How Did We Get Here?

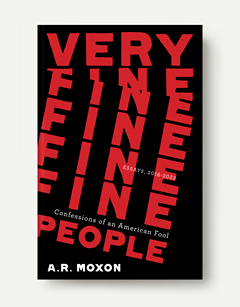

Excerpting a chapter of Very Fine People, which releases June 25, and is now available for presale wherever books are sold. The book ponders three questions. This is the first one.

What follows is the first chapter of Part 2 of Very Fine People: Confessions of an American Fool, which releases on June 25 and is now available for presale wherever books are sold.

As a contextual preface, Part 1 is called "Bubbles," and defines the sickness of the United States as a spiritual sickness—in other words a sickness of collective consciousness, or culture, or belief. It names what I believe to be a great truth, which is that every human being as a unique and irreplaceable work of art carrying an intrinsic and unsurpassable worth. Then it names the spirit that has captured so many of us—which negates that great truth, which desires genocide and slavery—by identifying the foundational lies that energize it: first that we human beings bear no relation to one another; next, that life must be earned by generating profit; and, finally, that failing to earn life is an inherent crime best redeemed by violences of neglect and abuse and brutality.

This line of thinking led me to ponder three questions.

This essay introduces the first question.

OCTOBER 2020

Three years ago, I wrote about our foundational lies, and concluded that our frame was wrong, that the answer to the bad stories we’d been telling ourselves was to tell a better story—to be a better story.

It was a good answer. Not very practical, but uplifting for sure. Very positive. I still believe it’s true.

It’s not good enough.

It’s not wrong, but it leaves me somewhat stranded, like I’m hanging from a branch on the side of a mountain, and being advised that my problem is that I am in a bad place, and the answer is to climb to a better place. OK. Great. Thanks! Climb to a better place how? Be a better story how? What story?

Three years ago, I also concluded that you don’t move frameworks of belief by changing minds through debate, but by changing spirit through stories.

I still believe that, too.

So, let me tell you two stories.

Story one: let’s pretend, for the sake of argument, that there’s a virus.

Let’s pretend it’s deadly. Let’s say it’s a novel new strain of an old structure that we’ve known about for a long time. In this story, the virus appears quickly, and it spreads quickly, and rapidly becomes a global pandemic. It harms a lot of people, and many of those it harms, it kills. In some places, people are better prepared for a virus, and fewer people get infected, and fewer people die as a result. In other places, people are less prepared for a virus, and more people get infected, and more people die.

Let’s imagine that one reason this virus spreads so effectively is because a large number of people who get it are asymptomatic. Unaffected, they transmit it freely. They aren’t in danger themselves, but they’ll put other people in danger if they don’t take the trouble to become aware. Some people will be harmed, and some will suffer permanent damage, and some will die, because of these asymptomatic super-spreaders, who will never even know that they were the cause.

Next, let’s pretend it’s discovered that the best way of containing such a virus is for everybody to agree, for the sake of those who are most vulnerable, to do some things that are inconvenient. Let’s make up some random examples. . . . Let’s say they’d need to wear something slightly uncomfortable on their faces, and avoid travel and social contact as much as possible at times of high infection, and perhaps spread out during necessary human interactions. Maybe they’d need to get a vaccine and then boost it every so often, perhaps annually. And let’s say that the best way of defeating such a virus was for governments to invest heavily: providing meaningful and sustained financial relief for people whose livelihoods had been compromised either by the spread of the virus or by the measures needed to prevent the spread, and also providing a vigorous, nationally coordinated testing and tracing regime led by expert epidemiologists to learn as much as possible about the virus, and then spending whatever it costs to combat it.

We might dare hope that in time the virus in our story would be defeated. The virus would then seem, for all intents and purposes, to be gone. It wouldn’t be gone, of course, but it would be contained, like smallpox is, like measles used to be. So even though the virus would seem to be gone, it would invariably, if we didn’t stay mindful of it, come back in ways that would affect us all once again—because viruses mutate, grow, change, and eventually evolve into new strains.

