Very Fine People

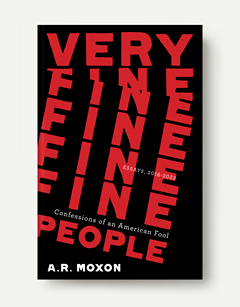

Excerpting the introduction to Very Fine People, which releases June 25 and is now available for presale wherever books are sold.

What follows is the introduction to Very Fine People: Confessions of an American Fool, which releases June 25 and is now available for presale wherever books are sold.

This is not the proclamation of an expert. This is the confession of a fool.

Maybe I should explain.

I wrote all the words you’ll find between these covers sometime between December 2016 and early 2023. Most were written after August 2017, which was a key date in my rapidly dawning awareness of the true nature of my country. August 2017 is when tiki-torch waving Nazis invaded Charlottesville, Virginia, in defense of treasonous confederate slaveholders and their own perceived supremacy. We know they were Nazis because they were chanting “Jews will not replace us,” and “blood and soil,” and all the other Nazi hits, and because they believed in Nazi causes and utilized Nazi symbology, and so on.

August 2017 was also when the White Christian president defended those who marched with the Nazis as “very fine people.” I call him “the White Christian president” because the people who support him are overwhelmingly understood to be a specific thing known as “white,” and overwhelmingly identify as a specific thing known as “Christian,” and the White Christian president made quite a show over the years of representing U.S. citizens exclusively based on whether or not they support him.

And, no doubt, there were white Christians who marched in the Nazi invasion of Charlottesville (titled “Unite the Right” by its organizers) and these were the “very fine people” toward whom the White Christian president gestured, to make the case that the pro-Confederate cause—which celebrates traitors who murdered their fellow citizens in order to preserve the institution of chattel slavery—shouldn’t have the rightness of their position questioned, simply because of the apparently coincidental direct allyship of overt Nazis.

And there were those who noticed that the White Christian president’s words amounted to a defense of the Nazis, and this act of noticing this observable and obvious truth offended his mostly white Christian supporters to no end. The presidential defenders drew a distinction they found important: he was very clearly not defending the Nazis who were there, he was defending all the other people there, who were not Nazis. The very fine people didn’t chant the Nazi slogans, I suppose; they just marched in the same crowd, and for the same basic cause. They must have heard the chants, but one must assume they had invented different reasons to march, and different causes. This was the distinction. We are meant to find this distinction meaningful.

But I knew better then, and I imagine you did, too. The White Christian president’s words were clearly meant as a defense of the Nazis, because the presence of the very fine people did what it always does whenever very fine people find common cause with Nazis. Nazis and Confederates and Christian nationalists and other authoritarian supremacists only ever rise on the permissive shoulders of masses of very fine people willing to lend their moral authority to a monstrous cause—yes, and their energy, too, and their normalcy and niceness and well-scrubbed politeness, and their deliberate unawareness as regards the methods and intentions of those with whom they march, and yes, their Christianity, too—because how could a religious person ever support atrocity if they did so out of a religious conviction? Their very fine presence in solidarity with monsters defends and enables the monstrousness.

I find myself thinking a lot about them—the very fine people.

They’re my people. I am somebody deemed “white.” I was raised Evangelical Christian. When the White Christian president made a show of representing white Christians exclusively, it is people exactly like me that he meant. In August 2017, the White Christian president, like all cheap hucksters, knew quite well which lies people would believe, knew quite well what lies his people wanted to hear, and knew quite well the lies they depended on for fortune and identity.

So he told the lie of the very fine people.

It’s a popular lie. It’s a traditional lie.

For most of my life, to one extent or another, I believed it.

And so I am a fool.

Once upon a time, and for most of my life, I believed in the very fine people of America—by which I mean I recognized that there were people who disagreed with me about politics, but I also believed that what most mattered was what we all had in common, without considering who was excluded when we said “we.” And it must be admitted, we’re all mostly very nice people. Meet us, you’ll see. Most are nicer than me, I’d say. Very capable. Friendly. Volunteer in our churches, many of us. Give to charity. Some of us form charities, and some of those charities do really wonderful things, whose effects can be shown on a flowchart. We mow our lawns. We pay our taxes. We work hard. We love our kids. If you have a flat tire on the side of the road, we’ll help you out. For example, take me. I am a pretty nice person, most of the time, and if I see you have a flat tire by the side of the road, I will be happy to hold the hub cap level and not spill the lug nuts while a more capable person than me actually helps you, while making vague affirming sounds and hoping you don’t notice my lack of basic mechanical ability. I want to be sure you know, in case you didn’t grow up among white Christian evangelical conservative Americans, as I did, that most of us aren’t pretending. We really are very nice, very kind, very generous. We are, by these and other measures, very fine people.

