America Returns To Brunch

Brunch? Brunch is awesome. But know what your levers are, and know who is pulling them.

Note: this essay was originally published on Revue on January 17, 2022.

I’m writing this two days ago, which is on Saturday, January 15, 2022.

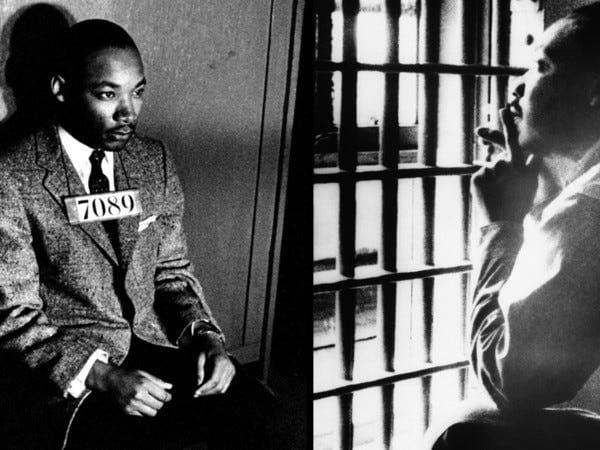

Ninety-three years ago today, Martin Luther King Jr. was born.

You’re getting it on January 17, 2022, when we observe that birthday—many in recognition that a moral giant walked the earth among us, many because we simply enjoy a day off from work.

“Walked the earth among us” includes me figuratively, but not in actuality. Martin Luther King Jr. and I didn’t cohabit on this earth. Fifty-four years ago this April, while in Memphis in solidarity with striking workers, he was murdered, as our FBI for example dearly hoped he would be (though they have washed their hands of any culpability, finding a man who was convicted for the murder) and many of his fellow Americans mourned.

Also, many of his fellow Americans celebrated.

If one is interested enough to check the historical record, you’ll discover that at the time of his murder, Martin Luther King was one of the most hated men in America. He was cast by his critics as divisive, radical, controversial, a rabble-rouser stirring people to anger and hatred and violence, by calling relentless attention to our structural injustices. His murder was a joyous event for many—a celebration.

The celebrants were heard cheering, laughing, joking, by those who mourned. No census was taken of them, but they would have been mostly white, and also mostly Christian, which means people who claim to worship Jesus Christ and revere his life, and follow his example and his teachings. Jesus was another moral giant of his day, one who King himself believed in and followed and served as a minster.

Jesus was a guy who said that you’d find God by aligning with those who are already at risk. Perhaps that’s why King found him compelling. The empire of Jesus’ day also dearly hoped he would be murdered, and then he was indeed murdered, and the empire of the day washed their hands of it, if the book is to be believed.

We might conclude that moral giants aren’t often popular within the empires of their days, if we have the knack for pattern recognition.

Because we are observing his birthday today, and because his position as a moral giant has been firmly established, we will be subjected to a parade of politicians who claim to revere King’s life, and follow his example and teachings, and who also happen to be actively working to demolish everything King ever stood for: voting rights, social and economic justice, equality under the law. They’re mostly men, mostly white, mostly Christian¹—and they’ll be paying him their own form of tribute.

I’ll paraphrase this tribute.

The tribute involves a solemn reminder that between the dates of his life and his death, Martin Luther King said exactly one thing, which is that we should not judge people by the color of their skin but the content of their character. They will then (if pressed) explain that this means that there is no such thing as racism anymore, and any discussion of how racial attitudes inform our past formation or present trajectory is itself racism, because during Martin Luther King’s lone speech, he took America’s sin of racism into his body, and then he took it with him when he died, and racism was expunged from this country forevermore, and therefore anyone who suffers in our perfect and absolved land suffers because of a defect of character, not because of our national sins, which have been forgiven, even if they still seem extremely present.

This politician’s tribute isn’t very sharp on what the man actually said or meant, but then they’re not very sharp on what Jesus actually said, either, and by their lives they pay Jesus a similar tribute, similarly working against what he claimed to be about, while very much appreciating him for using the occasion of his death to take every one of their sins away, even though their sins still seem extremely present.

