such a way that people who weren’t going to listen wouldn’t hear it—which would allow his art to critique the people critiquing it.

Let’s watch the scene in which the doomed Radio Raheem gets his spotlight and tells the story of Right Hand Left Hand:

OK. Got that? It’s a metaphor.² It’s an important one.

The Love hand is the right hand.

And the Hate hand is the left hand.

The movie is called Do the RIGHT Thing.

Do you know what Mookie says before he throws the trash can? You can watch the scene and turn on the subtitles to catch it, but I’ll save time and just tell you.

Mookie shouts “hate!”

I hesitate to be the one who says This is what Spike Lee was really saying but ... damn, that seems intentional. Whatever the authorial intent, it's my reading of the movie.

In that movie, does Mookie do the right thing? The movie tells us. No wonder Spike Lee mostly declined to answer the question directly. He's answered it already.

Mookie chooses the left hand because in that moment hate is what is in his heart. And hate is what is in his heart because his friend has just been murdered by armed civic brutality squads that work in his neighborhood to enforce control of the predominantly Black residents with a persistent, ever-present violence; a threat that usually exists within that neighborhood as an unspoken threat but which occasionally and inevitably explodes into murder. It’s a violence that exists because the people in Mookie’s predominately Black neighborhood are not the class of people preferred by power, and daily ceaseless violence against the people in Mookie’s neighborhood is a violence that makes the preferred class of people—that is, white people—feel safe.

The question isn’t “did Mookie do the right thing?” The movie tells us what thing he did. We can all watch and listen. He chose the left hand, and he deliberately referenced his murdered friend while doing it. No wonder Spike Lee declined to judge Mookie. What choice was left to Mookie in that moment but hate?

The real question posed by Do the Right Thing is, why do the power structures of our society choose the left hand, at scale, to this neighborhood, and to thousands of other neighborhoods like it? Why does our society enact such daily ceaseless violence on these funny, flawed, strange, occasionally abrasive and frequently delightful people that we get to know over the course of a day? And why does that daily ceaseless ongoing violence, which makes the destruction of human life inevitable, seem to make so many people feel safe, while the destruction of property that arises when some of the people who live under that daily persistent violence finally do the left thing in return seems fill them with such fear?

It’s not the question that got asked about Do the Right Thing, though.

White pundits and audiences wanted to know if Mookie had done the right thing, and they wanted to know it so much, they never stopped and asked themselves, wait, are we doing the right thing?

I doubt Spike Lee was surprised about that.

I think that’s the point the movie was making: the police are an ongoing violence against Black people because ongoing violence against Black people makes a lot of people feel safe.

I’ve been talking about the bully tactics of narcissistic abusers, and the way that rising fascism can be seen as the application of narcissistic abuse at a societal scale. I’ve talked about how bullies seek to expand the margins of permission regarding the violence they intend to do to the people they target, and how they do it by framing their victims as violent threats, in order to frame their violence not as violence but as safety.

It’s the standard fascist playbook: to gain the support of a population by offering up themselves as providers of a violence that will create a great and overriding safety, in order to justify all the violence they intend to enact.

So the question I’d like to ask, while I ponder Do the Right Thing, is this: what violence is it that makes you feel safe?

You? Me. What violence is it that make me feel safe?

It's a hard thing to be honest about, I think. It's not a pleasant thing to realize about oneself. Once you realize it, though, it's hard to miss. I can’t count how many people have told me in recent years that the reason that police need more funding despite constant escalating brutality and impunity is because “defund the police” is a terrible slogan, and that it is a terrible slogan because the police make people feel safe despite their brutality (or, if we are honest, because of it), and that perceived safety of those who feel violence makes them safe is more important than the actual safety of those targeted by the violence.

We can’t defund the police, even though giving the police the majority of our civic budget makes us unsafe from so many things, not least of all the daily ongoing persistent violence that the police represent. We can’t defund the violence that police represent? Hell, we can even say it, or we’ll be blamed for causing it, even by people who claim to want to end it.

Many of us don’t even perceive of it as violence—that’s how safe the violence makes us feel. Even the slogan suggesting we diminish that security blanket rather than continue to grow it terrifies us, causes us to run away from even the attempt at creating a society that is actually safer, causes us to exonerate those who run away by finding their motives not only understandable but reasonable.

We’re abusing and murdering people at our border, by the way. We’re doing it because our national fascist party—that is, the Republican Party—wants to abuse and murder people at our borders, and they claim that’s because the migrants and refugees and asylum seekers at our borders represent an invasion that intends to murder us and replace us, even though they do not intend to murder us, and we do intend to murder them. And the party that would position itself in opposition to Republicans—that is, the Democratic Party—have been more than willing to accommodate them on this, because it seems that either they genuinely agree with the Republican premise, or else (I confess I think it’s more this one) they fear that for the majority of white U.S. voters, brutalizing brown people at our border is the sort of violence that makes us feel safe, and removing that violence makes us feel scared and threatened and endangered.

We could talk about many examples, but let’s talk about that one.