I hope this totally hypothetical scenario isn’t too divorced from everyone’s recent experiences to be relatable.

In this story, any society that was wise and knowledgeable would invest in vigilant systems to monitor and guard against outbreaks—would commit, in other words, to knowing as much as possible about viruses in general, and then on spending what it costs to combat and contain them. Let’s pretend that, in our story, some countries decide to do exactly this. But, in our story, there’s a particular country that, though it has more resources than any other, decides instead to ignore the virus. Can you imagine this? A society containing millions of people who absolutely refuse to participate in the minor discomforts needed to contain the virus, who oppose the remedy on the basis of cost, or who choose ignorance about remedy rather than remedy itself? Can you imagine millions of people, all framing their decision about a systemic virus exclusively along lines of personal individual risk and intention and freedom, demanding proofs of things already known, then refusing the proofs when they are given? Verbally (sometimes even physically) attacking anyone who dares ask them to honor minimal social considerations and observe basic practices of public health? Try. Stretch your imaginations and pretend that there were people who became very angry even when confronted with the sight of other people engaging in the minor inconveniences that would contain a deadly virus.

Let’s pretend that in this society there exists a well-funded corporate media infrastructure fully committed to validating the choices of these deliberately ignorant people, and increasing their ignorance by broadcasting further disinformation, false equivalencies, and outright lies. Imagine such an apparatus, wearing the trappings of authority and trustworthiness, but aligned to delivering to their viewers reinforcements of their ignorance, fully dedicated to framing that ignorance as wisdom, and urging their audiences toward increasingly extreme and aggressive acts in defense of that ignorance. Before long you might decide that such a society was committed, as a first priority, to ignorance of things already known, in order to satisfy the temporary indulgence of their own convenience. Before long you might even have to conclude such people had aligned themselves with the spread of the virus, no matter their stated intents. In our story, these people didn’t align themselves with the spread of the virus primarily by actively and deliberately spreading it. They aligned themselves with it by simply refusing to know things that are already known, because they didn’t want to accept the responsibility that came with knowledge, because they were intent on avoiding any inconvenience that might come with that responsibility.

Or, try this: Imagine a government that decided only to fight the virus to the extent that corporate profit was protected, and, outside of those bounds, would simply exercise a practiced ignorance that the virus existed, or else claim the virus had been contained and now was over, or that it was simply a new part of the immutable unchangeable way things now were. Imagine the leader of such a government who decided to suppress testing, because the report of infection was politically damaging.

Imagine a government that decided to not invest in monitoring or guarding against the next virus, that even dismantled existing apparatuses and safeguards in order to save a relative pittance. Before long, you might decide that such a government was not committed to the health of its citizens. Before long, you’d have to conclude that such a government had deliberately chosen ignorance of things already known, in order to satisfy the temporary benefit of other interests. Before long one might even have to conclude such a government had aligned itself with the spread of the virus, no matter its stated intents. Members of the government would say that they were against viruses—of course. But any perceptive observer would know better. In our story, this government didn’t align itself with the spread of the virus by actively spreading it. It aligned itself by simply refusing to acknowledge things that were already known, because it didn’t want to accept the responsibility that came with knowledge, because it was intent on avoiding any cost that might come with that responsibility.

End of story one.

Story two: let’s pretend there’s a disease called “cancer,” and that there’s a person who has it. Let’s say it’s been growing in this person’s body, stealthy and invisible, for long months and years. Let’s say it’s only made certain localized parts of the body less comfortable as it grew—twinges and aches that in retrospect might have been considered warnings to heed. Now let’s say that for the first time there is an unignorable visible sign; a tumor grown so large it distends the belly. Let’s imagine a doctor who runs some tests. She prescribes immediate surgery to remove all affected tissue, an aggressive campaign of medication and treatment, frequent testing, and a radical change to diet, exercise, and environment.

Now: Let’s imagine a patient who ignores all symptoms and refuses all the tests. You’d have to assume that—for whatever reason—they don’t want to know the frightening truth. Right?