This made me think that fascism would be unpopular, particularly with people such as us.

It made me believe that white supremacy was defeated, specifically by people such as us.

And so I am a fool.

My parents were Christian missionaries, so I grew up in another country. It had been called the Belgian Congo for years and years. It was called Zaire when I was there. It is called the Democratic Republic of the Congo now. It was pillaged for a century by Belgians, and when the Belgians were kicked out, the people of Zaire elected a man named Patrice Lumumba, and the rumor was he had socialist leanings, which means that he wanted the wealth of the country he led to benefit the people in that country, and this made my country very uncomfortable, so we sent the CIA there to stage what David Robarge called in his 2014 paper CIA’s Covert Operations in the Congo, 1960–1968: Insights from Newly Declassified Documents, “a series of fast-paced, multifaceted covert action operations” which represented “the largest in the CIA’s history up until then” and “comprised activities dealing with regime change, political action, propaganda, [and] air and marine operations. . . .” And somewhere in there Lumumba was murdered by somebody for some reason, and was replaced somehow by a kleptocratic monster named Mobutu Sese Seko who did continue to pillage the country, but who did not have rumored socialist leanings, and who was not murdered by somebody for some reason. Perhaps it was coincidence that a rapacious dictatorial pillager of resources avoided a (rumored) socialist’s fate, and was not overthrown and tortured and killed like Lumumba. Instead of experiencing all that, Mobutu ruled for decades, as he robbed all the riches for himself and his country fell into further ruin, but remained, as Robarge puts it, “a reliable and staunchly anticommunist ally of Washington’s until his overthrow in 1997,” and so my country—which is the United States of America—was comfortable once again. Anyway, that’s where I grew up: in one of the most naturally rich and unnaturally impoverished places in the world. My father was a doctor. My mother is an educator and a nutritionist. They were there to try to make a dire situation somewhat less dire for the people nearby, and I think they and their colleagues did, and I’m glad about that, and it cost them a lot, and I’m less glad about that, but that is perhaps a story for another day.

When my family returned to the United States, the contrast in wealth and resources and infrastructure and ease and overall stability and available opportunity was stark. Somewhere in there my parents appear to have instilled in me some basic sense of the truth of the matter, but certainly most other available sources explained to me—both in words and in millions of silent assumptions—that this disparity existed not because a rapacious dictator had been placed in charge of Zaire through the self-serving actions of my country, but because we were uniquely blessed by God, and/or because our country is, was, and always has been The Greatest Country In The World. This made sense to me, by which I mean there was no real challenge to the narrative, and nothing much transpired as I grew up to shake my confidence in these received assumptions. My parents and my experiences did furnish me with a compelling sense that a society ought to care for those in need, and that all people deserved equal representation, and that inequalities in society ought to be corrected. And these weren’t controversial things to believe back then.

Yet there was still some room for disagreement. In my orbit were those who held that our society was already perfectly and unimprovably equal, and so anyone who now suffered, or experienced need or lack, did so not because of inequality, but only because of the regrettable but natural results of their own poor choices—and therefore any attempt to further improve our already perfected society represented unnecessary governmental overreach, and any attempt by the government to care for those in need represented dangerously destabilizing and unjust theft, and any talk of a collective duty to care for anyone who had been overlooked or to support the demands for justice of anyone who was still marginalized represented divisive and polarizing rhetoric. I debated these people, because I disagreed with this somewhat . . . but our political differences didn’t concern me much. We might argue, but we certainly wouldn’t think any worse about one another or assume bad intentions or a fouled moral compass, over what was really just a political difference. And anyway, though I could clearly see that some inequalities existed, I assumed they would be eventually and automatically corrected, like racism had been corrected, back in the far distant past—in the late 1960s, seven years before I was born, when the CIA was active in the Belgian Congo.

Some people were conservative. I was liberal.

Some people were Bulls fans. I was a Pistons fan.

Those were about equal values to me.

