What Do We Do Now?

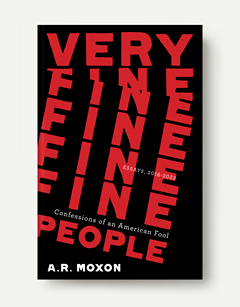

Excerpting a chapter of Very Fine People, which releases June 25, and is now available for presale wherever books are sold. The book ponders three questions. This is the second one.

This is an excerpt from Very Fine People: Confessions of an American Fool, which releases on June 25 and is now available for presale wherever books are sold.

Very Fine People ponders three questions.

The first question was "how did we get here?"

This excerpt introduces the second question.

(December 2020)

He lost—that shit of the world. The pig president. White Evangelical Christianity’s bronzed calf. He lost.

That’s good.

The person who beat him was a man named Joe.

Joe seems like a nice enough fella, I guess. He’s a pretty conservative guy if you go by the way most people in the world track such leanings. I’m not particularly conservative, so this means I disagree with him about most things, but he loves his family—his wife, his kids, even his dogs—or at least he knows how to act like it, and to make displays of empathy, by which I mean he seems to understand that other people exist, and seems to understand why that might matter. He has decades of relevant experience in public service—which includes many horrible errors, but even the errors are at least relevant to the job—and he appears to take the job seriously. He speaks in mostly complete sentences, although he is admittedly not the strongest available candidate in that area, but the things he says mostly align with observable reality, and are mostly centered on matters of consequence rather than the latest demands of his own ego. He probably won’t encourage mobs of armed fascists, in or out of uniform, to attack citizens or politicians, for example. These are all novelties these days, when it comes to presidents.

Joe will be a better president than his predecessor, in the same way that a casserole will make a better meal than a festering mountain of turkey shit. The point being: I don’t even have to tell you what kind of casserole. However, this is not the same as saying “Joe will be a good president.” That matter is still up in the air, and would probably require defining what we mean by good.

During his campaign, Joe faced a blistering range of attacks from his opponents, all of which amounted to the sentiment “if this man gets into office, he will enact radical transformative systemic changes to the way things are, all of which are extremely obvious and needed solutions to enormous and present problems that threaten all of our lives.” And Joe won by promising repeatedly that he wouldn’t do most of those absolutely necessary things, or at least he won while promising not to do them. Meanwhile his opponents are still terrified that he will do all these awesome and desperately necessary things he’s promised not to do and seems to have no intention of doing. Joe’s opponents are convinced without evidence that Joe is controlled by “woke” activists—“woke” meaning people who are aware of the systemic problems we face, and “activists” meaning people who insist that because solutions are desperately needed, we should organize to enact them as soon as possible, with or without the permission of those in power. I’m told this means that “woke activists” are dangerous fanatics and foolish children. I’m told this by “the adults in the room,” by which I mean people who know better than the rest of us, and can explain in great detail why improvement and repair and solutions aren’t practical or possible or even desirable. The adults in the room live in “the real world,” which is the world exactly as it is, to which no changes can be made, and within which nothing can be done about anything, and they know exactly why it’s important to never even talk about trying, because if we did talk about trying (they’ll explain) then the people who already have spent years calling Joe a socialist might call him a socialist.

A “socialist,” by the way, is somebody who thinks that society exists, and that governments should work for the health and thriving of human beings, and that this means that some things that are conducive to the public good are good in and of themselves even if they don’t create profit for industry, and therefore many such things—like education, or art, or the judicial process, or medical care, or transportation—should be public goods provided by and for the public, administered by representatives chosen by the public, rather than profit centers run specifically and exclusively to turn a profit. They also believe that profit engines should be regulated, to prevent them from making decisions that would maximize profits but also harm human beings. So that’s what a socialist is, and it’s one of the most horrible awful things a person can be, and if you don’t believe me, just go to the real world and ask one of the adults in the room about it.

Joe was chosen by the adults in the room to lead us specifically because he promised to not be a socialist. As I mentioned, Joe’s opponents all already called him a socialist anyway, and they really seem to believe that he is one, but the adults in the room seem to think that it would be even worse if Joe was called a socialist while actually being one, because this might lose him the political support of people who have already shown an unshakeable determination to never support him, ever, no matter what. To Joe’s credit, he seems to really mean it when he says he isn’t a socialist, so I hope all the adults in the room can be reassured for a minute, that Joe will keep seeking the support of people who will never support Joe. The adults in the room could use the chance to relax, I think. I’ve noticed that they’re a rather panicky crowd, endlessly nervous that somebody might actually suggest a transformative and impactful solution to an enormous and pressing problem.

