Sabotage: Part 14 - The Vineyard And The Mountain

Wrapping up a series on repair and sabotage of repair. We frequently talk about redemption. We rarely talk about reparation. As we finish, it’s worth pondering why.

Note: this essay was originally published on Revue on November 27, 2022.

Intro | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 |

Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 |

Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 |

Good morning. The leader of the Republican Party and presumptive 2024 nominee is Donald Trump, believe it or not. This week he met with Nick Fuentes, who is a literal proud and open Nazi, for a strategy session.

It was an accident, we’re told. Trump didn’t know who Fuentes was, which is odd since Fuentes was one of the Nazis who marched in the murderous “Unite the Right” Charlottesville demonstration five years ago—Nazis who Trump incidentally later defended as Very Fine People, though there are many who insist that Trump wasn’t defending the Nazis, but rather the non-Nazis who marched with the Nazis for apparently non-Nazis reasons. Anyway, Republicans have had many of these accidents in recent years, so many that an attempt to catalogue them would probably double the length of what is likely to already be a very long essay.

So many Nazi accidents. Man. Republicans are so accident prone. Unlucky.

In a completely unrelated story, last week a man already known by local authorities to be a danger to others entered a Colorado Springs LGBTQ club and shot until the patrons subdued him and he could shoot no more.

And all the usual people—such as Lauren Boebert, the white supremacist and insurrectionist Republican representative of nearby Colorado district 3, such as Tucker Carlson and Matt Walsh, and an endless parade of other power brokers and propagandists who had spent the preceding years vilifying and demonizing queer people and inciting violence against them—all acted temporarily shocked! shocked! that somebody had gotten some of the guns they made sure were easy to get and killed some of the people they had said didn’t deserve to live. It was the whole usual thoughts and prayers thing.

And then they did an interesting thing, by which I mean a horrifying thing. Within less than 24 hours, they pivoted; started saying that the reason this man murdered queer people is that queer people insist on existing in our society, and unless queer people disappear themselves, then the natural and expected and appropriate response will be more gun massacres in more gay clubs, until queer people are gone, one way or another. These conservative fascists finally succumbed to the inevitable, and vocally took the side of the shooter in the matter of a hate crime massacre—which they have always done in all but word: by creating a world where anyone who wants to kill a lot of people is easily able to do so; by creating a political-media atmosphere designed to radicalize people and give them an inexhaustible supply of ready targets; and by creating a world where massacres are not only likely but inevitable and plentiful and targeted.

It is genocidal talk—quite literally. An intent to make millions of people not be. There are many, many, many, many, many, many other stories like this as well. Many other deaths. Many other thefts. Endless suffering, as people who have been deemed to not matter are forced to pay the high cost of brokenness.

OK, but you all know this. So what’s my point?

I guess it’s this:

There comes a point when an accident isn’t an accident anymore.

There comes a point when deniability isn’t deniable.

There comes a point, I think, when people who have good qualities stop being “good people” and start being people who are lending their good qualities to monsters who have promised to use those good qualities to facilitate atrocities, who have promised to get their own monstrous hands bloody on behalf of the Very Fine People; people who lend their many good qualities and their quiet support, retaining reputational goodness while facilitating atrocity—a state which I have been calling “blameless supremacy.”

There comes a point when we have to recognize the atrocity is already happening and has been for a long time, and those good qualities have been squandered.

There comes a point when everybody has had a chance to know better, and if they still don’t know better, we have to assume they don’t want better.

There comes a point when you’ve joined what you’ve joined.

There comes a point when fascism and supremacy is on the rise, when we have to choose sides.

I think we reached that point a very long time ago.

I wonder if we ever left that point, to be honest.

And there are a lot of people who will look at all these events, and their first question isn’t “Oh my God, there is significant danger here to marginalized people! How do we stand with the people who are threatened by this rising tide of fascist hate and violence, to surround and protect our friends and neighbors, our siblings and parents?”

The first question asked—really the only question asked, usually—is “Oh my God, there is significant danger here that we would paint these aggressors with too broad a brush, and cast them as irredeemably bad by exposing the things they support! How do we appeal to their better angels, and establish a path for redemption?”

