The National Current

The benefit of the doubt, the doubt of the benefit, and presidential precedent in a country allergic to truth and consequences.

Well, the White Christian President got hit with 37 counts of federal crime this week, which, as counts of federal crime go, seems to me like a lot of federal crimes—for a presidential candidate, anyway.

What did he do? Oh boy! He took nuclear and other secrets acquired from his old job, and he shoved them into banker’s boxes that he stored in his somehow-simultaneously-gaudy-yet-squalid bathroom and other places, and he travelled around with them, and he showed them around to various people to impress them with what a big shot he was, and he obstructed all attempts by federal agencies to retrieve them, and there is damning evidence that he did all this in full knowledge that he was breaking some rather serious laws, and endangering groups of people like “intelligence agents” and “soldiers” and “all of us.” Oh, and some of the most sensitive documents are missing, and whoopsie-poopsie, turns out all of this is very illegal—which it seems to me it ought to be. And now, because he did crimes, the White Christian President will face a trial—which seems to me the way the legal system ought to work. If he’s convicted, I guess he’d go to prison, and while I’m big on prison reform, I’d say if there was ever a person for whom a prison would make sense as a destination, it would be a career criminal who has very likely committed many acts of possible espionage, and who tried to overthrow the U.S. government, which is something the White Christian President has definitely done.

And he’s already been charged in New York for illegally falsifying business records after illegally paying out hush money from campaign funds in order to cover up one of his extramarital affairs. And he’ll probably be facing charges in Georgia soon for conspiring to overthrow the last presidential election, which is something we all watched him do with the mob he sent to murder Congress on January 6, 2021, but we also know he tried to tamper with the election through other channels as well, leaning on election officials to throw out ballots or find new ballots and whatnot. And he was recently found liable in civil court for battery and sexual assault, which are crimes. And there are many other crimes he committed as well, some of which I believe he’s under investigation for and others of which—like using the office of the presidency to enrich his private business—he was simply allowed to do without consequence, making that previously unprecedented act something very precedented indeed.

Anyway, the White Christian President is observably an abusive and corrupt criminal, yet all of this just seems to make him more and more popular with Republican voters and Republican politicians, even the ones who are running against him for president, all of whom came to the defense of the boss whose job they hope to gain without actually ever fighting him for it. So we’ve been treated to the nauseating spectacle of Kevin McCarthy and Ted Cruz and Ron DeSantis and Vivek Ramaswamy and even Mike “Mommy” Pence (who Trump tried to assassinate via mob a couple years back), all lining up to decry the Justice Department, an agency that is tasked with investigating and prosecuting federal crimes, for …. investigating and prosecuting federal crimes, an apparently unprecedented thing for it to have done. And many of these denouncements of the Justice Department’s pursuit of justice have been accompanied by veiled or not-so-veiled threats of retaliation and retribution, some of them political, and some of them violent, but none of them distinguishing the Republican Party’s elected officials from, for example, the version of the New Jersy mob that we all enjoyed watching on HBO’s The Sopranos.

All this pretty clearly (and yet again) exposes the Republican Party as a criminal organization, supported by a supremacist movement that’s perfectly comfortable with corruption and crime and abuse and political retribution and incitement to violence, provided all the crime and abuse benefits the right people, or at least hurts the people who they believe ought to be hurt.

You’d think the Republican Party being exposed as an open criminal organization with supremacist leanings would be viewed as a problem for Donald Trump and Republicans, and to a degree, I suppose it is—after all, Trump will have to plead guilty or face trial, and the Republican Party will have to explain again and again why the man who will almost certainly be their candidate may very likely be heading to white-collar-tennis-court prison.

So yes, practically speaking, these crimes are a problem for the perpetrators.

But I know I’m not the only person who has noticed that the national current runs in the opposite direction.

If you ask a large section of our media, for example, the leader of the Republican Party facing trial for 37 federal crimes is a big problem for everybody except Donald Trump and Republicans. The instinctive and automatic response to the Republican Party being led by a flagrant criminal is pretty much the same instinctive and automatic response to everything else that attends the Republican Party being an open and enthusiastic supremacist fascist and anti-democracy hate group, which is to frame as normal any previously unprecedented thing that they do, and to frame as problematically biased anyone who treats all of this unacceptable and dangerous and harmful behavior as unacceptable and dangerous and harmful.