I guess if you had the knack for pattern recognition, you could conclude that once moral giants are dead, people who would have hated them begin to use them, to make them say whatever is convenient to them. If you read the Christian Bible, you might even find something somebody said about the people who build tombs for the prophets.

Also: there’s a deadly pandemic going on today, and these same politicians who offer tributes to King are working very hard to make sure it keeps going on, and while I wouldn’t dare presume to assign motives to people when I don’t know their most inner souls, they’re doing it because it benefits them politically, and we all know it.

Oh and they’ve broken the post office, because it benefits them politically, and apparently that’s not something that can be fixed, and if you suggest that it actually seems simple enough if we try, so maybe it can be, you’ll be scolded that our new president is not a god.

And the hospitals and school are near the breaking point, which you know if you are close to anybody who works in health care or public education, or as long as you’re not trying very hard not to know. And so on, and so on.

So that’s where we are in the United States of America in the year of our lord Jesus Christ 2022.

Anyway, let me change the subject. Here’s what I’m thinking about today: brunch.

Who doesn’t love brunch?

It’s the best. It’s not quite breakfast, it’s not quite lunch, but it comes with a slice of cantaloupe at the end. You don’t get completely what you would at breakfast, Marge, but you get a good meal.

Brunch. Man. I want to go get some right now.

We all would like brunch, I think. The problem is, pandemic. It’s out there. But maybe we’re vaccinated. A miracle, the vaccine—truly. It freed a lot of us from potentially deadly or debilitating risk in 2021. We had a summer. We had an autumn. We went places.

We went to brunch.

But maybe we’re aware that a lot of people refused the vaccine, largely for political reasons, and also our political systems failed to engage in the sort of massive coordinated global and national effort that would have been required to deploy the vaccine and testing globally, failed to circumvent the obstacles of intellectual property and logistics and politics that needed to be overcome in order to vaccinate our interconnected world, failed to impose any of the politically challenging inconveniences proven to prevent the spread, and so now we have a variant that’s more successful at circumventing the vaccine.

If we’re vaccinated we can expect to avoid all the worst results. So maybe we’ll go get that brunch anyway.

But we might also be aware that there are others who medically can’t get the vaccine, or that there are some who can safely get it but can’t expect the same degree of protections, or to be confident in their bodies’ ability to fight off even a mild case.

These people are at risk.

Some are immunosuppressed. Some are older. They’re in bodies that are failing but not failed, or not failing at all but not as fully functional in certain ways as others. And they also want to live. And, if we get infected, we might not suffer, but we might infect them, might make living harder for them. And if everyone acts as if infection is no big deal, then maybe the dread of pandemic never ends for them—ever.

And then there are those who cultivated a practiced ignorance, refused vaccination for political purposes. Perhaps our sympathy is diminished for them—maybe we’re even furious at them for aligning with those who chose to bring us to this place. But maybe we still don’t want them to die for their ignorance. Or, even if we can’t find it in ourselves to extend that mercy, we don’t want them to infect others who are at-risk, nor do we want them to choke the hospitals, and strain the schools, and generally make life less safe for everybody—particularly those who are at risk.

So maybe we decide there’s no brunch for us for a while—until this wave has passed at least.

Maybe we order takeout instead, and maybe we cancel that one trip, and we watch the infection levels, and we factor more people than just ourselves as we make our risk assessments. Maybe we act as if we’re still in the pandemic that we’re still actually in, in recognition of the fact that we live in a society, and other people exist.

Maybe we learn to live with the awareness of this thing that exists, and recognize the ways our systems seem incapable of rising to meet the challenges of this moment, and start expecting better, and more.

Maybe we demand vaccine mandates, and courts that will uphold them.

Maybe we demand politicians who will enforce health guidelines, and do whatever it takes to make testing free and easily available.

Maybe we demand leaders with the will to lead, and to make necessary and difficult calls even if they’re unpopular.

Maybe we expect solidarity from our friends and neighbors.

Maybe we learn to expect a society that protects people who are at risk, rather than neglecting them for convenience.

Maybe we stop tolerating intolerable things.