How, indeed?

I wonder how many people who ask for redemption actually want it.

Here in my country, which is the United States, we greatly value redemption.

We don’t talk as much about reparation, unless it’s to talk about why it’s impractical or dangerous or impossible. But we love to talk about redemption.

But OK. I’m game.

Let’s talk about redemption.

Maybe you've noticed that it's getting harder to truly know what's going on these days. Legacy media—controlled by corrupt billionaires and addicted to the false equivalency of balance rather than dedicated to the principle of truth—has failed us. I am recommending that if you have money to do so, you subscribe to independent sources of information instead. This week I'm suggesting you support Wikipedia, which is an open source of information—one that has been targeted by sad boy and famous rubbery megalomaniac Elon Musk specifically because it provides information without being owned.

(If you also want to support The Reframe, there are buttons to do so all over the place and whatnot.)

If you’re still reading, I consider you a friend.

We’ve been damn near half the year on this subject. Thanks for your patience. Let’s take one last look back at where we’ve been.

We’ve been looking at brokenness caused by natural degradation, but also caused by injustice, abuse, and corruption. We’ve looked at the ways we yearn for repair, and yet repair never comes.

We’ve been talking about reparation—literally, the progressive process of repair—which begins with an awakening to awareness of what is broken, and moves to conviction that what is broken can and should be fixed, and that we share a responsibility to fix it. And conviction moves to confession of new awareness and conviction, to bring that awareness and conviction into the atmosphere of public consciousness and collective action. And confession leads to repentance—that is, realignments of our resources and intentions and systems and goals, away from managing unsustainable brokenness and toward repair, maintenance, improvement, and payment of the attendant natural costs of disruptions, money, time, and even the benefit and privilege many of us reap from brokenness.

We’ve also been talking about a supremacist spirit, which is committed to the foundational lie that some people do not matter, which is opposed to any payment of cost, and which sabotages the process of repair by deliberately making repair more costly: with suppression—ignorance that swallows our awareness, complacency that smothers our conviction, denial that refuses our confession—with oppression that makes re-aligning repentance a punishable crime, and with war that elevates opposition to repair to the level of physical destruction.

And we’ve been talking about enablements of each step of supremacist sabotage, each of which validates sabotage, creates a nurturing cradle for abuse and corruption and injustice, and allows supremacist intention to become entrenched and empowered supremacy. We’ve contemplated an unprincipled neutrality that enables ignorance, an unstrategic compromise that enables complacency, an undeliberative exoneration that enables denial, a lazy reconciliation designed to maximize comfort by accommodating oppression, and finally a pre-defeated surrender offered to avoid the cost of every necessary fight—a surrender which incentivizes and encourages aggressors to threaten endless war, and enables the inevitable violence of supremacist aggression and domination.

Last of all, we’ve been talking about the tools of reparation available to each of us to combat supremacist aggression and supremacy’s enablers: of a simple witness to truth that simply observes what is without seeking permission of any authority to do so, of a rugged hope that rejects easy cynicism and cheap optimism to insist that unlikely but necessary change is not only possible but imperative, of a moral clarity that locates brokenness within itself first so that it can impeach all brokenness it sees with undeniable authority, of a solidarity that refuses to abandon to oppression any member of its human family and willingly meets the resultant strife, and of a defiance that seeks no fight but remains determined to fight any necessary fight that arises in order to hold to its commitment to repair broken things.

I think every act of repair—every step of repair, every use of every tool of reparation—is an act of defiance against supremacy and sabotage.

And I think the work of reparation—including paying the costs of repair—is redeeming work. It’s the only path to redemption I know.

So that’s my answer to those whose first priority, in a time of rising atrocity, is establishing a path for redemption.

You want redemption? You truly want to redeem?

Then repair what is broken. Fix abuse, corruption, and injustice, so we can address natural repair and maintenance.

Pay the cost of reparation: disruption, wealth, comfort, and privilege.

You’ll make the path to redemption you claim to want by walking it. I fear it’ll be a rather fresh trail you’re making, but you’ll make a trail for others to follow. If those who enact or support atrocities today want redemption, they can follow you.