Anyway.

Maybe Joe’s opponents are right, and Joe will stop listening to the adults in the room, and start listening to all these socialists—these dangerous fanatics and foolish children—and finally do all these desperately needed things that amount to repairing what is broken, and demolishing systems and structures that profit from brokenness.

We can hope.

The adults in the room have many other recommendations. There’s a lot of talk now about healing, which seems to be centered on healing the people who aren’t wounded—the ones who did the harming, the ones who would like to do a lot more harming, who talk eagerly of their plans to harm. There’s a lot of talk now about unifying, without much talk about what we would unify around, or what we would hope to accomplish once unified. There’s a lot of talk about compromise, without much discussion about what—or who, because it’s always who—we would abandon in order to secure this compromise, or what we expect to gain by it, or what Republicans have ever given up in compromise. (That crowd hasn’t even conceded the election yet, by the way, and doesn’t seem likely to.) There’s a lot of talk about how those who want to demolish our democracy and abuse millions of our friends and neighbors aren’t our enemy—as if that’s something a person gets to choose about people who are actively and enthusiastically attacking them or their loved ones.

And all the people who cheered Trump on, who now refuse to acknowledge that any of the depredations of the past four years ever actually happened, who have already determined not to even recognize Joe’s authority, are ready and eager to cheer for the next fascist white supremacist demagogue, or maybe just for the same one again, because a fascist white supremacist demagogue is what they very clearly want. And the adults in the room are already encouraging us to bring these authoritarians back into the very fold the authoritarians are actively trying to destroy—not because the intentions of authoritarians have changed, but because doing so would make things feel normal again, and comfortable, at least for a while. For a lot of people, it truly seems as if all of this has basically just been a parlor game, in which they didn’t ever feel the stakes, for which this was mostly about their personal discomfort with the uncomfortable realizations being forced upon them by Trump’s grotesquerie. For a lot of people, it seems like the point of the game is to return to a state before our national diagnosis, when some of us could still pretend to not know just how sick we are.

There is, it seems, a desire to not know things already known. I suspect this is because if you know that something needs to be fixed, then you face a choice, which is whether or not to fix it—and if you decide to fix something that needs fixing, then you have to do the work of fixing it, and then you have to pay the price of repair.

There is, it seems, a desire to not do this work or pay this price. This is understandable. Treatment of deadly disease is frightening and disruptive, often radical and targeted in the short term, usually followed by a permanent, holistic, watchful, strategic, systemic restructuring of the way things used to be—to monitor for and prevent recurrence. Radical and transformative treatment is a lot to take on. People tend to not want disruption and discomfort, so comfortable people oppose transformative change. I get it.

However, we all know how sickness works. “Recurrence” is something that happens, for example, if you don’t do the work to prevent it.

It’s worth wondering: what comes after Joe?

If we don’t engage in necessary radical systemic treatment, then I think what comes after Joe is recurrence of the disease, mutation of the virus. So, I think what’s needed is radical and transformative change, if we would align ourselves with health. We should actively seek radical remedy and transformational change. We should desire these things as if they were survival itself—which they are. And we’re going to have to do it without the support of people who have aligned themselves with our national diseases, which are the status quo, the way things are.

We have a lot of work left to do.

It’s not clear we are willing to do it.

We know things about ourselves that we hate to know, but there’s no going back. There are two questions we have to face, now that we have this knowledge. I chose to wait until after the 2020 election to raise the second question, because while the election mattered a great deal, it mostly determined how much damage and harm and pain and theft and murder there was going to be in the near term; but this outcome doesn’t mean there won’t be any, because the winning coalition seeks to maintain our present system, and these outcomes are what our present system generates. And these questions, which sound simple, but aren’t, are the same after the election as they were before, as are the answers.

The first question was about conviction and confession.

It was how did we get here?

The second question is about repentance and reparation.

Here’s the second question: What do we do now?

The Reframe is a reader-supported publication with a pay-what-you-want subscription structure. Free or paid, everyone gets the same newsletter. If you would like to support my work, and if you can afford to, please consider upgrading to paid.