Or maybe we don’t.

Maybe we decide to find a reason to not care, because we no longer feel personally at risk.

Maybe we decide to make certain compromises, in accommodation of those who don’t want to care, at the expense of those who don’t have the privilege of deciding whether or not to opt out.

That would be characteristic of us as a general group, if I’m being honest.

We’re a convenience society. We tend to take convenience, if we can afford it, or make somebody else pay for it.

Here’s what I’ve noticed lately: More and more people are saying “we need to learn to live with the virus” and what they actually mean is “we no longer intend to live as if the virus were a present reality, and we’re fine if somebody else needs to learn to live—or die—with that decision.”

They’re saying things like “I’m sick of this” and “enough is enough,” which is perfectly understandable, and the way literally everyone I know feels, but it carries the implication that by this they no longer mean the virus, but the need for solidarity the virus exposes.

A lot of people are saying “everyone is going to get it eventually” as a way of making themselves feel better about letting themselves off the hook for any responsibility, as a way of saying “so I no longer have to care about who gets it.”

I’ve noticed that a lot of people say “it’s endemic,” and what they mean is not “therefore we need to demand that our systems of power make a lot of changes to accommodate that new fact, in the interests of public safety” but rather “so now we need to stop trying, and whoever dies was just fated to die, but I’m pretty sure it won’t be me.”

It’s almost as if the reason that our systems of power failed to rise to meet the challenge of this moment is because they knew that once an outrageous neglect becomes systemic and mostly localized with a minority, then people accept the outrage for the sake of personal comfort rather than engage in sacrifice for the sake of civic solidarity … and they were counting on that.

Power and wealth knew the needed structural changes would carry a cost that power and wealth clearly do not want to pay. The money, yes—but also the reconfiguration about how we think about society, and what sorts of things are possible in order to accommodate human beings. That would be the true cost to them, I think.

But they know we want our brunch.

So what am I saying here?

Am I saying that brunch is bad? Hell no. I love brunch. We’re not attacking brunch.

Am I even saying wanting brunch is bad? No I am not. It is natural to desire good things, and brunch is a very good thing.

Am I saying going to brunch is bad? I’m actually not even saying that. There are situations even now when going out might be appropriate. We all measure our risks. It’s just that some of us measure risks only to ourselves.

What I’m saying is: get brunch, if you can—but be aware of circumstance, and make your precautions for more than just yourself. Consider who might be paying for your brunch, and what that price might be.

And, this: know what your levers are, and know who is pulling them.

It all makes me think of the signs—signs about brunch.

They popped up at protests right after the popular white supremacist and fascist Donald Trump was elected president. You’ll remember them when I show you.

Here’s one:

I know what’s meant here. The election of Donald Trump was a unique danger, in a way the election of Hillary Clinton would not be. Trump’s election was such as shock to the system that it forced protest from those who would otherwise be engaged in comfortable routine.

And I’m glad the people who protested protested. It’s good that they did. They weren’t wrong about Trump.

But, I also remember in those days listening to the reactions to those specific signs, from people who had been working hard at the struggle for equity and equality for a very long time. They were people who weren’t expecting much assistance in their struggle from Hillary Clinton, if you want to know the truth. Did they vote for her? Mostly, yes. In fact, they had a far more close and personal and immediate awareness of the dangers Donald Trump’s election and his movement posed, because they were, for one or more reasons, the targets of the viral hate he represents.

They were at-risk.

But also: they knew what they were getting.

Their struggle for equality had been going on for a very long time, and Hillary Clinton in most ways represented a status quo that demanded of them slow and incremental changes. She represented a status quo that undergirded the power structures blocking them, a status quo that was always willing to make pragmatic strategic concessions when it came to their struggle for equality and equity, that was always willing to make their struggle to survive the first concession.

And also: the stakes for them were not brunch.

It turns out those brunch signs (and others like them) were communicating much more than the holders knew.

They communicated the stakes of the struggle for the holder, and the likely limits of the extent of their support.

It communicated that the holders weren’t so much protesting the injustice that had been exposed, as they were protesting the fact that it had been exposed to such an uncomfortably unignorable degree.