If they don’t, they won’t.

And then you’ll know.

Question: redemption of what?

°

My religious tradition is Christian, as I think I’ve mentioned. Specifically, it is predominantly white sects of American Evangelical Christian, though as a missionary kid growing up in what was then Zaire, I may have, through no effort of my own, received a bit less direct radiation from the “American” and the “white” part of the whole thing than most … though perhaps I came a little nearer to direct colonial privilege than most, too. I guess what I’m saying is I may be unusual but I’m not special.

We have a lot to say about redemption, we Christians. You might say it’s our thing. As we have it, redemption is something that involves a cost paid—an impossible cost, in fact—that sets someone or something that had owed that cost free. So, I suppose, if I do the realigning and redeeming work of reparation, I should expect to find myself paying the cost of repair—whatever that cost might turn out to be—and I will find some measure of redemption for myself there, which will not only involve getting something but being freed from something. In my tradition, the way we put this is to say “to live, you must first die.”

I suppose the thing I’d be freed from is my blamelessness and my need to defend it with ignorance and complacency and denial and oppression and war. I suppose I’d be freed from the compulsion to prove my exceptionalism—with violence, if necessary—to anyone who won’t recognize it. I suppose I’d be freed from the compulsion to maintain a brokenness far more expensive than any cost of repair can ever be, and freed from the suppression and oppression I’d use to defend my choice to enforce an unsustainable world on everyone, including myself.

I suppose the redeeming work of alignment will mean I’m somebody who works at constantly entering a deeper awareness, a greater conviction, an easier confession, a more natural repentance, and a better and more lasting repair.

But … is that it?

Am I just doing this for the redemption of myself?

°

As I think I’ve mentioned at some point, predominantly white American Evangelical Christian churches have (institutionally speaking) served as the enthusiastic, joyful, energizing, sustaining, and organizing support system for the modern Republican Party. As for the Republican Party, I know I have mentioned it is observably a supremacist political operation—mostly white supremacist, to be sure, but you can find all the other supremacies in there as well, including Christian supremacy.

A hate group, in other words.

And I know a lot of white American Evangelical Christians. Most are really nice good kind people, and many are much nicer than me in many ways, and a bunch of them really have given their entire lives and careers to impacting the world in meaningful ways in ways I have not, in ways that truly do honor the best of our shared religious tradition, and many of them mean a great deal to me, and some of them don’t even support the hate group or the supremacist political movement the Republican Party represents with their votes or anything else, and many if they read these words would probably be genuinely sad that I’m saying these things that I find myself compelled to say because I believe they are true and important—and if they are sad, part of me at least is sad that they’re sad, because I don’t want them sad, and at least a part of me still hates to think of myself as the cause of their sadness.

And yet still, I must bear witness to the simple fact: the white American Evangelical Christian Church has become, institutionally speaking, the energizing, sustaining, organizing support system for a white supremacist organization, a political party that functions as a hate group; which runs on every form of bigotry, and which is presently driving us toward downfall and destruction and unsustainability on several different levels.

And at a certain point, you’ve joined what you’ve joined.

It’s a hell of thing.

What to do, what to do.

°

I’m going pretty hard at white American Evangelical Christians specifically, I know. This is in part because white Evangelicals really have proved themselves to be the sustaining lifeblood of this authoritarian supremacist movement, but also it’s my act of moral clarity. They’re where I’m situated, in ways I can’t extricate myself. I am Protestant-presenting, you could say. I’d have to do something dramatic to be seen as something else, and frankly I don’t have the wardrobe budget. But even if I did, I distrust the motives behind the impulse to separate myself. It feels self-defensive, self-aggrandizing, suggesting not a need to solve the problem but a need to be personally exonerated. It feels like the impulse to defend my own blamelessness, in other words. Moreover, white American Evangelical Christianity is the tradition that shaped me. I am as I am in large part because of it. They are a part of me, and always will be, to such an extent that my using the word they to talk about them doesn’t really seem as honest as we. But that’s where the witness and moral clarity come in, you see—since they are where I come from, I can implicate us with significant authority.

