The Unmovable Sink

How do you make impossible things possible? Same way anyone ever did: By trying.

There's a movie that came out about 50 years ago, which makes it quite old but not quite as old as me. We would have gone to high school together, though, me and this movie, if movies went to high school. It was called One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and according to Wikipedia it's still called that. The movie is based on the play that is based on Merry Prankster founder Ken Kesey's countercultural novel of the same name, and it starred Jack Nicholson and Louise Fletcher, and Danny DeVito and Christopher Lloyd and Scatman Crothers and Brad Dourif, too, and many others. It was very popular and I think it still is; it won all the Oscars that year and it still shows up on lists of great movies and all that. You can go watch it if you want to; nothing can stop you. I haven't seen it since the 1900s, when I was a bit younger and so was the movie. I don't remember everything about it. Does it hold up? Maybe so. Many movies do. Maybe I'll watch it today and find out.

Whether it holds up or not doesn't matter for today's purposes. There's an idea from the film that stuck with me that I'd like to share with you today, generated from two scenes.

In the first scene, incarcerated psych patient Randle Patrick McMurphy is pushing back against authority, as protagonists of countercultural novels tend to do. McMurphy is a live wire on a floor of wet noodles; they've all given into The Man, man, by taking their meds and sticking to hospital policy and schedules and all that. (If I seem a little sarcastic, I suppose it's because I've grown leery in recent days of people who express their countercultural bona fides by refusing to listen to medical professionals. I should probably let this point go; if I recall correctly, the movie is making a different point unrelated to psychiatric care, and I believe the hospital setting is meant to be largely symbolic, because while psychiatric incarceration is a common tool of autocratic governments to control political dissidents, that isn't what's happening in this movie. Only one of the inmates might be incarcerated for what could be political reasons, and—with the possible exception of McMurphy—all are depicted as having mental illness. Instead of letting it go, though, I wrote this long parenthetical. Oh boy!)

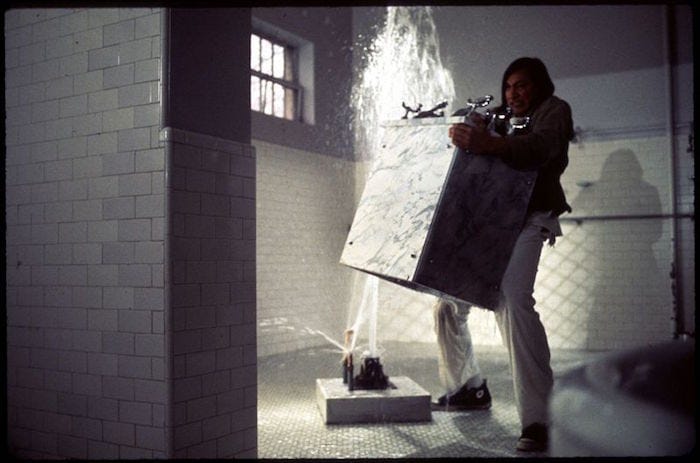

McMurphy wants to go to a bar and watch the World Series on television. The other patients point out that this is not possible, given their incarceration. So McMurphy makes them a bet: He will break out by lifting the huge industrial sink connected to the middle of the ward floor, and throwing it out the window. Beer and baseball await. Nobody thinks McMurphy can do it. McMurphy insists he not only can, but will.

He fails, of course. He's just not big enough. He doesn't have the leverage. He doesn't have the strength.

"But I tried, goddammit, didn't I?" McMurphy asks them, glowering. "At least I did that."

Some weeks and months later in the world of the movie, we get the final scene, because it is time for the movie to end. One of the inmates who was present during the first scene decides it is time to break out of the institution. This inmate is a Native American gentleman named Chief Bromden. Bromden has been a silent presence throughout the events we've seen; an immense man, mute by choice (in the novel, Bromden is the narrator, and his ethnic identity marks him as the one inmate whose incarceration might be at least partially political). Bromden has the strength, the size, and the leverage that McMurphy lacked. He lifts the sink, and throws it through the window, and off Bromden goes, into the surrounding forest.

Would Bromden have thought to lift the sink, if McMurphy hadn't suggested it, if McMurphy hadn't tried first? Maybe so, but I think not. The movie seems to think not. So does the book, if memory serves. I never saw the play.

I take several things from the sequential progression found in these two scenes. One takeaway is the idea that even unmovable sinks are movable; once somebody introduces the idea of moving it, what's impossible can suddenly become possible. This suggests that it is very powerful to believe in the possibility of impossible things. Another takeaway for me is that people tend to be poor judges of what is possible, and mostly tend to cede to others the parameters within which possibility can be pursued. This suggests that it is very important to take control of the boundaries of the possible, because doing so expands those boundaries. Another takeaway for me is that efforts that fail at first—even efforts that are doomed to fail at first—are not wasted efforts; especially not if the sink really needs to be moved. This suggests that if we really believe in the necessity of something, we should consider even the effort to achieve it to be a victory—not a moral victory, but an actual victory, because it is exactly this effort that brings victory out of the realm of the impossible and into the realm of the possible.