Or imagine our patient refuses the treatment, because in their estimation the treatment is too radical. You’d have to assume the patient had decided, for whatever reason, that the treatment was no longer worth the pain or the cost; that they’d decided instead (as some do, as they progress to end-of-life care) to let matters progress on the established course, with all the fatal consequences that choice entails.

Correct?

But now imagine our patient accepts the initial surgery, but refuses the lifestyle changes. You’d have to assume they’d decided that the likelihood of a recurrence wasn’t worth the effort to prevent it, or that the decrease of enjoyment in their life wasn’t worth a decreased likelihood of recurrence of a deadly condition.

Yes?

But . . . imagine our patient makes these decisions without facing the reality of what those decisions mean, refuses all diagnosis and treatment and measures meant to prevent recurrence, not from a difficult-but-clear decision that the fight is not worth the pain of treatment or the cost of change, but because they imagine—despite any evidence—that the fight can be won without any cost. Imagine our patient insists that diet and environment don’t affect risk factors for recurrence of cancer, or insists that their body isn’t a system—that what’s happening in one organ in the abdomen can’t possibly affect any other part of the body. Imagine our patient decides, despite all available evidence and the exhortations of multiple oncologists, that the tumor is the only problem, that the cancer from which it grew doesn’t exist, that the clearly proven environmental factors that fostered it are actually unproven. Imagine our patient makes their only priority a return to the familiar comfort of their life exactly as it was before they received the knowledge of the diagnosis, and expects health to be the result.

Before long, you’d have to understand our patient as somebody committed, as a first priority, to not knowing things that are already known, in order to try to return to a previous state that is no longer attainable. Before long, you’d understand that our patient is putting their entire body in grave danger, not because they’ve made a measured, aware, and purposeful decision about their physical being, but simply because they don’t want to acknowledge the reality in which they now find themselves. Before long, you’d have to conclude that this patient is aligned with the spread of the cancer, whether or not they claim that as their intent.

Our patient in this story doesn’t align themselves with the spread of the cancer by actively spreading it. They align themselves with it by simply deciding to not know things that are already known, and by not taking active steps to oppose it.

Or, try this: Imagine our patient exists within a healthcare system that makes their ability to pay for treatment and prevention a higher priority than the treatment and prevention itself. Imagine this system commands doctors and hospitals to refuse to allow the tests or treatments, unless that first priority can be satisfied. Imagine a healthcare system that lets people die if treating them isn’t profitable, and which commits itself to maximizing those profits. Imagine a system structured so that the patient having an already-existing sickness—a pre-existing condition—actually makes it less likely for that person to receive health care.

Before long you’d understand that such a system was not committed to health as a first priority. Before long you’d have to conclude that such a system had deliberately chosen ignorance of things already known, in order to satisfy the temporary benefit of other interests. Before long you might even have to conclude such a system had aligned itself with cancer and every other type of disease, no matter the intents of well-meaning people within such a system who diligently and earnestly labored for, and often achieved, the healing and health of others. Those who control and defend such a system will tell you that they are against cancers—of course they are. But any perceptive observer will understand their deeper intentions. Such a system doesn’t align itself with the spread of cancer by actively spreading it, but simply by refusing to acknowledge things that are already known, because it doesn’t want to accept the responsibility that comes with knowledge, because it is intent on avoiding any cost that might come with that responsibility, and on reaping the benefits that come from the existence of the problem.

End of story two.

It seems to me that viruses and cancers have a number of clear similarities and intersections. Both are opportunistic, both committed only to their own growth. Both are systemic, in that what they consume are healthy systems—first destabilizing them, and then, if left untreated, compromising them to the point of failure. Both ought to be prevented and treated no matter the cost, if the patient desires treatment. Surely we all agree on that point, right?

Right?