So let’s say it: I am a Christian. I am a white cisgendered heterosexual employed able-bodied well-off Christian. I am indeed a Husband Father Christian®, and could put that without lying in my social media bio, right next to my pronouns (which are he/him).

So that’s why I go so hard after my own religious tradition—because when we talk about our own failings we’re not just talking about our individual failings, but about the failings of our groups. These days that’s popularly understood to be the groups we vote with, but in truth the law doesn’t treat me as a Democratic voter, it treats me as a white able-bodied employed cis straight married Christian guy; a guy who is preferred, a guy whose life matters even though others don’t, a guy who checks the boxes, a guy who fits.

Which means I have to accept that when I talk about white American Evangelical Christianity, I am not talking about they, but we.

I’m part of this; I don’t get to choose about that. I just get to choose my alignment with it. Choosing my alignment for me personally means I don’t go to churches anymore; don’t lend my support or my money or the tacit approval of my presence to such an institution. And that’s cost me, in ways, and freed me in ways. But though I have separated myself physically, I won’t separate myself from them in terms of culpability and blame, because here’s the thing: in many practical ways, though they may try, they can’t separate themselves from me.

What reparation I do, I do on their behalf.

I am aware on their behalf.

I am convicted on their behalf.

I will confess the sins of white American Evangelical Christianity as a white American Evangelical Christian.

I will repent as one.

I will repair as one.

And then, maybe, I can help redeem something other than just myself.

To the best of my ability, I won’t help the institution from which I spring do the evil that it is doing in my country and the world, and I’ll witness to that evil as I see it, but even as I remove my support, I don’t remove my culpability. I’ll also lean into the moral complexity of finding myself there.

I won’t add to the crime if I can help it, but I’ll own the responsibility.

That strikes me as redemptive work.

°

I go after white American Evangelical Christians specifically for other reasons, too. Ironically, most of them are things I learned within that religious tradition. In my religious tradition (which again is Evangelical Christian), there is this fellow, a Jewish rabbi named Yeshua Ben Yosef (Mister Jesus if you’re nasty), and he’s sort of a big deal with my crowd.

So I guess I’d like to share some stories about Yeshua Ben Yosef.

Don’t worry. I’m not going to end this with a pulpit call (which, for those of you who don’t know, is a traditional invitation at the end of the sermon to come up front and profess belief in Jesus and become a Christian), I promise. It’s just that it helps me to use these stories to get at what I mean when I think about things like reparation and redemption. You may have your own tradition with similar notions. Please, use those instead. I wouldn’t want to use them here. I’d probably screw them up in my well-meaning ignorance.

Anyway, there was this Yeshua fellow, who was a Jewish rabbi as I believe I mentioned. We American Evangelical Christians are meant to listen to what he says, and we claim that we do what he says, which in my experience usually means we’ll give you our interpretation of what we have decided he said, which just so happens to match what we already wanted to do.

Examples? Examples.

One thing he said is that the pursuit of money is the root of all evil, and yikes most of us don’t like that one. I’m not a massive fan if you want to be honest. We have our interpretations of that one that lets us keep as much of our money as we can, and firmly control how the 10% we give away is spent so as not to disrupt our personal comfort and righteousness, to such a degree almost as if we’re not so much giving freely as buying righteousness.

He said that he came to set prisoners free, and we’ve got an interpretation of that one, too—one that lets us support a for-profit mass incarceration system, and the police and justice system that enforces and enacts it, and the lawmakers who set up laws to feed it, and even the most draconian punishments it can deliver, no matter how unjustly they are applied.

There’s another thing Yeshua said that I don’t think is very popular, at least in practice. It’s about getting the log out of your own eye before worrying about the speck in someone else’s eye. It’s a metaphor. I take it to mean “worry about your own failings before you worry about somebody else’s,” and it’s what I mean when I talk about moral clarity. We have an interpretation that takes it to operate on only an individual level, which is perhaps to be expected from a society that refuses to acknowledge anything collective. We also think it’s something that is very good for other people to do before they criticize us, but we seem to believe we’ve already done it ourselves and therefore see perfectly clearly—after all, we’re churchgoing Christians, the good people.