I think about it these days, because we've got an unmovable sink called supremacy, and a lot of people have decided that the best way to deal with it is to make sure we don't waste any effort moving it—not because it doesn't need to be moved, but because many people would rather avoid any effort.

There are a lot of ways to not move the sink. All you need is a reason, and any reason will do.

There's only one way to move it, and that's by trying.

Please forgive this brief interruption.

Maybe you've noticed that it's getting harder to truly know what's going on these days. Legacy media—controlled by corrupt billionaires and addicted to the false equivalency of balance rather than dedicated to the principle of truth—has failed us. I am recommending that if you have money to do so, you donate and subscribe to independent sources of information instead. This week I'm suggesting you support your nearest alt weekly. As Radley Balko says, "alt weeklies have a storied history of breaking big stories long before daily newspapers catch on (and then report and take credit for them). They’ve also been proving grounds for excellent journalists who may have not had the connections to break into the profession."

We now return you to the essay in progress.

Our country has moved the supremacist sink before. We had a president once who was determined to face down a murderous and supremacist confederacy, a traitorous movement so dedicated to supremacy that it waged war against its own citizens in order to protect their white supremacy and the vile practice of human enslavement that grew from it. That president was so determined to defeat this confederacy that he met it in the war it had started against its own nation; waged war against those murderous white supremacist traitors, and used their moment of abandonment of government to push through proclamations and legislation and Constitutional amendments that disabled much of our country's foundational genocidal industry of human enslavement. This act was seen as extreme and extremist, but it moved the sink of supremacy—not out the window forever where it belongs, but a significant movement all the same.

Incidentally, disabling the institution of human enslavement was something that a group of massively unpopular and hated and brave people called abolitionists had been demanding for years and decades prior, long before it was a likely outcome, back when the abolitionist demand was seen as violent and extreme in a way that the horrific genocidal violence of human enslavement was not; back when reasonable practical people insisted it was a terrible idea, impractical, divisive, polarizing, and impossible, impossible, totally impossible. So impossible, in fact, that many who claimed to oppose slavery opposed abolitionists, scolded them for making the abolishment of slavery unlikely, which it was ... until it happened.

At another time, a mass popular movement of extraordinarily brave and determined Black citizens engaged a movement for universal civil rights, a movement based on basic human truths. In the end, they created enough pressure upon various governing institutions and organizations and office holders that legislation was passed that disabled much of supremacy's newest expression—an apartheid-state regime of segregation of Black citizens from white citizens enforced by murderous political terrorism called Jim Crow. The Civil Rights Movement moved the sink of supremacy—not out the window where it belongs, but a significant movement all the same. It was something that a group of massively unpopular and hated people called civil rights activists had been demanding for years and decades prior, long before it was likely, back when the demand for universal human suffrage was seen as violent and extreme in a way that Jim Crow's murder and theft and terror was not, back when civil rights was a terrible idea, impractical, divisive, polarizing, and impossible, impossible, totally impossible. So impossible, in fact, that those who claimed to oppose Jim Crow opposed the civil rights movement, and scolded its adherents for making the securing of universal civil rights less likely ... right up until they were secured, that is.

There are people still alive who fought and demonstrated and saw their friends die in order to move that sink. More to the point, there are people still alive who fought and demonstrated and killed in order to protect that vile institution, and their ancestors both actual and spiritual are fighting and demonstrating and killing to re-establish and retrench segregation and political terrorism of white people against Black people, and of straight people against queer people, and of rich people against poor people, of men against women, and so on.

Supremacists in the Republican Party are moving the supremacist sink back to its originalist spot right now, dragging it back across the floor, reconnecting the pipes of apartheid and segregation and slavery, doing things many comfortable people had thought sure was impossible, and then they intend to bolt it to the floor. They're openly talking about a third term for their dictator. They're sabotaging and demolishing our shared society so they can ensure that whatever is left, however diminished, will at least not be shared. How did they do it? Same way it got moved in the first place.

By trying.

One must admit that American conservatives have truly proved themselves committed to white supremacy, male supremacy, and all other expressions of supremacist hatred and bigotry. They really truly do believe in the natural right of white property-owning christian men to dominate and possess everything and everybody else, and to punish and harm and menace and murder anyone who doesn't comply. After the Civil Rights Movement enjoyed its gains, and the sink had been moved toward the window, they looked at their position, and the general popular and institutional opposition to moving it back, and they went about moving it back anyway.