In both cases, effective treatment involves: first, knowledge that they exist; then a short-term change—often radical, often targeted—to eliminate the threat; then a remedy—a permanent, holistic, watchful, strategic, systemic restructuring of priorities and behaviors—to monitor for and prevent recurrence. In both cases, aligning against the spread requires active, persistent, determined, informed, and transformative action. In both cases, aligning with the spread requires only passivity, which will prevent the needed transformative action.

Virus and cancer: all either needs to devour a healthy system is for you do nothing.

They’ll do the rest.

The differences between viruses and cancers are also instructive.

A deadly virus has no place whatsoever in a healthy system. A virus spreads by mutating a new form for which a healthy system has not yet developed a defense. The treatment for such a virus is systemic eradication. The ongoing remedy against a virus involves monitoring for new strains to detect them, containing them as they’re detected, and eliminating them once contained. A perfectly healthy system will contain zero deadly viruses.

A cancer typically grows when a system improperly prioritizes a part of itself that would otherwise be healthy and natural: bone, breast, lymph, lung, liver. Treatment for a cancer is meant to, hopefully, restore the tissue to a right balance within the system, removing the cells committed to an unhealthy growth while saving the cells that the system requires to function properly. After treatment for liver cancer, for example, a person in remission will still have some part of a liver, just one that (hopefully) remains free of cancer. And, though liver cancer springs from the liver, the existence of liver cancer doesn’t mean that livers in general are bad, and the suggestion that somebody working to eradicate liver cancer is in some way anti-liver would be a foolish notion indeed.

With a virus, the challenge is keeping it out of the system entirely. You defeat the viral attack on the body’s systems, then keep vigilant against the next mutation, because if you don’t, it will grow, and spread, infecting more and more, taxing our response systems, and making us more vulnerable, especially those of us who were vulnerable already, including those of us with . . . cancer. With a cancer, the challenge itself is systemic. The ongoing remedy for a cancer often involves testing and monitoring not just of the affected area, but of the entire system, to ensure all of it is working in a way that is healthy and sustainable. A tumor is often merely the most unignorable symptom of a systemic vulnerability, demanding radical changes to the configuration of body and lifestyle. In many cases, in order to preserve the body, things cannot go on as they have previously, because to return to such a state makes disaster inevitable, and failing to make radical changes compromises the entire body, making it susceptible both to recurrence of tumors and even external factors, like . . . viruses.

When we find our systems compromised by either cancer or virus, we should not avoid radical and transformative change, if we would align with health. We should seek radical remedy and transformational change. We should desire them as if they were survival itself—which they are. And, if we would align against recurrence, we should never avoid a systemic restructuring, no matter the expense. We should seek it. We should desire it as if it were survival itself—which it is. If we care about health, we must never refuse to know what we know. The cost of ignorance is, eventually, everything. The cost of knowledge, however painful, can never exceed it.

So now that we have that out of the way, it’s time to talk about the United States and the world.

These days, talking about the United States and the world means talking about the person who is currently, as I write this, the Republican White Christian president of the United States, who actually is—and I still cannot believe I am saying this—Donald Trump.

So: he’s a liar.

So: he’s a fascist.

So: he’s an authoritarian.

So, he’s using his office to enrich the businesses he still owns and from which he still profits. So, he encourages and celebrates police violence, and advocates the use of military force against peaceful protest. So, he’s using the exact language and phrases of white supremacy and neo-Nazis and fascists, and pursuing their exact desired policies. So, he’s deliberately demolishing all norms and standards of a functional democracy, in service of demolishing democracy, in service of himself. So, he’s working to put himself entirely above the law, and, even more, positioning himself as the law, as someone whose authority must not be questioned, to whom loyalty is irreducible from patriotism, for whom criticism must be understood as not just criticism of the country but as an attack on it. So, he used the power of his office transactionally, first to try to destabilize the coming elections, then to try to punish political enemies by imposing medical sanctions on his own citizens during a pandemic—premeditated manslaughter at best, genocide at worst.