But never mind all that—these are all good teachings, and seem well-aligned with the work of reparation. I take no issue with them, other than that they are very difficult to actually do. I am nothing as good as the example Yeshua Ben Yosef sets, but I’d like to try to get near it, if I can.

It’s good to have role models.

Later this Jewish rabbi Yeshua (we’ve got a lot of stories about this guy) directly and materially challenged his own religious power structure, is how the story goes. And he also opposed the dominant economic, political, and military superpower of his day, too. And he managed to oppose both at the same time, by focusing on where the two intersected and supported one another. He did it pretty directly sometimes, and wickedly subversively other times, and frequently he used stories to totally reframe existing ways of doing things. He announced that he had come to repair what was broken and heal what was sick, and at one point he said he intended to restore literally everything, so I’d say he had a pretty ambitious reparation program in mind. But then he said that the people who followed him would be known because they would do even greater things than him, and by the way they loved one another, so he seemed to have big ambitions for his followers, too. And he was pretty big on loving people specifically by taking care of their material needs without worrying about whether or not they deserved it. It’s noticeable, if you read the book. I mean, he does it a lot. You’d think it would be unmissable to his followers today.

And they killed him—they being the dominant economic and military superpower of his day, which was the Roman Empire. It wasn’t the Holy Roman Empire yet, because it hadn’t yet made itself Holy yet, which it accomplished by making itself the power-center of a religion dedicated to the Jewish rabbi they had murdered, and began to revere him without ceasing to be the thing that had killed him, which, again, was a dominant economic and military superpower. This strikes me as a pretty good example of blameless supremacy.

Anyway, before the Roman Empire decided Yeshua was their God, they killed him. If you’re a student of history you’ll perhaps recognize that’s how opposing the dominant economic and military superpower of your day often goes. And now Christians represent the dominant economic and military superpower of our day, and demand a position of privilege within that superpower, which is just something I thought I’d mention for no particular reason.

As our Christian tradition has it, in that moment of dying Yeshua redeemed the entire world, specifically by paying a price that nobody else was willing or able to pay, and this actually allowed him to achieve a redemption that conquered death itself. Yeshua paid a cost that was intrinsic and inherited, automatic and inextricable—the exact type of burden I can’t help but notice most conservatives, particularly most white conservative Christians, categorically refuse today when asked to shoulder it, because they insist that they are blameless, which is exactly what they also say Yeshua was when he shouldered a much larger burden.

So much for role models, I guess.

In the story, Yeshua predicts this death will happen, and then says that it will be a redemptive act; that it would, in fact, remake the world.

Fair to say Yeshua understood the idea that redemption involves paying costs.

I think if white conservative Christians are truly interested in redemption, then the good news is, the path has been walked for them already.

If they want redemption they’ll follow.

If they don’t, they won’t.

And then we’ll know.

The Reframe is me, A.R. Moxon, an independent writer. Some readers voluntarily support my work with a paid subscription. They pay what they want—more than the nothing they have to pay. It really helps.

If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any future books.

I am nowhere close to being as good as Yeshua Ben Yosef is in the stories, but I’d like to try to be like that a bit. I’d rather not be tortured to death, and I hope that’s OK with you—but as I said, it’s good to have role models. Anyway, that’s why I oppose my own religious tradition, precisely where it intersects with the dominant political and military superpower of its day.

Yeshua was Jewish, as I believe I mentioned.

We follow Yeshua, we Christians. Yet we’re not Jewish. There are dogmas that explains this, with scriptures to support it. Ask any Christian and they’ll surely unpack it for you, but still sometimes that’s weird to think about, that we all follow Yeshua but we don’t belong to his religious tradition. I also think it would be weird if all followers of Yeshua decided to become Jewish, and I have this instinct that such a mass conversion would probably not be the sort of thing that Jewish people would generally want or appreciate.

However, we Christians worship a Jewish rabbi, yet we aren’t Jewish, and I think about that a lot.