It was impossible—at first. Those previous expressions of supremacy had stopped being popular, mostly. It wasn't polite to be a member of the KKK, or a white supremacist organization, or a Nazi movement, or to say the sorts of things that white supremacists, KKK members, or Nazis said, or to want to do the sorts of things that they do; segregation and christian nationalism, for example.

Being a white supremacist is mainstream now. To be a Republican these days means believing wholesale in the entire white supremacist/Nazi belief system, or perhaps we could say in the belief system of the KKK and foundational American supremacy that inspired the Nazis. All the usual nativist claptrap is in place—the celebration of a national myth of cultural and racial purity, the vile replacement myth that forms the spin of antisemitic belief, the vilification and demonization of marginalized groups, the loyalty to an authoritarian strongman, the eugenicist view of women as breeding stock owned by men, of the disabled and elderly as "useless eaters," the anti-intellectualism and attacks on colleges and journalists, the patriotic celebration of domestic authoritarian horror and military adventurism, and so forth and so on. They're even doing little sieg heils on stage now—as a joke, many say, although the joke appears to be "we can get away with sieg heils now." In mainstream conservatism the Nazi/supremacist value-set is popular—so popular that those who don't personally believe in one part of it or another keep their mouths shut if they know what's good for them. And it took decades, but supremacy has indeed moved the unmovable sink.

A lot of very comfortable people watched them move the sink, inch by inch, foot by foot, assuring themselves that the sink was not moving because moving that sink—overturning abortion rights, capturing the Supreme Court, ignoring courts, ignoring Congress, ignoring laws, gutting civil rights protections, stealing elections, handing our country's foreign policy over to the whims of authoritarian dictators—simply isn't possible.

And since it wasn't possible, nobody stopped them, mostly because those who were empowered to stop them didn't try. Why didn't they try? Because stopping supremacy for good—disabling the most recent expressions of supremacy: capitalism and deregulation and privatization, police and incarceration and imperial militarism—was seen as unpopular, and, because it was unpopular, it was impractical, and because it was impractical, it was impossible. And since it was deemed impossible, those who demand that we disable these latest instances of supremacy are seen as violent in a way that the horrific genocidal violence of supremacy are not; and reasonable practical people who claim to oppose supremacy scold those who demand that we actually end it, insisting that these anti-supremacy ideas are extreme, terrible, impractical, divisive, polarizing, and impossible, impossible, totally impossible.

And that's how movable sinks become immovable ones.

Another quick interruption to scroll quickly past before you continue the essay.

The Reframe is me, A.R. Moxon, an independent writer. Some readers voluntarily support my work with a paid subscription. They pay what they want—more than the nothing they have to pay. It really helps.

If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgements section of any future books.

I've spent a lot of space lately on criticism of leading centrist Democrats, which some have taken to mean that I'm missing the fact that it is the Republican Party which is disabling and dismantling the country right now in order to establish their dictatorial supremacist regime. So I'll explain: I focus on Democrats because I spent years cataloging Republican intentions, but now that they are in power, they are doing all the things that those of us who were paying attention knew they would, all the things that those who told us we were being polarizing insisted were impossible.

The Democrat are best positioned to oppose the Republicans, and are largely failing to do so, seeking instead to focus only on what is practical and possible, which they mostly define as not trying anything unless the success is assured—which, since nothing is assured), is a fantastic posture to take if you intend to not try anything. The time of warning and alarm is over; the threat is here, and the house is ablaze. Now is the time to talk about the response, which has been inadequate to completely absent. So I criticize Democrats.

I think the problem is that there is little desire within the party to move the immovable sink. And I'd observe that, if you don't want to move the immovable sink, you have to ignore the fact that your opponents are moving it already—because if they are moving it, then it isn't immovable, after all.

Senator-in-absentia Chuck Schumer, of whom I've been recently critical lately, took time from his busy schedule of not opposing the ongoing illegal Republican coup whatsoever to go on the teevee and explain to Chris Hayes that he is saving his energy for some future time if we enter a crisis, which he defined as being if Trump were to ignore the Supreme Court. Now, that phrase if we enter a crisis should be enough of a crime against observable reality to end Schumer's career for good and probably get him paddled in the public square with halibuts, but it's even worse: Schumer's named backstop against democracy is The Supreme Court, the very court that has been stuffed with bribed far-right apparatchiks who less than a year ago made the ruling that the president is allowed to break any law he likes. In Schumer's world, the president ignoring the lower courts while pushing anti-Constitutional segregation efforts is not a crisis, as long as the president doesn't ignore a Court that is very likely to tell the president that everything is A-OK regardless of the legality. Not only did Schumer downplay the current moment of almost unimaginable crisis, but he validated any eventual unlawful rulings of the Supreme Court, which has already invalidated itself, and left him with nowhere to go if it permits Trump's clear unlawfulness.