Also: His entire party has rallied around these efforts in support of them—almost as if somebody doing what he is doing was their plan all along. Also: his followers, his true believers, millions and millions strong, all cheer for him, and the worse he gets, the more that he perfectly embodies all of the worst things any of us warned he might become, the more they seem to love him. They cheer and cheer and cheer, and they tell us to get over it, and they say “fuck your feelings,” and then they tell us they love the way he makes us weep, because they love to drink our tears. And they take to the streets and government buildings with massacre weapons to win back their never-lost right to honor a murderous movement to preserve chattel slavery, or to establish their right to spread a virus to the satisfaction of their own convenience. And they laugh and laugh and cheer and cheer and yet they never seem to get happy. They cheer for a system that is optimized for the abuse of the marginalized by the powerful, not because they are powerful, but because seeing the abuse of those more marginalized than them comforts them that they are not so marginalized as that.

Also: comfortable masses, tens of million strong, seem not to worry about any of this, as long as it doesn’t touch them personally. If you think this list of quite-obvious truths seems hysterical, overwrought, scolding, divisive . . . then be even more comforted than you have already made yourself! You have a lot of company. You speak the language of comfortable masses, for whom the report of abuse is seen as the real abuse, who save their ears for the resentments of the attackers, not the screams of their victims—because the screams of the victims carry a moral duty to respond, while the attackers ask only for an easy silence. I know this, because, if I’m honest with myself, I know it’s a silence I’ve given many times before—and so, if you are a comfortable person, have you. Still, there are those among us who are now, in this rough authoritarian age, coming to these inescapable realizations of truths which are only new to us. The tumor at last distends the belly, and now we know.

Also: there are those of us—not white enough, wealthy enough, male enough, abled enough, cis enough, straight enough—for whom this is no revelation, because this authoritarian abusive country is the only one we’ve known.

So. Here we are. And the question is: what next?

Next? Well, either he wins, or he loses. Either he gets what he wants, and his party gets what they want, and his cheering hordes get what they want, or else they don’t.

If he wins, it’s a grim matter but at least it’s a simple matter. We have enough of a trendline to see exactly where we’re headed. We’ll see the full-throttle victory of all our old worst historical traditions and the death of all our best aspirational dreams for ourselves. We’ll see the final death rattle of whatever shreds remain of our tattered global reputation, and the irrevocable end of our oldest alliances. We’ll fully commit to being an authoritarian kleptocracy, a theocratic genocidal white ethno-state. There will be some semblance of something they’ll call “elections.” There will be some semblance of something they’ll call “the news.” There will be something they call “the law.” And many things we already see will be escalated: troops whose ostensible purpose is to protect our borders, ranging far from the border; other troops called “police” whose ostensible purpose is to protect our citizens, occupying neighborhoods full of citizens, all of them acting as they see fit to create the sort of general and specific terrors that comprise their true missions; locations that will be called something less overt than “concentration camps”; people dying on the street because they no longer have what’s needed to survive in a country that has been architected in such a way to digest and destroy unprofitable people.

Yes, I think that’s what they’ll do. If not, why are they already doing it more and more, as much as they’re able, as quickly as they’re able, everywhere they’re able? It’s not comfortable to know, but those not knowing it reveal a willful effort to not know things already known.

And if he and his party lose? If we actually manage to temporarily halt their advance?

That’s a somewhat more hopeful matter, but not so simple. Because we’ve learned things about ourselves, and our country, and our friends and neighbors, and our systems of administration and authority, that we can never un-know. We now know who will look the other way, and what they’ll look the other way for. We know who will find reasons to accept unacceptable things, or become confused about obvious truths and obvious lies. We know now what people will stand for. We know now what people will cheer for. When the chips are down, you find out what people are like when the chips are down. And then you know.