I don’t know of any Christian explanatory dogmas that don’t negotiate away Judaism to some degree, and frankly I’m not very comfortable with those dogmas anymore, simply because I am not comfortable at all with any urge to negotiate Judaism away. Even if I wasn’t a Christian, it would seem to me to traffic in antisemitism, but as somebody who claims to follow a Jewish rabbi, negotiating away that rabbi’s religion seems bizarre. (I’m pretty sure this is all heresy to most Christians, by the way, in a way that becoming a billionaire, or voting for a white supremacist fascist would-be dictator is not. Sorry for all the heresy, Christians. I’m just sort of thinking out loud here.)

It makes me ask myself: did this Jewish rabbi engage in this work of reparation, and this self-sacrifice, just to start another religion among other religions, or even a religion over other religions? To start a religion that is particularly self-aggrandizing and self-promoting, that apparently expects the whole world not so much to follow its example as bend to its will?

Did the Prince of Peace arrive to convince his followers to dominate?

It seems more likely to me that what Yeshua was doing was something that transcends religion in a way; something that enters the world more like a new spirit moving people into an awareness of something that was always true. A new story that would change the atmosphere, in other words, not a new religion that would conquer the world. A story about a universe that reveals itself to the awareness it has nurtured and created, not as power but as sacrifice, not as danger but as safety, not as complacency but as love, not as distant and remote but as present in every instance. About the universe providing an example to the awareness it has created: that those who have least deserve most consideration, that to live well in the world is to care for the needs of others and that the best use of power is to give it away to those without, with no thought of whether it is deserved.

By the way, this seems the more likely motivation to me because that’s what it seems to me Yeshua actually said he was doing.

What to do, what to do.

°

Let’s end with a few more stories.

Yeshua told another story once, about father who owned a vineyard and told both sons to work in it. One son said he would, but didn’t. The other son said he wouldn’t, but did. Then Yeshua told the gathered religious leaders that the tax collectors and the sex workers were entering the kingdom of heaven ahead of them. Try that one sometime on a Sunday.

He followed it up with a story about another father who owned a vineyard, who gave it to some tenants to take care of it while he was away, but the tenants became murderers and thieves who refused to produce the fruit of the vineyard. Yeshua then announced that the father would return and take the vineyard away from the tenants it had been given to, and give it to others, who would produce its fruit.

Fruit strikes me as a powerful metaphor, because fruit is observable, and undeniable, and nutritious and sustaining. People can taste it. People can live from it. Also, fruit happens naturally, but to reach the fullness of its potential, it requires cultivation.

If people can’t live from it, then it isn’t fruit.

If it kills and harms and steals, then it isn’t fruit.

And Yeshua Ben Yosef says that if people don’t do the work and pay the costs, then the means of producing fruit will at some point be taken away, and given to a people who will produce its fruit—and remember that right before that, he had announced that the moment had already come; that the means of fruit had already been taken away from those who claimed to cultivate it but refused to do the work even though they say the proper things, and given to the people who were doing the work of cultivating it, even if they don’t say the expected and proper things.

The purpose of a vineyard is to produce fruit.

So what’s done with an unused vineyard? It’s taken away from those to whom it has been given, and given to the people who will produce its fruit.

Hm. Now, that’s a good idea.

Go do that.

Take the vineyard away from Christians—from us Christians. Give it to people who will produce the fruit of reparation by doing the work of repair.

I’m serious.

I promise this isn’t a pulpit call.

Do it without becoming Christians.

Take the vineyard of reparation and redemption that white conservative Evangelical Christians claim as their exclusive property, which most aren’t even using, and give it to the tax collectors and the sex workers, who are producing its fruit. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say: demonstrate the spirit by enacting the part of the church’s story we white American Christians refuse to enact. Redeem the story we white American Christians have scorned even as we flatter ourselves in the telling of it. Redeem the spirit we white American Christians claim is for the world but which we horde for ourselves.

I want to be very clear what I’m proposing here. I’m not asking you to become Christians. I’m not asking you to take on Christian doctrine or practice. I’m not asking you to join a Christian church. In fact, if you don’t belong to a church, don’t do that. If you are a Christian, stay if it helps, but perhaps consider whether that’s the best way to cultivate reparation’s fruit before staying.

