Profanity and Obscenity

The difference between profanity and obscenity, and why it matters.

Note: this essay was originally published on Revue on January 31, 2022.

And now ladies and gentlemen for your entertainment and delight, I will recap last week’s most important news story.

There’s this guy who … how to put it? He kind of sucks. His career is devoted to strategically deploying toxic ignorance and hack political trolling. His name is Peter. His dad has a similar sort of gig for the same network. Last week, Joe Biden, who is the president, called Peter a “stupid son of a bitch” and a hot mic caught it.

And that’s the story. I’m getting better at this brevity thing. Feels like it might be the soul of … I don’t know, something or other.

So! We have a profanity on the open field! Flag on the play!

Let’s discuss it.

Perhaps we’d do well to make a contrast between “profanity” and “obscenity,” to better focus on an important distinction that often otherwise becomes muddied.

Let me suggest “profanity” as language that breaks agreed social rules of propriety. Some people call them “curses.” It’s fractious language.

Meanwhile, let me suggest “obscenity” as something that violates fundamental standards of decent human behavior. Some people call this “abuse.” When made systemic, it’s injustice.

There’s enough adjacency to cause confusion, I know. In both cases some generally accepted rules have been violated. And curse words are also often called “obscenities,” so unless we’re thoughtful about it, we might understand the two terms to be completely fungible.

Some examples to make the distinction plain:

George Carlin’s “seven words you can’t say on television” is a hilarious and cathartic example of profanity.

Using the power of television to disseminate misinformation about vaccines, encourage selfish ease and complacency, and erode trust in public health officials and measures during a deadly global pandemic is an obscenity.

You see?

Maybe a little more unpacking is in order. Profanity can become obscene, and obscenity can involve cursing, after all. Don’t crack dirty jokes during grandma’s funeral. Don’t scream curse words at a 3-year old.

This might help: realize that in neither case is the actual curse word—the profanity—the actual obscenity. What’s obscene in the first case is violating the memory of a beloved elder, whose loss everyone has gathered to mourn, with grotesquerie, just as the wound of absence is sharpest. What’s obscene in the second is attacking a still-forming psyche with the violence of screams.

The profanity is present, but the profanity only serves to underscore the obscenity.

But then again … what if grandma was a bit of a scamp, and that dirty joke was her favorite, and everyone knows it, and deploying it actually helps the mourners remember her best? What if the 3-year old is wandering into the path of an oncoming farm combine, and what’s most needed is a warning, whose urgency might be enhanced by the presence of a profanity?

It’s never the words used. It’s what you use them for.

It’s the question of why you’re using them.

Should a president have called a journalist a “stupid son of a bitch?” I guess it would be preferable if he didn’t, even if his frustration is understandable. I think it would be even more preferable if we didn’t call somebody who does what Peter Doocy does (while working for who he works for) a “journalist.” But the whole question is a smokescreen.

Everyone expressing outrage over the incident is pretending, and we know it.

Years ago, when the Affordable Care Act passed, Joe Biden celebrated by saying that it was “a big fucking deal,” which was a profanity. To be fair, I don’t remember if all the people who had worked so hard to keep health care as unaffordable as possible for as many Americans as possible expressed shock and outrage at this profanity, nor do I care how they felt about it, or pretended to feel about it.

Years before that, Dick Cheney, on the floor of the U.S. Senate, told Patrick Leahy “fuck yourself,” which was a profanity, and I am and remain offended by the incident—but it’s not the profanity that earns my outrage.

Years later, Donald Trump bragged to Billy Bush that when it comes to women, his approach was to “grab them by the pussy.” It was a profanity, one of many from an endlessly profane man dedicated to every conceivable obscenity—but it was also a boast about his habit of using his fame and power to enable serialized sexual assault. And a bit after that, as president, Trump suggested NFL owners “get that son of a bitch off the field,” indicating players kneeling during the national anthem to protest our national pandemic of racialized police brutality. And then, a little later, he called journalists “the enemy of the people,” an utterance which did not contain a single swear word, and which his political supporters seemed to have very little problem with.

More recently of all, upon entering Congress in 2019, Rashida Tlaib said of Trump that she intended to “impeach the motherfucker,” which she later did do, twice, because (as was by then very clear to see) that motherfucker needed impeaching.