(October 2021)

Sometimes answers are stubborn.

I’ve been staring at that question for almost a year now: What do we do now?

Joe’s answer to that question was simple: We return to business as usual, that’s what we do now. Trump was the virus, that's the idea. Defeat the virus, and the system will return to normal, and all Joe’s Republican friends will go back to behaving the way they did back in the 1970s and 1980s, back when maleness and whiteness didn’t feel so threatened, and open white supremacists and progressives all found it much easier to work together to get things done. That was Joe’s pitch, and it won him the election, and he was wrong.

They didn’t go back to those earlier comfortable times. Quite the opposite, in fact. The year since the election has proved beyond doubt that the white supremacist christofascist viral mutation of old foundational lies that the Republican Party released into our national bloodstream has no intention of stopping just because one major symptom has been displaced as our national leader for the present; it’s also proved that our systems, which are optimized to preserve an increasingly untenable status quo, have no mechanism to address it.

As a result, we are expected to tolerate a growing list of intolerable things.

I’ve seen hordes of enraged white supremacists invading the Capitol, sent by a sitting president in a nearly successful attempt to overturn an election and murder Congress, abetted materially and legislatively by a Republican Party that has spent all its time since that day working to ensure that the plot remains unexamined and that the next one will be successful and enduring. I’ve seen Republican governors engaged in a persistent targeted strategy of sabotage against all efforts to contain the Covid pandemic as the death toll mounts and mounts, abetted by a powerful and popular network of propaganda platforms, which day and night issue rhetoric and policy propositions that are increasingly indistinguishable from that of white supremacist and Nazi groups such as the ones who invaded Charlottesville in 2017. I’ve seen a stolen Supreme Court work diligently with gerrymandered state legislatures to kick over the load-bearing pillars of equality and modern society. I’ve seen marginalized people targeted for harassment and harm in increasingly open terms, and with increasingly undisguised intention.

There are gun massacres most weeks. Most days, really.

Why? I’m told the answer is complex, and probably so. I’ve noticed that guns are a common factor to all of them. It seems to me we have so many massacres because people who want to enact gun massacres are very easily able to get massacre weapons—by which I mean guns made for the clear purpose of massacring people. It is very easy to get massacre weapons; certainly, it’s far easier for someone to get one than it is to buy or rent a house, or get affordable medical care, or a college education. And it’s easy to buy massacre weapons because Republicans refuse to make it difficult to buy massacre weapons, and in fact insist on making it easier and easier, and even brag about doing so, and pose in Christmas cards with their scrubbed pink families all brandishing massacre weapons like some weird pajamas-based cult. They say they do this because they believe that individuals should have the right to use massacre weapons in “self-defense” however they wish to define the term, which really seems inseparable from saying that individuals should have the right to massacre at their discretion—particularly since no matter how many individuals use massacre weapons to murder people, Republicans never stop defending massacre weapons and people’s rights to have them without any restriction. And they seem to believe this mostly because they are paid to believe this by a powerful lobby that makes more profit with every massacre, but also because the people they represent believe that they have the right to kill at their own discretion, and greatly resent anyone who questions their judgment and their right to decide who lives and who dies, or to own weapons designed to murder people as quickly as possible, and to own as many of them as they want. They’ll tell you that they might need to kill somebody someday, or maybe a bunch of somebodies, and if they aren’t able to do that whenever that day comes, they’ll tell you, that would be the worst form of tyranny imaginable to them. I’d say we have massacres because we are a society optimized for massacre, and we know we’re a society optimized for massacre because disturbed people who want to enact massacres are being accommodated, and the rest of us, who do not want a society optimized for massacre, are not. When the city decides, what is meant by the city is not most of us, it seems, but only those people who would like to have a world of gun massacres. We have massacres because the people who get to decide such things would rather have a world with massacres than one without. And we know this, because a nation of plentiful gun massacres is what we have.