You may be an atheist. If you are, I want you to stay an atheist—an atheist that does the realigning work of reparation and redemption. You know what that is? That’s an unused spirit of redemption being taken away from a people that claim it as its sole property, and giving to the atheists, who will produce its fruit, and the same with the drag queens and the sex workers, and the trans and nonbinary people, who will produce its fruit, and to the undocumented immigrants and fugitives, who will produce its fruit, and of prisoners, who will produce its fruit, and of Black Lives Matter activists, who will produce its fruit, and of local community organizers of mutual aide funds and bail bond funds, who will produce its fruit.

You may belong to other religions. Please, stay that way. As long as you are doing the realigning work of reparation and redemption which I am sure you can find within that tradition, you will be taking a spirit of redemption away from people who claim to possess it as their sole property—though they refuse to produce its fruit when it threatens their exceptionalism, their blamelessness, or their supremacy. Take it wherever you find it—even from the Christian tradition, if you happen to still find it there. Take redemption away from those who refuse to do redemption’s work, which is reparation, and produce reparation’s fruit.

We don’t need to form some new institution to defend. Stay where you are. Enter the spirit of an expansive, open, diverse, and vital movement that was never the exclusive property of Christians anyway, a movement that would be worth joining, if only it existed, guided by a spirit that is worth celebrating and defending and joining, everywhere it already exists.

If enough people do that, then before you know it, such a movement would exist, and we might not even need a religion we’d call Christianity anymore.

And for people who worship a man who died so that the world could live, letting Christianity die so that the world might have abundant life might seem like a very Christian goal.

Speaking as a Christian, I am not sure that “Christianity” is what we should be working for.

Changing the atmosphere is what we should want.

Repair is what we ought to be after.

The spirit is the thing.

°

We’ve been talking about the redemption of Christianity, but that’s just because for me it’s the closest thing at hand. We could be talking about the redemption of many things.

We could talk about redemption of the United States of America—a country that claims to be founded on principles of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, a country that claims to provide liberty and justice for all, a country that actually was founded on supremacy and genocide and slavery.

For such a country to become what it claims to be in its founding documents, it would first have to be aware of what it is, convicted of the need to change, willing to confess that need publicly, able to realign itself away from what it is and toward its finest ideals, and then actually do the work of the journey.

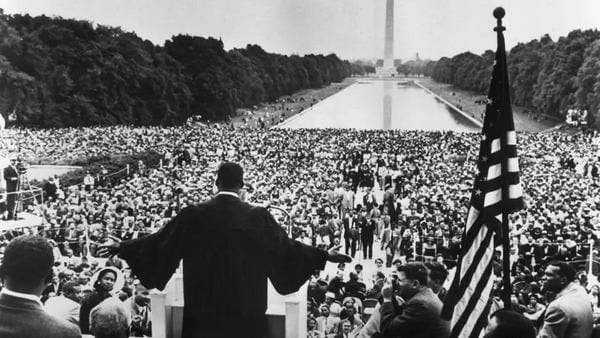

Martin Luther King Jr. comes up frequently. He was a Christian, which is something I think Christians can be proud of, if they are willing to enter the same spirit he entered. King was very much in the tradition of Rabbi Yeshua Ben Yosef, in that he too opposed his own religious power structure, and the dominant economic, political, and military superpower of his day. And he managed to oppose both at the same time, by focusing on where the two intersected and supported one another. He did it pretty directly sometimes, and wickedly subversively other times, and frequently he used stories to totally reframe existing patterns of belief.

He gave a famous speech about a dream he had, of a country where those things had been made true—which is the popular and much-repeated part of the speech. The main theme of the speech was of all the ways the dream had not been made true, and the unsustainability of that injustice, and the inevitability of strife and unrest until justice breaks free, and the need to do the work of repair—which is less popular, and less often repeated.

King’s speech ended like this:

And this will be the day – this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

My country ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing.

Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring!

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!

Wow. Coming from somebody who most of white America considered at the time to be a lawbreaking rabble-rousing anti-American socialist, that sounds downright patriotic.

Wait. Am I asking you to be patriots?

Not exactly. But … maybe?