One might suggest that it’s hypocritical of me, to fail to find offense with Biden, while at the same time finding offense with Cheney and Trump; or to find offense with Trump but not with Tlaib.

In my opinion it’s not. It’s just noting the foundational difference between profanity and obscenity, and refusing to be confused by the cosmetic similarities.

In this culture we all understand this, I think. Most of us aren’t offended by curse words just as curse words. None of us are, regardless of political persuasion.

Some pretend otherwise, to gain their advantage.

We know by now they’re just pretending.

Jim Banks @RepJimBanks

Have we ever seen a President attack and malign the free press like Joe Biden has??

6:17 PM - 24 Jan 2022

When George W. Bush was caught on a hot mic calling a reporter “a major asshole,” he was rising on the broad support of certain groups of people who generally treated any use of any profanity as obscenity. We expected him to lose at least some support from them as a result of his contretemps.

He didn’t. He gained. When it came to profanity, they were pretending.

Later, when Dick Cheney told Leahy to go fuck himself, it was because Leahy was questioning the Bush Administration’s close ties and dealings with the company for whom Cheney had served as CEO, and Cheney knew full well he had impunity to do whatever he wanted. Cheney broke propriety to demonstrate his impunity to the Senate. Cheney’s company made billions off the Iraq War when Cheney orchestrated the lies that brought us to war in Iraq, which is an obscenity.

It’s the obscenity that ought to offend.

Later still, when Biden said “a big fucking deal,” he was celebrating a bill that would save thousands of lives. He accidently broke propriety to show his exuberance. I happen to think that, while Biden was characteristically maladroit, he was correct: it was a big fucking deal to a lot of people. I think most of us are fine with that, actually—and the people who were offended weren’t offended by the curse word; rather, they happen to believe that making health care affordable is an obscenity. In much the same way, it wasn’t the fact that Trump said “pussy,” it’s that he bragged about grabbing them. Cursing doesn’t offend us just for cursing’s sake.

So yes: Trump bragged to Billy Bush about being a sexual predator. Later he mocked his many many accusers—women with experience of what he bragged about—in front of a cheering crowd. Later he nominated a sexual predator to the Supreme Court, and mocked that man’s accusers in front of a cheering crowd.

It’s the obscenity, see.

Trump has spent his entire political life attacking journalists, our democracy, and the very notion of truth, and the rule of law, and all our finest principals, while promoting every kind of bigotry. He called African countries shitholes. He treated Puerto Rico as if the people there were no part of us and left them to drown. He defended the Nazis who occupied Charlottesville. He pushed a travel ban based on religion. He refused to fight a pandemic for political gain. The list could literally continue for a hundred more pages: obscenity, obscenity, obscenity, obscenity.

He’s done so to cheering throngs who all think this makes us great again, or are willing to look the other way to secure some perceived advantage. They’re ready to vote for him again, or whoever else might best capture the spirit in which he moves. Their support never wavered.

Trump’s supporters can pretend it offends them to hear that word, but we’ve seen them cheering in his crowds and we’ve heard what they cheer for.

We know they’re pretending their outrage.

We knew they can tolerate cursing.

We know they aren’t concerned about attacks on journalism, or of journalists.

And we’ve seen how comfortable they can make themselves with obscenity.

Which brings me to the real reason I’m thinking about this: right now Republican legislatures and school boards are banning books that they think will make their children uncomfortable, by which they inevitably mean that it might make their children aware of the historical or current existence of some form of systemic bigotry. Banning books to obscure marginalized voices—a classic obscenity, one that usually prefigures greater obscenities. And one of the most common objections of these modern banners is a predictable one, and a traditional one—the existence within the text of profanity.

We’re meant to still believe that an ideology that reveres Donald Trump still cares about protecting their children from profanity.

And we’re meant to believe it’s a coincidence that the fact that the works being pulled from school library all come from marginalized voices.