They communicated the holders didn’t want the sort of sweeping changes to the national spirit that such an exposure demanded, the sort of structural modifications that would bring true equality. They wanted the sort of return to the familiar status quo with which they had already made themselves comfortable.

The signs stated what those for whom awareness and struggle knew quite well, because they’d seen it before: that the holders just wanted to go back to the previous comfortable unawareness, as soon as possible, please.

They didn’t want anything extreme. They wanted things to be the way they’d always been.

They wanted their brunch.

Again: I’m not attacking brunch here.

I’m not even attacking the desire for brunch.

I’m not even attacking.

Am I against comfort? I am not. Comfort is a common thing to want.

Am I against relief? I am not. We all should demand it.

I want my brunch, too. But I know what I know.

Don’t you?

My issue is unawareness, particularly when it is deliberate.

My issue is what the price for my comfort and relief is, and who will pay.

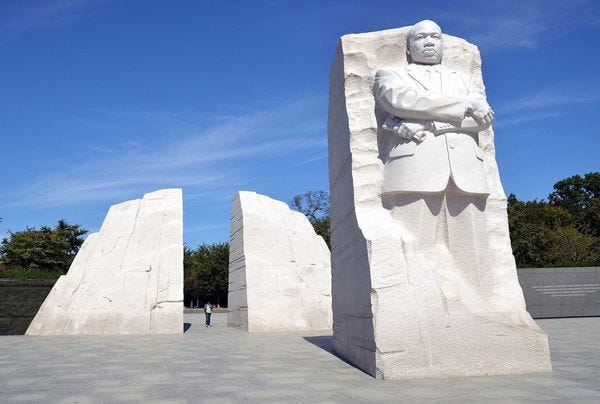

Which brings me back to the man whose birthday today is an occasion of national celebration.

It turns out that, despite what oh-for-example Mitch McConnell might suggest, the moral giant Martin Luther King Jr. said more than one thing between the dates of his life and his death. He said many, many, many things: about racial justice, economic justice, structural power, and the rest.

King realized “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” He knew that racial injustice didn’t just harm Black people, but all people, because racial injustice is built on lies, and any building with an infirm foundation must fall.

For example, a people who cultivate a culture of indifference to racial injustice or economic inequality might become the sorts of people to believe they can opt out of a viral pandemic, even as a million people die, even as hospitals and schools fail.

King realized that indifference to injustice was ultimately an existential threat.

And then he was murdered, and there was much mourning, but also much celebration.

He was a far better writer than me. Despite the fact that the contrast will not redound well to me, I’d like to finish with some words of his from a letter he wrote from a Birmingham jail.

A lot of the Christian bible is comprised of letter written from jails. I think Christians would be wise to add this one to their canon.

It’s the letter that has the rather famous line, revealing his “regrettable conclusion” that white moderates devoted to order rather than justice posed a greater and more painful block to civil rights than even overt racists.

You should read it all. It would be a good way to observe the day.

I’ll just quote a bit.

I had also hoped that the white moderate would reject the myth of time. I received a letter this morning from a white brother in Texas which said, “All Christians know that the colored people will receive equal rights eventually, but is it possible that you are in too great of a religious hurry? It has taken Christianity almost 2000 years to accomplish what it has. The teachings of Christ take time to come to earth.” All that is said here grows out of a tragic misconception of time. It is the strangely irrational notion that there is something in the very flow of time that will inevitably cure all ills. Actually, time is neutral. It can be used either destructively or constructively. I am coming to feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of men willing to be coworkers with God, and without this hard work time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation.

And then there’s this, from a bit later in the letter:

So the question is not whether we will be extremist, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate, or will we be extremists for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice, or will we be extremists for the cause of justice?

That’ll do.

Let’s all enjoy the day off.

_____

¹ They’re mostly Republican, too, in 2022. It’s a much more partisan thing than the celebration of Martin Luther King’s murder. We’re more politically polarized these days, compared to then. It’s our biggest problem, I’m told.

_____

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places. People often ask him if he has any words of advice for young people.

Comments ()