It all seems like Schumer is mostly looking for a reason to not move the sink.

And there's a recent push among the Democrats to abandon their focus on far-left policies—by which they mean trans rights and immigrant rights in particular—and start to pursue finding common ground between them and their opponents. This ignores entirely the fact that the Democrats have never in my lifetime run a left-focused national campaign (the closest they came was Barack Obama in 2008, which happens to be their biggest success), and they certainly didn't run one last time; they ran on ignoring Gaza and on making our lethal military even more lethal, and on protecting gun rights, and they toured with Liz and Dick Cheney, and so forth. But setting observable reality aside, their formulation also presupposes that there exists a constituency of voters that would oppose the oligarchy that is currently eating them alive, but which also lets their bigoted grievances and delusional fears govern their decisions to such a degree that they won't join an opposition to save their own lives unless those bigotries and fears are given first precedence. It's certainly true that there are many voters for whom bigoted grievances and delusional fears are a higher priority than their own survival, but, at the risk of pointing out the obvious yet again, such voters are going to vote primarily for their bigoted grievances and delusional fears, and nobody is going to be able to out-hate Republicans, nor should anybody try, nor would any victory achieved by doing so be worth calling a victory.

It all seems like a reason to not move the sink.

If Democrats really want to get the support of those holding bigoted grievances and delusional fears, they are going to have to focus on the ones who deem "not getting devoured by a fascist oligarchy" more important to them than their bigoted grievances and delusional fears. Again at the risk of stating the bloody obvious, for a demographic with those priorities, you don't have to abandon trans people or immigrants, because their first priority isn't their grievance and delusion, but not getting devoured. In fact, if we want to actually capture the support of such people then solidarity helps, not hinders, the effort. We're going to have to prove to anyone we'd want to join with us that we actually believe in opposing the fascist oligarchy that's devouring them. Can you imagine a worse way to persuade people that you will fight for them than agreeing to abandon your most vulnerable friends at the slightest provocation from the playground's meanest bully? I can't.

It strikes me just how failed this centrist posture is—failed from the start. Beginning the game with surrender. Starting negotiations with capitulation.

It doesn't seem practical. It seems impractical. It doesn't seem strategic. It seems like the abandonment of strategy. It won't move the sink, that's for sure.

Here's one last takeaway on the subject of sink-moving: People who stand for something have vision, and people with vision tend to capture people's imagination, even if that vision is hateful and abusive and unsustainable and disconnected from reality, as the supremacist vision is.

People who seek only to find the middle don't stand for anything. What is the middle? Nowhere, really. It's just a point between poles. Moving the poles is harder work, so those who seek ease ignore the poles entirely by deciding that poles are unmovable, and in so doing, they cede the whole battleground to those who actually care about something—good or evil. It's a morally and strategically vacuous position, utterly lacking in vision, and it won't capture anyone's imagination. Such empty and movable vessels may be useful if we actually succeed in moving the sink simply because they don't oppose anything, they'll flow smoothly into the new possible that has been defined for them, but they won't help anyone move anything until the work is already done.

So let's do what is strategic and practical and smart and realistic: Let's be movers of the immovable sink. Let's have a vision, and let's join with others who share that vision. Leave those without to their cramped view of what is possible, and let them do whatever marginal and cramped good they can do within the unnatural constraints they've placed on themselves.

Let's determine that we're going to grapple and grab and lift and heave and do whatever we can to move supremacy's sink. Let's determine we won't stop until it goes right out the window where it belongs, which probably means we won't ever stop, because centuries of brave and determined people moved it without ever seeing it out the window. While we have strength left, we'll drag it as far as we can. And maybe we'll get it out the window. If we keep believing it's possible, eventually somebody will.

Let's do it even if it's unpopular, even if it's divisive, even if it's dauting, even if it's impossible, because when the necessary thing is impossible, then constraining ourselves only to what is possible is not only immoral—it's impractical.

We might not be the ones who succeed, but we're going to try. We're going to do that much. And others will see us imagine that we can do the impossible, and start to imagine that they can do it, too, and someday, someday, they will be right about that.

Is success guaranteed? It never is when you actually stand for something. Success is guaranteed for people who only want to move to the middle of whatever other people have decided is possible. But we don't get to not try to move the unmovable sink. We owe that much to those who came before us. We owe that much to those who will come after.

Will it move? It might. But at least we tried, goddammit. At least we did that.

The Reframe is totally free, supported voluntarily by its readership.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any books I publish.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the essay collection Very Fine People. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He's always awake, always around, singing "ashes, ashes, all fall down."

Comments ()