We’ve watched the message of an openly fascist, openly corrupt, openly white supremacist president grow, and spread, a new strain of an old virus against which we’d stopped being vigilant, mutated for a world of international television and internet media, a sensationalized version of our country’s oldest sins. We’ve heard those who would cheer this spiritual infection of hate, who would gather in red-capped throngs to spread this soul-rot between each other. We’ve seen the enthusiasm of some—the eagerness, even the joy—at the thought that they might once again become great; that in a nation that was beginning to tentatively seek redemption, they might consider themselves already absolved; that in a nation that was listening to more and more voices, they might become the only voice once more; that in a nation that was seeking diversity, they might once again become not just the default consideration but the only one; that in a nation that was imperfectly seeking equality, they might again become the sole priority. We’ve seen the quick acclimation of others to this new reality, as they opened themselves to this new infection of old lies, seeking some advantage they might press, as the most vulnerable populations first felt the effects. We’ve heard all the excuses they give themselves for all this. And we’ve heard all the threats they’ve offered, the retribution they’ve promised to deliver, if they don’t get their way. We’ve seen the sunglasses-hat-goatee warriors on the steps of government buildings toting their privately owned massacre weapons, and we’ve noticed that our police show far more deference to them than to others who present far less threat to a peaceful order, whose cause is justice rather than supremacy. We’ve seen the cops rioting, brutalizing crowds every night with military equipment and thuggish tactics, for the crime of challenging their state-sanctioned license to murder with impunity. They aren’t going to stop cheering for it, even if voters depose their beloved hate goblin. They’re not going to stop expecting it, or demanding it, or fighting for it. They’ve seen the white supremacist authoritarian anti-democratic state that Donald Trump would bring, and they very much want it. They think it’s great.

But there’s more.

We now know that, even though Trump is a disruption to the status quo in some ways, he isn’t only a disruption to the status quo. In many ways, he is a part of that status quo’s inevitable progression. He’s the result you can expect to see, in a society which believes that we have no shared society beyond individual desire, that life must be earned, that profit is how you earn it, and that violence redeems. We can see that Trump isn’t a disruption to business as usual, but rather a purified concentrate of that business. In other words, even though he spread a virus, Trump isn’t a virus. He’s the first unignorable tumor—for those of us comfortable enough to have ignored the previous symptoms. Yes, he’ll have to be removed completely, but afterward things are going to have to be different. If they aren’t, then we’ll find ourselves here again.

And we may well find ourselves here again.

Even many opposed to the spiritual virus of MAGA America aren’t interested in quarantining it, or vaccinating against it. Some still remain opposed to radical transformations of our ways of living. Some want only to remove the tumor of Trump, then return to the exact situation that allowed it to grow. We’ve heard all the justifications for this, because we know them. We often are them. These complacent masses aren’t strangers, any more than the cheering red-capped throngs are strangers. For many of us—probably most of us—they’re the people we grew up with and live around. They’re us. Happy, smiling, friendly, many of them. They love their kids. They go to church. They work hard. They pay their taxes. They walk their dogs. They love us, some of them. Yes, and we love them, many of them—and if we seem so angry, perhaps the reason is that the anger we feel toward these friends and family and neighbors, while appropriate and honest, is easier than the deep sorrow and mourning, that those we love would so willingly, eagerly, or complacently align with a man who has no redeeming characteristics, align with a spirit that pursues atrocity, energizes hate, demolishes democracy, and promotes an empty promise of tawdry glory that’s as chintzy and false and ignorant as everything else about its grotesque leader. We share our lives with these people, whether they (or we) will admit it or not. We share families and neighborhoods and associations and workplaces and nations.

I see two questions we have to face, in the teeth of this new knowledge. These questions sound simple, but aren’t. They will be the same questions after the election as before, no matter the result—and so will the answers.

I’ll get to the second question eventually.

The first question is about awakening, conviction, and confession.

It’s this: How did we get here?

I’ll tell you how I think we got here.

I think we drove, on streets we built.

Preorder information for Very Fine People.

The Reframe is supported financially by about 5% of readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the upcoming essay collection Very Fine People, available for preorder now. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. When he's on the street (depending on the street), I bet he would definitely be in the top 3 good lookin' girls on the street (depending on the street).

Comments ()