I’d say this is how unprecedented things so quickly become precedented these days.

We just keep looking forward, not back, mostly so we won’t have to see all the things we’re leaving behind in the rearview mirror, things like millions of victims, and fair and free elections, and free speech, and a woman’s right to receive basic reproductive healthcare without facing prosecution. And torture is a thing that’s been openly on the table for decades now. And you can engage in a misinformation campaign to lie a country into war and a decade later many of the same people who opposed you will talk about how they miss you, and how heartwarming it is that you’re so chummy with the First Lady, and they’ll run puff pieces on your painting hobby. And Presidents can use their office to make huge profits for their hotel chains. And so on.

Refusing to look backward is almost always framed as unifying and positive, while looking backward and reporting on what we see is almost always framed as divisive and negative. We’re not interested in unity with victims, it seems. Unity is a gift we save for the perpetrators.

Apparently prosecuting a flagrantly criminal ex-president and current presidential candidate is dangerous, and inherently political, and unprecedented, in ways that running a criminal as a candidate for president isn’t.

Apparently talking about the Republican Party accurately as an anti-democracy fascist criminal organization would be far more biased than pretending that an anti-democracy fascist criminal organization is still a viable political party interested in participating in the governance of the country.

Apparently, a White Christian President’s crimes do not corrode the rule of law, but using due process to charge him with crimes and giving him his day in court will demolish it entirely.

Apparently, giving a White Christian President his day in court represents destabilizing political retaliation, while threatening political retaliation in response to due process is a normal and expected reaction for members of the White Christian Party to have.

So the cases for automatic exoneration come pouring in, even from non-Republican operatives: the idea that Trump’s criminality is a problem mostly for Biden, that what ought to happen to restore stability is not to remove the criminal element from our government, but for the opposition to just let bygones be bygones in the interest of unity, and issue Trump a blanket pardon, as long as he will just promise not to run—as if Trump has ever shown himself trustworthy in the matter of promises, as if maintaining our national addiction to looking-forward-not-backward will result in anything other than a continuance of what it has already resulted in, which is a string of national leaders whose corruptions and abuses grow more flagrant and overt and proud and bold, stringing out new links in a never-ending chain of new and worse precedents for what is acceptable for conservative leaders to do, as the bodies in the rearview pile up into a mountain that requires more and more discipline to avoid seeing.

All of it rests on an unspoken foundational bedrock, which is that Trump is rich and white and powerful and conservative, and our systems of justice and consequence—which can destroy the life of somebody who doesn’t fit that bill so instinctively and casually they often will do so without even knowing they have done so—is so terrified of issuing any kind of consequence to someone who does fit that bill, that it proceeds with exceeding caution, a cringing and apologetic sort of trepidation verging on fear, a congesting allergy to truth and consequences.

It’s an acknowledgement, made without even the intention to do so, of who counts and who doesn’t.

The White Christian President counts.

The people who he has harmed and killed do not, nor do those he will harm and kill in the future if he isn’t stopped.