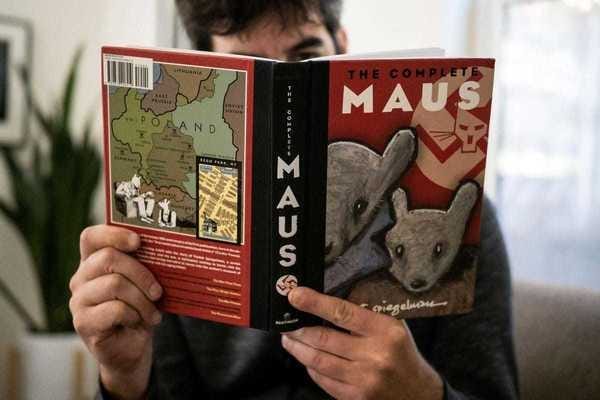

A few months ago, a Texas school administrator suggested that the new state laws against Critical Race Theory would also mean that any teaching of the Holocaust would have to present both sides of the matter. Yes, and in what I imagine we’re supposed to take as a total coincidence, this week a school board in Tennessee banned Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize winning story of Auschwitz and the Holocaust, Maus.

The rationale given by the county school board for singling out this story for removal—a powerful story that gives a specific and Jewish perspective on this obscenity enacted against Jewish people—is a predictable one: it’s nothing to do with silencing voices or sanitizing history, no: it’s just there’s profanity in it.

Don Moynihan @donmoyn

TN county school board votes to remove use of graphic novel about the Holocaust, Maus from school curriculum. Complains about vulgarity and naked pictures. https://t.co/fUynX6Mu7g https://t.co/v1fkaCMt2N

6:00 PM - 26 Jan 2022

This illustrates the reason it’s so important to distinguish between profanity and obscenity: our culture has been historically defined by abuse by the powerful against those without power, and by a systemic enablement of that abuse.

There are abusive families out there. Abusive families all have their differences, but I think one key similarity is this: if you want to understand the nature of the abuse, you discover which topics can’t be spoken. We don’t talk about Bruno, as they say.

As with families, so with countries.

Abuse relies on enablement. Enablement relies on silence—and powerful abusers know this.

(A word on the concept of “can’t be spoken.” We often see that an abusive person strategically accuses others of their own intended abusive behavior, to insulate themselves from the report of their abuse. And it’s true that people within the regressive political ideology to which these book banners belong have spent the past years complaining about the fact that there are things that “can’t be spoken” anymore. And then they say them. And maybe they get criticized for it, or maybe there’s some social consequence—which is what they always meant by “can’t say"—but there has never been any sort of law constraining them from their as-always protected language. No, instead, as we can clearly see, it is they who are engaging in the systemic, organized, strategic legal codification of silencing voices they find offensive, with the presence of profanity one of their favorite pretexts.)

Those who desire obscenity also engage in profanity, of course. They do so for many reasons, but one of the strategic ones is to muddy the difference between fractious language and deliberate harm and abuse. They’d like you to confuse the one for the other—because their victims engage in fractious language, too, and powerful abusers know this.

If your response to profanity from somebody engaged in exposing the reality of a present obscenity (or especially profanity from somebody presently living under the menace of empowered harm and abuse) is to castigate that person as just as bad as the abuser, you take up for the abuser and the abuse.

"If we talk like they do, we’re just as bad as them.”

No. Nope. Not even if it’s an f-bomb every single other word. The curse is not the obscenity. The abuse is the obscenity. Don’t take up for powerful abuser by agreeing to their false terms.

Is discreet language bad? No.

If discreet language is important to you, my recommendation is this: engage in discreet language yourself—yourself.

Scolding or distancing yourself from those who don’t use discreet language is just your way of laundering your own reputation, which creates distance between yourself and those fighting abuse.

Getting that distance is what powerful abusers, who could care less about discreet language, are counting on when they pretend their outrage about profanity.

They usually get it.

If you’re confused about who is being abusive here, just ask yourself: who is trying to present a larger and growing number of different traditionally and historically marginalized voices, and who is, right now systematically, strategically, for the accommodation of their own psychological and political comfort, banning books that expose real obscenities?

Maybe just asking yourself that last part should be enough.

Don’t get confused. Don’t agree to false framing presented in bad faith.

Always fight the obscenity; fight the abuse.

(And Peter Doocy can go fuck himself.)

_______

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places. In his younger and more vulnerable years, his father gave him some advice that he’s been turning over in his mind ever since.

Comments ()