Maybe let’s be patriots of a country that doesn’t exist yet; a country where all those fine aspirations have been cultivated until they are, at last, and for the first time, actually true, in a way that is undeniable because the fruit of it is all around, sustaining everyone without any question of deserve. And then let’s enter a spirit that is willing to do the work to make it so, and not finish until that country is the country we see all around us.

Maybe we can redeem our broken institutions and our broken nation, on behalf of everyone—even those Very Fine People who are violently aligned against redemption.

You know what that would be? That would be taking patriotism away from the patriots, and giving it to the people who will produce its fruit.

A lot of Very Fine People would have it that King only gave one popular part of that one speech, but he gave many others. The last of them is known as the Mountaintop speech, and it was delivered in Memphis in solidarity with striking workers there. In it he spoke of the work of repair that was needed and the unsustainability of any land that refused to do it, and he spoke of the inevitable strife that would attend that unsustainability.

He talked about going to the mountaintop, which was a picture from the Bible, from what Christians call the Old Testament and Jews call the Torah—of Moses, the leader of Israel, a nation of freed slaves, watching from the mountain at the end of his life as the people he had led entered their land.

I like that; the idea of ending a speech about necessary work with a picture of arriving at the top of a mountain. Climbing a mountain certainly takes a lot of intentional work, and provides an amazing view that would be unavailable to anyone who didn’t do that work.

Yes, I like that picture very much.

Less than 24 hours later, King was dead; as dead as the dominant economic and military superpower of his age had hoped he would become. If you recall, that is how opposing dominant economic military superpowers tends to go.

And many Very Fine People rejoiced on that day of mourning.

King may have climbed to the mountaintop, but white America hadn’t.

They had been offered the realigning work of redemption, and had declined.

They still do.

They? We.

We? I.

What’s being said isn’t that white America is irredeemably bad. What’s being stated is an old truth, which is that white America has proved remarkably unwilling to do any of the work of redemption, because it would cost them not only their money, but their exceptionalism, their blamelessness, their position as the chosen elect. The reaction of white America to this truth whenever this truth is spoken aloud suggests it is an ongoing unwillingness.

Or, let’s put it this way: White America seems very happy to claim they live in Martin Luther King Jr’s dream. It seems totally unwilling to climb his mountain.

But I think we can begin to enter King’s spirit, if you start to climb.

So let’s take the United States away from those who scorn all its finest ambitions and ideals, and be the kind of people who will produce its fruit.

In doing so, we’ll redeem our broken natural human system, not just for those who deserve it, but for those who don’t.

We’re talking about white America. We could be talking about straight America, or cis-het America, or able-bodied America, male America, Christian America. We don’t even have to be talking about America. We could be talking about many places, and many things.

°

Whose redemption did you think we were working for? Our own?

I don’t know. Seems to me as if redemption isn’t a prize to be won, but a price that needs to be paid, maybe a high one, by many of us, including ourselves.

I think we need to be willing to work in the vineyard. I think we need to do the work of redemption without expectation of receiving redemption in return, and let reparation’s fruit be its own reward.

We may as well. It’s only once we’ve done that would we truly be able to receive redemption, even if somebody tried to give it to us, for the simple reason that blamelessness can’t accept the premise that it needs redemption. Maybe if what we want is forgiveness we need to stop forgiving ourselves and do something redemptive, so that other people can have a bit of room to forgive us instead.

So: do the work of redemption, so you have that gift to give. Then: give the gift of redemption, and you might even someday receive it yourself.

Go and find your willingness. I hope to go with you. If you don’t see me, look behind you; I’ve always been a little slower than average. I may be lagging.

Do the realigning work of redemption. We’ll know the cost when we start to pay. Set your compass and follow it back home. We’ll know we’ve arrived when we get there.

Tell stories that move the frame.

Align with new ideas and very old ones.

Change the atmosphere.

Release your blamelessness, embrace endless improvement.

Stop being Very Fine People. Become what you are, which is art.

Redeem the brokenness you can, and hope to become redeemed yourself.

Change your spirit, and change your alignment, and then watch our atmosphere change.

°

The spirit is the thing.

directions.

The Reframe is totally free, supported voluntarily by its readership.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any books I publish.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the essay collection Very Fine People. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He wants a shoehorn; the kind with teeth.

Comments ()