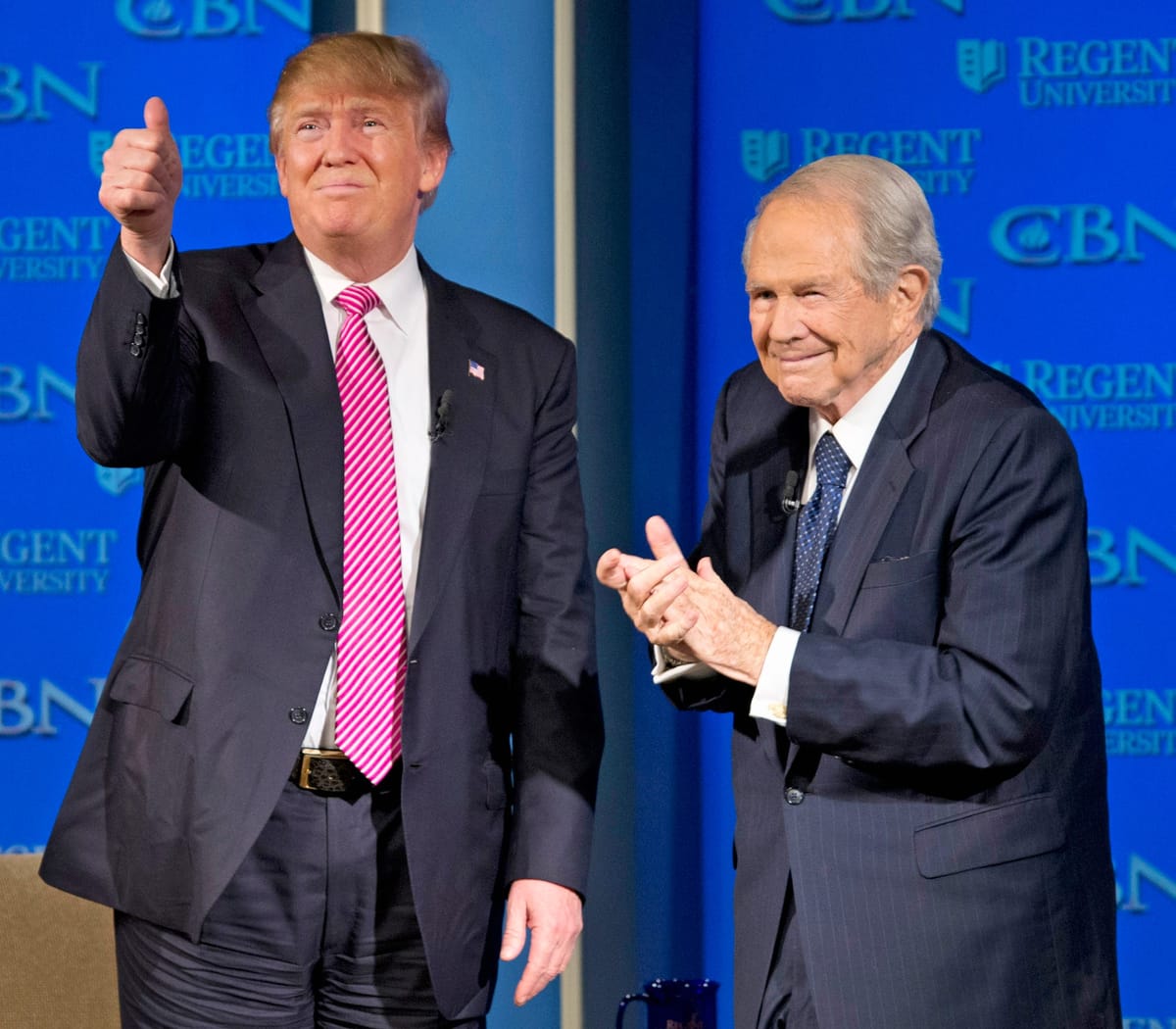

To digress somewhat: as White Christian President was being charged for his 37 federal crimes, Pat Robertson died, which is one of the best things he’s ever done.

In case you don’t know, Robertson was a permanently elderly gnomish televangelist kept alive for decades by pure living and even purer hate, and he is the reason your sainted granny spent her final decades falling into a far-right reactionary supremacist cult, or at least he’s the reason mine did. He’s a turd of magnificent size, in other words, and I’d like to briefly express my relief before I flush.

Robertson rather famously never let a tragedy pass by without hopping onto the TV to point out that the latest tragedy was God’s wrath on the country for not being an authoritarian theocracy, or God’s righteous vengeance upon the nation for failing to become a perfected example of white christian supremacism—a failure which mostly involved letting women be recognized as human beings under the law and permitting gay people to exist, and so on. He’s one of the people most responsible for white christianity’s unholy marriage to far-right politics, and for there even being such a thing as a White Christian President in the first place, and if you wish we lived in a world where the Christian church in America wasn’t the energizing and organizing movement behind a white supremacist political organization, if you wish we lived in a world where so many of our friends and family hadn’t been completely lost to a national supremacist hate cult, there are only a few people you can blame more for that particular state of affairs than Pat Robertson, who lived a life worth mourning.