I spent the summer after my freshman year of college working for my mom’s co-worker’s husband, who owned and operated a roofing business. This meant I mostly worked with my mom’s co-worker’s husband’s brother, whose name might have been Tim, so let’s call him “Tim.” Every day, Tim listened to that famous rodeo clown of the airwaves, Rush Limbaugh, who had been gifted with a big bellicose voice that commanded attention, and who used that gift to call feminists Nazis, and Hillary Clinton a baby-eater, and Clinton’s 12-year old daughter an ugly dog. Rush—who we eventually learned was a drug addict—liked to proclaim that drug addicts were all criminals who should be punished severely, and that impoverished people were all lazy and should be punished severely, and that people who believed that it was a society’s responsibility to care for those in need were all fools who hated America and wanted to destroy it, because they were evil people who wanted evil things and could not bear the sight of goodness. Every day Rush treated us to these and other comedy bits, and he was paid millions and millions of dollars for using his gift that way, and so the hours passed easily on various rooftops around my hometown. I thought Rush was nuts and his jokes were cruel, but I also considered him mostly harmless, because who would actually take such a person seriously? Maybe Tim thought that way, too. We never talked about Rush or the things Rush said. Tim sure did want to listen, though, and I sensed it was going to be easier and more comfortable to just listen along than to argue with Tim about Rush, so that’s what I did. I assume Tim kept listening in the years after that summer I spent roofing. It’s not clear to me when people stopped laughing at Rush and just started nodding, or if they were all nodding from the beginning, because I wasn’t paying attention, and all the people I knew were very fine people, and we were the greatest country in the world, and I had faith in that.

This faith was shaken in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, as I watched our frightened country get lied into a disastrous and criminal multipronged opportunistic war, and I couldn’t help but wonder at how effortlessly so many of us were able to metabolize the steady flow of damning information about the lies that had fueled those wars, how seamlessly they welded the contradictory available information onto their previous belief structures, leaving their support for the damned liars at our nation’s steering wheel completely unaffected. I had to wonder how it was that they hadn’t noticed certain things that were becoming unignorable even to coddled little me about the bigotries in our country and how many people clearly supported them, and about the way inequalities did their harm whether or not you supported them or even acknowledged them. And I had to wonder at how many fringe bigots were positioning themselves as Republican and Evangelical Christian leaders, and were met with—if they were met with anything at all—only the politest of remonstrations, the merest ‘ahem’ bookended by calls for unity in the church despite our political differences. I began to suspect the day was coming when the Republican Party, and the Christian church that supported it, who had for so long played wink-and nod politics with authoritarianism and white nationalism, would find that their ability to play both sides against the middle was no longer tenable, that they would be forced, by the preferences of the very voting base they had been cultivating, to run somebody who was an open white supremacist and fascist.

I was right about that.

I also saw very clearly that this would at last be a bridge too far for all my very fine people. I was certain that they would finally see the truth of what they had supported, would finally turn away, that the Republican Party would be lost in the wilderness for an age, until it was finally willing, after decades of pushing an anti-human worldview, to change and grow and rejoin humanity.

I was wrong about that.

The white supremacist arrived, and he couldn’t have been a bigger cartoon farce: Donald Biggestbest Trump himself, rodeo clown of all rodeo clowns, a man you wouldn’t trust to feed a soft-serve ice cream cone to a stray badger, much less lead a country. And the very fine people—my very fine people—went for him. I watched some of them posture at opposing him—an opposition that mostly focused on their discomfort with his grotesque tone and crude behavior—but that was in the early days, when they still thought, as I did, that the idea of such a man actually becoming president was preposterous. As soon as it became clear that he was indeed to be the Republican standard-bearer, I watched them each, one by one, with only a handful of exceptions, drop their diaphanous hankies of performative opposition and stand before all of us exposed, proudly wearing their new emperor’s clothes, willingly bowing before their gobby golden calf. Willingly? Enthusiastically. It was a growing enthusiasm. It was almost as if people who had been waiting for permission to embrace authoritarianism had finally been given it. I watched as the white evangelical Christian church in the United States—the tradition that raised me—revealed itself as the enthusiastic, sustaining, energetic, rapturous force powering a successful, openly white supremacist, authoritarian, fascist political movement, led by a pig of a man, an incurious narcissistic fool without a single redeeming quality. And I watched, as those within that religious tradition who were uncomfortable with this reality set themselves to the work of keeping comfortable relationship with those who had embraced fascism, even if it came at the expense of their relationship with those who were menaced by it.

This was the rapidly dawning horror for me as 2015 bled into 2016: the understanding that this—this—was not only what my very fine people were willing to go along with, it’s what they had wanted all along. This was the anointed one they’d been waiting for, the pain messiah they’d finally summoned to hurt the people they wanted to see hurt, to control the people they believed it was their natural right to control, and to protect themselves from their growing fear that they and their comfort would no longer be treated by American power as supreme. The answer to the question “what outrages against humanity will white evangelical Christians in the United States tolerate?” proved the same as the answer to the question “what proofs of its own inhumanity will white Christians in the United States look the other way to avoid knowing?”—which is to say, anything and everything. What I learned was this: the moment of falling away won’t ever come, not because very fine people don’t see the disastrous and unsustainable course we’ve set, but because they perceive some advantage within it for themselves, and so have decided to decide that the course is good.

Not just good, but goodness.

Not just right, but righteousness.

Not just a way of living, but “our way of living”—a phrase in which the most interesting word to ponder is “our.”

What is our meaning when we say our?