Here’s the thing about the narrative that people entering our country at the southern border represents “an invasion”: It’s a Nazi conspiracy theory. It’s a popular one. I get into all that in recent essays. Check the recent archives if you want more.

Republicans want to close the borders, and they want to abuse and murder people at the border, and they want concentration camps, and they want to send armies around the United States rounding up undesirables—a program which actually would be an invasion—and they say they want to do all of this to make themselves (the people who intend the most violence) feel safe from violence and economic disaster, and they insist to everyone else that it is necessary in order to be safe, and many of us believe them, and far too many are willing to accommodate them.

And in Texas (among other places) they say they’re willing to secede to be allowed to do it. By they I mean elected Republican officials. They’re also increasingly interested in a civil war, which they frame not as the insanely suicidal and murderous violence that it would be, but as safety and self-defense. People scoff at these threats, which is understandable, since they are ludicrous threats based on a ludicrous worldview founded on ludicrous lies. However, the fascist supremacist American spirit has tried to commit murder/suicide on the national level before in our recent past—a mere 160 years ago. So who knows but they might go ahead and try it again, because for our American fascist party, all violence is the sort of violence that makes one feel safe, and war is not an exception.

But here’s the thing about open borders: they are safer than closed ones, and they’re more economically generative, and they are exactly the sort of thing we ought to seek if we truly want to achieve safety from violence and foster economic opportunity. And I know that my saying this will make a lot of people think I’m being hopelessly naive and that what I’m proposing is not only foolish but dangerous, but this do me is indication of just how instinctive it has become, to feel safety at the thought of a border controlled through brutality and threats and murderous violence.

But it’s true, you know. Open borders are safer and more generative. This is why it would be absolutely suicidal for Texas (or any other state) to secede. Texas’ economy is going great guns right now, but it’s going great guns specifically because it enjoys open borders between itself and every other U.S. state, not despite this. If those were suddenly closed off, and if Texas were not able to enjoy the exponential generative effects of sharing expenses and profits at the national level, it would soon crater its economy and face a multitude of dangers that they could have avoided by simply keeping their borders open, even if it were able to avoid the total economic and physical devastation that would attend a war.

Go ask a country in the EU if being a part of a system of open borders generates more opportunity and safety than did the system of closed borders that marked the geopolitical reality of the 20th century. Or better yet, ask the UK, who opted out of the EU, whether doing so was a real shot in the arm for their economy or not, or if they feel more prosperous and safer after Brexit than before.

Or think about the Berlin Wall, to name another border secured by violence and brutality that Republicans have recently taken to praising. Did it create peace and economic opportunity, or was it a reflection of a political engine that generated the opposite?

Or think of the United States, which as a matter of historical face grew and thrived because of its open borders.

Open borders are safer than closed borders. Open borders create more opportunity and thriving than closed ones. Naive? I’d say observably true. Foolish? I’d say the real foolishness is believing that there is a violence against our fellow human beings that makes us more safe rather than less safe, especially when this sense of safety is being utilized by Nazis (or just people using Nazi conspiracy theories, if you like) as a pretext to start sending troops around the country to round people up, and to end democracy, and to increase the police state, which are violence that endangers us all.

How do we secure the border? Wrong question, I’d say. The right question is how do we engage in a new politics that will allow us to open our borders? The clear danger to human life at the border is the danger posed by us to those trying to cross it, not a danger posed to us by them. If there actually is a danger at the border, is it caused by the border being open? Or is it caused by something else? And if its cause by something else, how do we change that "something else" so we can enjoy the greater safety of open borders?

How do we expect others to do the right thing when we think doing the right thing is dangerous?

It’s a question that people won’t ask, if they’ve found a violence that makes them feel safe. The questions that people ask when they’ve found a violence that makes them feel safe ask usually focuses exclusively on the behavior of the people who suffer under that violence. We say that we’ll only support their right to exist if they always do the right thing, which we refuse to do ourselves. We choose a false and cowardly pacifism that demands a nonviolence that does not threaten us, while embracing a violence that makes us feel safe. We’re not brave enough for a true pacifism that might ask something of us, yet we demand it of others before we’ll consider helping them escape the ongoing persistent violence enacted against them on our behalf, all because it makes us feel so safe.

So we beat on, boats aligned with the current, pointing out every time those we harm don't do the right thing in response, never asking ourselves when we’ll start doing the right thing, which is what will finally be required of us if we ever want to actually live in a safer world.

The Reframe is supported financially by about 5% of readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the upcoming essay collection Very Fine People, which you can learn about how to support right here. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. When he’s following an angel doesn’t mean he has to throw his body off the building; somewhere they’re meeting on a pin-head calling him an angel, calling him the nicest things.

¹ Slyly (at least slyly if he was hoping to receive the sort of reaction that made his point), Lee made sure this was a rather pyrrhic and meaningly symbolic fight for inclusion, drummed up by one the movie’s more unreasonably obstreperous characters.

² And a nice nod to Night of the Hunter, another masterpiece.

Comments ()