And with his passing, we had the usual discourse that attend the passing of a serial abuser. Some people spoke of Robertson for what he was, which was a sort of spiritual kidney stone, and of the horrible things he had made a career of saying, and his contributions to demonization and harm of marginalized people, and his outsized role in creating a supremacist far-right vision for the nation and marrying it to a religion for which such things ought to have been antithetical. And they spoke of their relief at his passing, which is an appropriate way to talk about a kidney stone of any size.

And on the other hand, the usual voices remonstrated against this outpouring of truth, scolding how inappropriate it was to use the passing of a toxic man to discuss how toxic he had been, even though it seems to me that even if you think Robertson’s death is tragic, the most appropriate way to honor the legacy of a such a man would be to frame the tragedy as God’s righteous judgement upon those who suffer from it. Maybe God decided he liked gay people after all, and that’s why he killed Pat Robertson; at the very least saying so certainly fits Pat Robertson’s definition of what would be an appropriate thing to say when people have died.

It seems that for a lot of people, there is a danger in letting an abuser’s abuse be remembered for what it was; something more troublingly unseemly about acknowledging abuse as it ends that doesn’t apply to its long decades of approved continuance.

It seems that on a fundamental level, those who mourn the passing of an abuser count, and those who were forced by his abuse to mourn his life do not.

I think it speaks less to a desire for decency and more the ways we would like to remember indecency. Or, more accurately, the way we’d rather forget it.

This is seemingly instinctive and automatic, like an allergic response: a rhetorical sneeze expelling consequence for abuse from the national system like ragweed pollen.

It’s unmissable, once you’ve seen it.

It’s also completely invisible, if you don’t want to see it.

Not seeing it is treated as normal—precedented—in a way that seeing it is not.

It rarely seems to be the crime or the abuse or the corruption that’s treated as unprecedented, even when it happens on an unprecedented level or in an unprecedented way. Crime and corruption committed by power and wealth appears to be pretty normal and expected, actually; at the least, it is easily digestible. That stuff can be treated as alarming, but treating it as unprecedented would constitute a consequence, if only a rhetorical one—and it’s consequence for abusive power that’s truly unprecedented.

Just dip your hand in the nearest available information stream and you’ll notice that the national current runs toward impunity for certain kinds of people—specifically, for abusive and powerful and wealthy people—for whom the benefit of the doubt must always be seen as indestructible, whose good intentions and better angels must always be celebrated even if those good intentions and better angels first have to be completely invented, for whom consequence must always be seen as a greater adverse disruption and a more present danger than continued enablement of their increasingly unprecedented and empowered self-enriching abuse ever could be.

We live in a world that appears to be set up to let them get away with it.

I say this because the loudest alarms get saved for the moments when it seems possible they might not get away with it. That is the moment of danger for our society, it seems.

And again, this is as submerged and as powerful as a current, as seemingly instinctive, automatic, and unstoppable as an allergic reaction, this aversion to truth and consequence for certain people who we all know, even if we don’t tell ourselves we know, are supposed to get away with it, no matter what it is.

Where will it all stop? seems to be the question most often asked whenever consequence in any form seems likely for empowered abusers, which seems to me to be a question somebody asks about abuse when they don’t want it to stop; when they don’t want anyone asking how do we make it stop?

The most dominant voices in our discourse seem to fear a reversal of our national current, and it seems likely to me this is because, in a hypothetical world where the current flows to protect victims rather than perpetrators, they perceive some danger of consequence for themselves—even if they are not powerful or wealthy, even if their own abuse wouldn’t enjoy similar impunity, even if they are themselves often suffering the harmful effects of empowered corrupt abuse.

But … for those who don’t enjoy the same impunity … what consequence would they experience if that impunity were finally rescinded?

Like most everything else, I think the answer can be found the TV show LOST, which I’ve been exegeting at length for the last year or so.

I think I’d better address new things I’ve learned about LOST before I continue.

That’s right, Egon: I’m crossing the streams.

But I’ll think I’ll save that for next week.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and is co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He’s thinkin’ about his doorbell, when you gonna ring it, when you gonna ring it.

Comments ()