Who do we mean when we say we?

We sure don’t mean everyone.

And then Trump won the election, and my already-crumbling world broke. I sat that night in the dark, watching the results come in, not knowing what to do, feeling menaced and nauseous, and understanding that a lot of people were feeling far more menaced than me; because unlike me, they had never been considered we; because unlike me, they were going to be under an even more direct and targeted threat, now and for the foreseeable future. The overwhelming thought I had was this: “A lot of people are going to suffer and die because of this, and the people who voted for this know it, and knowing it makes them feel happy and safe.” And also came the inescapable gnawing recognition that this had always been the case, and it was only now, with this shock to my comfortable system, that I was finally seeing it.

And I was right about that.

That election night, I didn’t know what to do. Eventually, I began to do what I could. You bring what gifts you have to the moments you find yourself in. If I am anything, I am a writer. My skill, humble though it may be, is to present ideas that other people already know but cannot name, using language that names it for them. I’m told this is encouraging, to know that somebody else feels that way too, and helpful, enabling a more constructive way to think about those ideas. Sometimes I’m not bad at doing this, so that is what I did, and I published some of it online, where it found an audience. You’ll find some of it in here, a bit cleaned up from the original publication, along with some previously unpublished additions.

More specifically, here’s what you’ll find between these covers:

In the months after the 2016 election, while still reeling from the permanent demolition of the reality I’d known, and the betrayal of every fine principle I’d thought our nation represented by institutions and people I’d thought trustworthy—I wrote an essay called Sky. It was my lament. It ended with as much hope as I could muster, along with a call to my fellow very fine people, a call to those who I had believed were better than they had proved themselves to be. It was a call to work to prove that they could be as good as they insisted they already were. Six years later, that invitation is still open, but it has to be admitted that we have collectively proved ourselves to be even worse—more gleeful in ignorance and cruelty, more toxic in intent, more destructive in action, far more willing to construct vast moats of unawareness between ourselves and the inconveniences of caring about other human beings—than even the most jaded newly awakened fool would have dared believe.

Near the end of the first year, in 2017, I posted a series of essays called Bubbles, naming what I perceived to be the terrible lies our nation has been founded upon and concluding with what I perceived as our role in the world, which is to live as good stories, as works of art. And I still believe this today . . . though after witnessing the response of our institutional structures to the atrocities of the ensuing years, I wonder what else might be required of us, if we are to defend human art from those who seek to destroy it.

More recently, I wrote a series called Streets. It was begun in the year before the 2020 election, continued through that election and the violent (and still ongoing) attempt to overturn it, and finished while the outcome of that election was still in hazard, in the aftermath of a still-impending insurrection, with Trump out of office but at his liberty, his party entirely in his thrall, his fascist vision being pushed with all tools at their disposal. It was my attempt to answer the question how did we get here?

Most recently of all, I published a series of essays in my weekly newsletter, The Reframe, which represent most closely where I am now. I’m collecting them here in an edited and restructured form, in a series called Spirit. They’re about where we’ve arrived, and how we got here, and where I think we should go from here if we’re interested in survival as a nation and a species—an open question, I realize. It’s my attempt to answer the question what do we do now?

The things printed between these covers are things I’ve learned recently, but they aren’t things recently true. Only my awareness is new. Maybe yours is, too. There are others who’ve known all these things, and more besides, for a long time. How long? Their whole lives. They’ve been telling us about it all along, and we haven’t heard until recently. I have to conclude we haven’t wanted to know.

We? I.

I haven’t heard until recently. I have to conclude I haven’t wanted to know.

These things were always obvious to many people in this country.

So please remember, this is a fool’s confession.

If you’re one who has been wise to these matters your whole life, I hope my words honor your experiences, and I sincerely apologize for all the ways they will fail. This book represents my progressing awareness, my ongoing attempt to contend with the country I’d failed to see, and figure out what sort of person I want to become, as I reconstruct myself and my shattered worldview. Perhaps you will find my progression interesting, too, in the manner of watching a baby deer learn to walk.

And if you’re a fool like me, still reeling even years later from new knowledge of old truths long known, my hope is that this will help you. My hope is that my story is familiar, and that these essays will put words to your story, and that having words to put to your story will help you tell it. My hope is to demonstrate how my frame has moved over the years and put words to my slow discovery—about what is broken, and how repair might occur, and what sort of person to try to become in the aftermath of painful new awareness—and then to give an idea of how we might create unlikely but necessary change, how the frame might be moved for others, too, for more and more, in our nation and in our world.

So here goes.

Preorder information for Very Fine People.

The Reframe is supported financially by about 5% of readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the upcoming essay collection Very Fine People, available for preorder now. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He set the controls for the heart of the sun.

Comments ()