Also, Democratic leadership appears to have decided that the answer to these massacres, which are not in any way prevented by police in our overpoliced country, is to give the police more money. And they appear to have decided that the solution to systemic police brutality is to give the police more money. I’m just waiting to hear that they’ve decided that the answer to the baby formula shortage (I forgot to mention: there is a baby formula shortage) is to give the police more money—because if there’s one group that needs more funding, oh baby, you’d better believe it is the police, who use civil asset forfeiture to steal more from citizens than any criminal group steals each year, who take so much, and give back so little, and who have convinced themselves they have such a dangerous job they must spend every single moment of it making sure that they are safe even if it means that everyone else is not. They have such an important but dangerous job (unless you look at the actual statistics, in which case you’ll see that, no) that they have been assured by our Supreme Court that they cannot face any accountability from anybody for anything they do, provided they establish that they were frightened when they did it, and the legalese for this is “qualified immunity,” a term that boils down to, “if a cop wants immunity, they qualify.” And the Supreme Court even ruled that if you’re a border agent within 100 miles of a border, you’re not accountable even to the Constitution for any reason, and you don’t even have to say you were scared—you’re just an unrestricted enforcer of whatever the fuck you want to say the law is, and if you want to say the law is you, so much the better.

So much for the Constitution.

All these people doing this are allowed to keep doing this. They insist on being treated as if they and their actions are normal, and, as they are treated that way by a cowed opposition and a sleeping media, they have become normal. The people we elected to fix this can’t fix it, I’m told. Their hands are tied, I’m told. Apparently stopping the people who are breaking the rules would be against the rules. The people who are allowed to decide about stopping them don’t want to stop them, and the people who want to stop them aren’t allowed to decide. The Senate Parliamentarian said so. If you don’t know who that is, I’ll tell you; we learned recently that apparently they are the most powerful person in the world whenever and only whenever everyone whose job it is to do something would rather do nothing and needs somebody to tell them they can’t do anything, at which point the parliamentarian shakes their head sadly “no” and everyone else throws up their hands in what they hope is believable frustration.

None of this is popular, yet all of it seems inevitable. Most people want solutions, yet solutions never materialize, even though we quite often know what the solutions are, or at least in what direction they’re located. Still, even the hope of solutions seems distant.

The root problem appears to be that we can’t get the people who want problems to give us permission to fix the problems, and we can’t get the people who claim to want to fix the problems to stop asking those people for permission.

And there are other things, too, but they all seem to boil down to this issue: We can’t fix what’s broken, because the people who want things broken appear to be in charge of deciding whether or not broken things get fixed.

So, we have our prognosis.

It’s not just a virus that we refuse to fight. It’s a cancer that we refuse to treat.

So, I’ve spent a year staring at the question: What do we do now?

My answer is: we realign ourselves to oppose the unjust configurations of our natural human system . . . and then I delete that phrase, and try again, because at a certain point these things get lost in abstraction.

Change our spirit? Yes.

Change the atmosphere? Yes. Great. Wonderful.

How?

My focus is usually on spirit, and rarely on specific action. I think it’s more effective to think about what sort of person to be than what sort of thing to do. This frustrates people. Yes but what actions do you propose? What is your specific plan? What are the five steps to do that? This frustration is understandable. Actions are something more direct than simply pointing in the direction we ought to go and insisting we can get there. Actions are often measurable. They feel productive. However, I still tend to focus less on specific action and more on spirit.

I have reasons.

Often I simply don’t know what to do. I’m still confused and broken. My worldview has been shattered and I’m reconstructing it, so all I’m able to do is share what I’ve learned, and expound on what I observe. And I’m not particularly knowledgeable. When you’re a writer who can arrange thoughts in an effective way, there’s a great danger that people will start thinking you know something, and then they start looking to you for answers. I’m sympathetic. It’s tough to be a disappointment, but probably not as tough as being disappointed.

But also, I worry about making global pronouncements about specific actions. Specific actions are specific, and thus not all specific actions are appropriate or feasible for all people, while spirit is more generally applicable. You’re you. You have a specific situation and specific skills and resources and privileges and specific intersections with our unjust and corrupt systems. What you need to do depends on all those things. So what should you do?

Good question: What should you do?

Maybe you should run for office, but maybe you know you’d be bad at that.

Maybe you are best at spreading awareness to the confused, or maybe finding the right words isn’t your thing.

Maybe you need to call your representatives every day, or maybe you are just trying to keep your head above water and don’t have the time for that.

Maybe you need to march. Maybe you need to shout. Maybe you need to make your voice silent so others can be heard. Maybe you need to stay nonviolent. Maybe you need to join a fight. Maybe you have a lot of money and you need to give to bail funds and mutual aid networks and activist organizations. Maybe you have influence and power and prestige, and you need to use them to confront injustice, or maybe you need to give up your outsized influence so others can have a larger share of it. Or maybe you just need to finally give a shit, rather than to decide that the safer thing is to find a reason to be apathetic or cynical—two states which people of bad intent would most prefer for you. Maybe you are in a compromised position under active threat from toxic bullies and you just need to keep yourself safe and alive. Or maybe someday you’ll surprise yourself, and discover you need to take extreme unlawful action to keep people under active threat alive. I doubt Miep Gies expected to become a lawbreaker, for example, but when she hid the Frank family, that is what she was. I doubt she imagined she’d build a secret room in her house in defiance of a genocidal police state. I think in an age that was guided by a spirit of murderous order, she was guided by a spirit of truth and hope—truth that every human being carries an intrinsic value more important even than order or law; hope that things can get better. She asked herself “what should I do?” and then did it, and so did Harriet Tubman, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and many other lawbreakers as well.

What do you need to do? I’d say first realign yourself against what is broken. Become the kind of person that acts in a fierce spirit of love, and then be guided by that spirit. Actions are specific, and can change a situation. They’re necessary, but they’re situational. Spirit is atmospheric, and can change the world. So, I focus on changing the atmosphere, the spirit.

We must realign. We must change our national spirit.

I type the phrase, then delete it. It’s not wrong, but it frustrates me.

Realign. Change our national spirit. Yes. Great. Perfect.

How?

Eventually we do have to get to practicalities. The compass and the navigation aren’t of much use without the journey. So, finally, I’m going to propose some actions. To name these actions, I’m borrowing several terms from the tradition I grew up in, which is Christianity—American Evangelical Christianity, to be precise. These actions are focused on the work of alignment, which is a work that each person must perform inwardly on themselves before they can hope to direct it outwardly.

The terms I’m using are: awaken, convict, confess, repent, repair, and redeem.

Here are the actions I propose:

1. Awaken to the truth of systemic corruption and abuse, in all its ugliness.

2. Convict ourselves to the truth that we share responsibility, to transform our minds.

3. Confess our individual and shared involvement, publicly and unequivocally.

4. Repent from that involvement, by agreeing to pay the cost of repair.

5. Repair what is broken, by actually paying that cost and doing the work.

6. Redeem our natural human system, by entering the cycle of the realigning work of repair.

These steps are the work of repair.

They are a process—a progressive and realigning sequence.

They are, incidentally, exactly how we fix . . . streets.

Configuring streets—updating existing ones, building new ones—requires work.

If we wish to maintain our streets, or extend them, or modify them, or build new ones to serve new needs, we would have to . . . do it. Obvious, right?

But some time before we do it, we’ll have to realize that there’s a need to do it. An awakening. And some time after that, but still before we do it, we’ll have to accept that doing it is our shared responsibility. A conviction. And some time after that, but still before we do it, we’ll have to determine to actually do it, and make the necessary plans. A confession. And some time after that, but still before we do it, we’ll have to agree to pay what it costs, and modify our priorities toward that end. A repentance. And some time after that, the work will have to done. And before, during and after that, the full cost—in labor, in inconvenience and disruption, in actual money—will actually have to be paid. The repair.

This is the work of configuration, of alignment, necessary to any repair or maintenance.

The cost is practical. It’s also spiritual.

It’s spiritual work. It’s also practical work.

It’s a process—a generative, sustainable, progressive and realigning sequence.

I think that means it’s also redeeming work.

We use these steps to realign our streets. We could use them to realign ourselves—our individual choice to realign against our current inherited dominant popular supremacist societal configuration of injustice and abuse.

If enough of us realign ourselves, we’d create a new spirit. Change the atmosphere. Reset the compass. Tell a new story. Whatever metaphor you like.

This would be more than just thinking I’m against injustice. It would involve doing the realigning work and paying the disruptive cost. That would be hard—for some of us more than others. But if we did it, the spirit would change.

That’s what I think, anyway.

I’ve been staring at the second question for almost a year now: What do we do now?

I think I’m finally ready to answer.

What do we do now?

We fix our fucking streets, that’s what we do.

Preorder information for Very Fine People.

The Reframe is supported financially by about 5% of readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the upcoming essay collection Very Fine People, available for preorder now. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He may ask himself: how did he get here?

Comments ()